Inflation and disinflation: What role for fiscal policy?

The upsurge in inflation since 2021—the sharpest in more than three decades—has called on policymakers to respond.

Government policies need to be informed by an understanding of how inflation affects various groups in society through uneven impacts on the budgets of different households.

This chapter examines the multifaceted impact of inflation on fiscal variables (see infographic) and the distribution of well-being and it explores how fiscal policy can do its part to curb inflation, while supporting the vulnerable.

Governments influence how the costs of inflation are distributed not only through discretionary intervention but also through automatic indexation of pensions, transfers to poorer households via social safety nets, wages of civil servants and tax thresholds.

A survey of current international practices shows that indexation varies considerably across countries.

Pensions are the most commonly indexed—in nearly all advanced economies and about 40 per cent of emerging market and developing economies—followed by cash transfers to vulnerable groups and public wages.

The impact of inflation on the fiscal accounts also depends on redistribution—in this case, between the public and the private sectors. Unexpected inflation erodes the real of government debt, with bondholders taking the brunt of the hit.

For countries with debt exceeding 50 per cent of GDP, each one percentage point surprise increase in inflation is estimated to reduce public debt by 0.6 percentage point of GDP, with the effect lasting over the medium-term.

These effects are smaller or negligible for countries with a large share of debt denominated in foreign currency.

When inflation is expected, it is not associated with a decline in debt ratios, highlighting that inflating debt away is neither a desirable nor a sustainable strategy.

Likewise, deficit-to-GDP ratios initially decline as the nominal (current monetary) values of the economy’s output increase and, consequently, the tax base rises, generating more tax revenue, while spending fails to keep up.

But such effects dissipate over time. In addition, the chapter shows that redistributive effects of inflation on households are more complex than usually thought.

Based on surveys of thousands of households in Colombia, Finland, France, Kenya, Mexico and Senegal, estimates are provided for the price acceleration from the second quarter of 2021 to the second quarter of 2022 for three channels (1) real incomes (wages and pensions), (2) losses in net nominal assets and (3) faster-than-average price rises for the main goods and services consumed by a given group (such as food prices, which hurt the poor during the period studied).

Results show that changes in real income were the most important and differed the most across countries but less so across income groups.

Losses on net nominal assets were larger for older groups than for young adults (who often have outstanding mortgage debt) in countries with sizable household credit markets.

During the period considered, the estimated impact of inflation on the poverty rate (prior to new policy measures in response) is about one percentage point in three countries in the sample (France, Mexico, Senegal).

Fiscal policy also influences aggregate demand and inflation, with its ultimate impact depending on the monetary authorities’ response.

Estimates indicate that an increase in public spending of one percentage point of GDP led to an increase in inflation of 0.8 percentage point in the 1950–85 period and of 0.5 percentage point thereafter.

The difference arguably stems from a more forceful response by central banks to rising inflationary pressure in the post-1985 era.

Analysis using a model that embeds inequality in incomes, consumption and asset holdings shows that a reduction in the fiscal deficit leads to a similar level of disinflation but requires a smaller increase in interest rates than when central banks act alone.

The analysis also shows that deficit reduction combined with transfers to the poorest yields a smaller drop in total private consumption and a consumption path associated with less inequality across households.

These effects are even more important when public debt is high because fiscal restraint limits the rise in the cost of borrowing and reduces debt vulnerabilities.

On the path to policy normalisation

As the global economy recovered from COVID-19 related disruptions and as exceptional measures by governments largely came to an end, fiscal policy moved to a tightening stance in 2021–22 amid high inflation and the need to reduce debt vulnerabilities.

Nearly three-quarters of economies tightened both fiscal and monetary policy in 2022 up from a quarter in 2021 . With signs of easing inflationary pressures, the global economy is now entering a new phase .

The effects of policy tightening will weigh on economic activity.

Governments will need to manage high debt against a backdrop of modest growth and less favourable financing conditions in the medium-term .

Between 2021–22, global public debt declined to about 92 per cent of GDP—reversing half of the record increase in 2020—because of the economic rebound following the COVID-19 crisis, inflation surprises and the end of exceptional fiscal support measures enacted during the pandemic.

The pace of fiscal retrenchment and decline in debt varied from one country to another, depending on how fast they exited the pandemic and how subsequent shocks affected them.

In emerging markets and low-income developing countries, which have lower levels of domestic currency debt, inflation surprises provided less relief for public debt ratios.

The near-term fiscal outlook remains complex and risks are firmly to the downside with significant uncertainty surrounding the growth outlook and rapidly changing financial conditions (April 2023).

The pace of fiscal tightening is projected to slow in 2023 as economies face spending pressures.

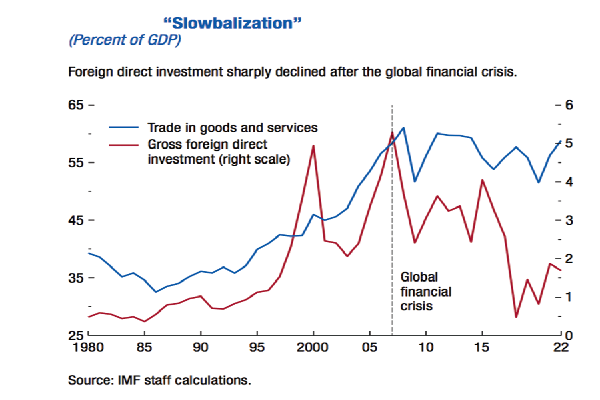

Ongoing geopolitical tensions may lead to further increases in defence spending and fiscal support to address negative effects from disruptions to international trade.

Industrial policies, including government subsidies, may also emerge to foster import substitution.

Progress on reducing global poverty stalled in 2022, with about seven per cent of the world’s population now projected to be in extreme poverty in 2030, which will fall far short of the goal of eradicating extreme poverty.

Low-income developing countries, many of which are in or near debt distress or have limited fiscal space, face a particularly difficult balancing act. Many developing countries are grappling with tighter budgetary constraints.

Low and stagnant levels of revenue have also hampered progress in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals and food insecurity has even reversed the progress made in combatting hunger prior to the pandemic.

Governments will need to continue to balance their efforts between rebuilding fiscal buffers, supporting disinflation and protecting the most vulnerable amid considerable uncertainty about future economic growth as the global economy adjusts after massive shocks.

In the event that inflation turns out to be stickier than expected, further monetary tightening will be needed and will weigh on economic activity.

Downside growth risks could also be magnified if financial sector instabilities intensify and increase stress on public finances, as governments may be called to support the private sector.

Global growth could also be adversely impacted by a faltering in China’s recovery and an escalation of Russia’s war in Ukraine, which could renew tensions in energy markets and exacerbate food insecurity in low-income countries.

Over the medium-term, under current policies, public debt is expected to rise to close to the record levels seen at the height of the pandemic.

Its path will depend crucially on the pace of economic growth and whether borrowing costs, which remain elevated in emerging market economies.

Conclusion

Amid the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine, investment growth is expected to remain modest and below the average growth rate of the past two decades.

This trend is not specific to the region but widespread across Emerging Markets and Developing Economies (EMDEs).8 Empirical analysis suggests that the deceleration of investment growth could be associated with downswings in economic activity, terms-of-trade deterioration, weak real credit growth, and stalled investment in climate reforms.

Slower growth of investment in the region is holding back long-term growth of potential output and per capita income, as well as progress on meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Way forward

Amid substantial financing needs, limited fiscal space and rising borrowing costs, policy makers in the region will be required to improve the efficiency of spending.

Scaling up investment will require additional financing from the private sector and the international community, accelerating reforms to improve the institutions that support private sector growth, developing local capital markets, improving the quantity and quality of public infrastructure, enhancing the efficiency of utilities and strengthening domestic resource mobilisation.