Ayine writes on Supreme Court's explanation on why Special Prosecutor's Office cannot be equated to public service

The Supreme Court on Wednesday, May 13, 2020 held that Mr Martin A.B.K. Amidu is eligible to be the Special Prosecutor because his office cannot be equated to the public service which is caught by the retirement age of 60 as prescribed under Articles 190, 195 and 199 of the 1992 Constitution.

In a 5-2 majority decision, the court held that the Office of the Special Prosecutor (OSP) is similar to that of Article 70 of the 1992 Constitution office holders.

Article 70 office holders include the Chairperson of the Electoral Commission, the Commissioner, Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice and the Chairperson of the National Commission for Civic Education.

“We conclude emphatically by stating that the category of public officers to which the Special Prosecutor has the closest affinity is Article 70 office holders whose conditions of service, including retirement age, are pegged to that of the Justices of the Court of Appeal.” [70 years].

“Parliament in prescribing the mode of appointment of the Special Prosecutor and Deputy different from Article 195 (1) did not flout the constitution,” the court held.

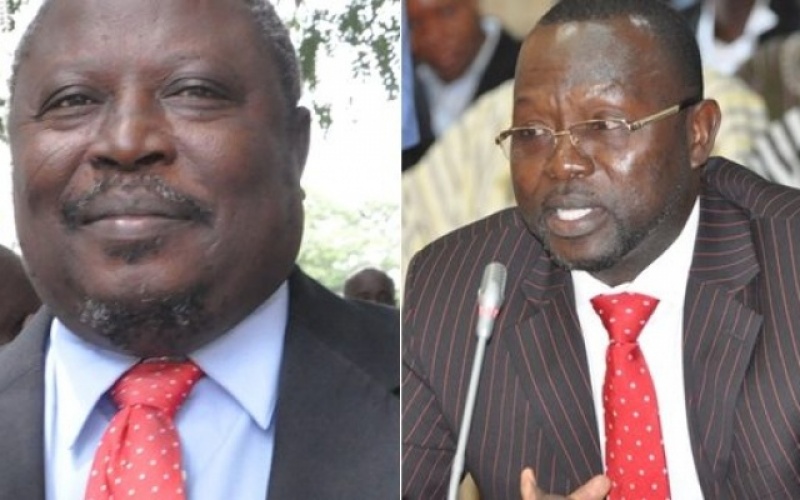

The decision of the court follows a suit filed by Dr Dominic Akuritinga Ayine, a former Deputy Attorney-General, who argued that Mr Amidu was ineligible to be the Special Prosecutor because he was 66 at the time of his appointment and, therefore, his appointment was unconstitutional.

It’s constitutional

Per its decision, the apex court has declared as constitutional Section 13 (5) of the Office of the Special Prosecutor Act, 2017 (Act 959) which equates the conditions of service of the OSP as the same as Article 70 office holders.

The only difference is that Section 13 (5) of Act 959 makes the tenure of the Special Prosecutor a seven–year non-renewable term, while Article 70 office holders retire at the age of 70.

The majority decision was read by Justice Nene Amegatcher who was supported by the Chief Justice, Justice Kwasi Anin Yeboah, and Justices Paul Baffoe-Bonnie, Samuel K. Marful-Sau, and Professor Nii Ashie Kotey.

Justices Nasiru Sule Gbadegbe and Agnes Dordzie dissented.

- Related:

- Supreme Court explains why Special Prosecutor's Office cannot be equated to public service

- Supreme Court okays Martin Amidu's appointment as Special Prosecutor

Dr Dominic Ayine, after the court made its full ruling public has subsequently reacted.

Below is a copy of what Dr Ayine wrote.

I have read the judgment of the Supreme Court in the case I brought challenging the constitutionality of the appointment of Hon. Martin Amidu as the Special Prosecutor on grounds of age.

For those who have either not followed the case or read the judgment as issued by the Supreme Court, the issue before the Court was whether a 66-year old person can be offered an appointment in the Public Services of Ghana?

And posed this question to the Supreme Court because our Constitution, the fundamental law of the land, provides for a mandatory retirement age of 60 years and the possibility of a post-retirement contract for a maximum period of 5 years.

In other words, a person retiring from the a Public Service Office created under the Chapter of the Constitution dealing with the Public Services of Ghana, may be offered and can accept an appointment to continue to serve for a maximum period of 5 years after retirement and thereafter the Constitution is silent.

I will be writing a more extensive analysis of the extremely disappointing judgment of the Court in a later installment on this page.

However, the judgment of the majority of the Court, by Amegatcher JSC, purported to rely on the case of Yovuyibor v. Attorney-General [1993-94] 2 GLR 343 as authority for the decision, especially as it related to the categories of employees in the public services.

In particular, the majority relied on the dicta of Amua-Sekyi JSC in that case regarding the classification of employees in the public service.

I must say with all due respect to their Lordships that, the dicta of Amua-Sekyi in relation to the classes of employees in the public services, were at best obita dicta as they had no direct bearing on the issue that was before the Court in that case.

The issue was whether Police officers who attained the retiring age of 55 two weeks upon the coming into force of the Constitution in 1992, were entitled to the enhanced retirement age of 60 under article 199 clause 1 of the Constitution or should be made to retire at age 55 under the then Police Service Act, 1970 (Act 350).

The Supreme Court upheld their case for an enhanced retirement age of 60 years and declared the provision of the Police Service Act, 1970 (Act 350) null and void and of no effect as it contravened article 199(1) of the Constitution, 1992.

As I have sated above, I will be writing a more extensive piece on the judgment but for now I wish to leave you with the words of Ampiah JSC in his concurring judgment:

"The Police Service is part of the public services of Ghana-- vide article 190(1) of the Constitution, 1992. Members of the service are therefore public officers.

In so far as the Constitution, 1992, the supreme law of the land, provides that "a public officer shall, except as otherwise provided in this Constitution, retire from the public service on attaining the age of sixty years (vide article 199(1) of the Constitution, 1992), and there being no other provision in the Constitution, 1992 and section 8(1) and (2) of the transitional provisions of the Constitution, 1992 to my mind not being relevant to the particulars of this case, any law which states to the contrary is inconsistent with the Constitution, 1992.

Consequently, to the extent of the inconsistency, the Police Service Act, 1970 (Act 350) as amended...is null and void. A police officer as a public officer shall compulsorily retire at the age of 60 years and otherwise." [@ page 353 of the judgment].

Though this case, contrary to the claim of the majority of their Lordships, is not on all fours with the case I brought, make your own judgment whether it supports the conclusion reached by their Lordships in the majority.

I shall be back.