On the two occasions I have met the Vice-President, Prof. Naana Jane Opoku Agyemang, long before she probably conceived the idea that she would one day be the Number Two of this republic, she came across as a pleasant, rather friendly and gracious lady.

Whilst I was understandably not in favour of her becoming Vice-President by reason of my strong NPP persuasion, I was happy for her when she eventually assumed that high office, particularly as the first woman to do so.

Eerie familiarity

Like many Ghanaians, I felt a sense of concern when news broke the other day that Madam Vice-President had reportedly been taken ill and, based on medical advice, had been asked to seek further treatment abroad.

Of course, her VVIP status meant this development was bound to be a front-page story.

But then beyond that, it sounded eerily familiar and sent public commentary into a frenzied tailspin.

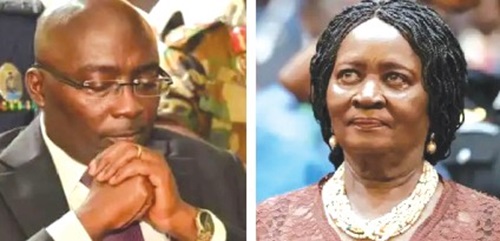

Back in January 2018, the then sitting vice president, Dr Bawumia, took medical leave and flew to the United Kingdom for medical treatment when he was taken ill.

Armageddon literally descended, with palpable outrage in some quarters, that whilst the elite fed off our taxes in obtaining the best of care from elsewhere, back home, the rest of us were thrown at the mercy of a rather ramshackle health system.

Extreme partisanship

Of course, Dr Bawumia’s medical leave was not the ‘Ground Zero’ in this vexed matter. In the past, the deaths of several high-ranking politicians in foreign hospitals where they were seeking medical treatment have always generated public outrage over the state of our health system.

But perhaps the illnesses of two successive Vice-Presidents from different sides of the political divide, followed by trips abroad for medical care, bring to sharp focus the extreme partisanship that appears to colour any sensible debate about ensuring a health system that functions effectively for the benefit of its citizens.

Following the news about the Vice-President and the ensuing commentary, my good friend Kwame Sarpong Asiedu, a UK-based pharmacist and Fellow of the Centre for Democratic Development (CDD) Ghana, captured many thoughts on the matter most succinctly in a Facebook post thus;

“It is disheartening to see how extreme partisanship continues to overshadow meaningful conversation.”

“There are those who, just a few years ago, passionately defended the medical trips of a former Vice-President, but today see this as karma and vindication of their position.”

“Likewise, there are those who were outraged when a former Vice-President sought treatment abroad, but now attempt to silence journalists and well-meaning citizens who dare to ask valid questions.”

“This hypocrisy is part of why nothing ever changes.

We reduce life-and-death issues to political football, shifting our stance depending on who is in power rather than standing on principle.”

“We must remind ourselves that health has no political colour.

When the system fails, it fails us all—NPP, NDC, and the politically neutral alike.

Until we begin to demand better, not for political points, but for national progress, we will keep repeating this cycle.”

Truer words were never spoken.

Reality check

It would be churlish and utterly naïve to suggest that all of us should access the same health care.

I would, for instance, be most scandalised to see the President of the republic in a queue at the Mamprobi Polyclinic seeking treatment for malaria, all in the name of egalitarianism.

No country does that and I do not know anyone who would suggest or insist on that.

Reality check is key. Even the defunct Soviet Union, at the apogee of its communist ideology, had special clinics for elite members of its politburo that slammed the door in the face of its ‘ordinary’ citizens.

However, here is the rub. The ‘ordinary’ citizen who can only seek treatment at the Mamprobi Polyclinic or any of the public healthcare institutions should be assured of a system that is able to provide sufficient care that assures his dignity as a citizen.

When a health system routinely features women lying on the floor in crowded hospitals to give birth, with their dignity thrown out to the dogs, when patients have to go through hell to get even the most basic of care from rickety public hospitals or clinics that are almost akin to death traps, then it understandably rubs citizens the wrong way when the political elite are ferried abroad to receive specialist care when they are unwell.

From that flows loud howls of indignation, even if many of these howls are politically lopsided.

Truce?

Decent, quality health care should not be a privilege for a select few; it should be a fundamental right guaranteed by a system that is robust, well-resourced and capable of meeting the needs of all citizens—not just in rhetoric but in practice.

With a sitting NPP Vice-President and a sitting NDC Vice-President both having fallen ill in office and having been transported abroad, it appears there has been an equalisation in respect of both outrage and sturdy defence by both sides.

Hopefully, this ‘draw’ will usher in a truce of sorts and drive the conversation towards real, urgent reforms and investments to give every citizen of this country at least a good shot at decent healthcare delivery.

Admittedly, both sides have made efforts to improve healthcare delivery, but clearly far more needs to be done, and urgently so.

I pray for the Vice President’s full recovery, just as I did for Dr Bawumia back in 2018.

The reality is that as the rather sudden deaths of President Mills and Mr. P V Obeng taught us, in some cases there may not even be enough time to ferry one abroad for treatment.

Rodney Nkrumah-Boateng.

E-mail: rodboat@yahoo.com