In the heart of bustling Accra, 22-year-old Amina wires a solar panel to a rooftop, her movements confident and precise.

She didn’t learn this at a university. She honed her craft at a local Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) centre.

Amina’s story is not rare; it is the new face of African progress.

TVET, long stigmatised as a "last resort" for academic underachievers, is undergoing a quiet revolution across the continent. And it is about time.

Africa's youth population is booming—by 2030, over 375 million young people are expected to enter the job market.

Yet, most economies are struggling to generate enough white-collar jobs. In this reality, TVET is not just relevant; it is essential.

Skills, Not Degrees

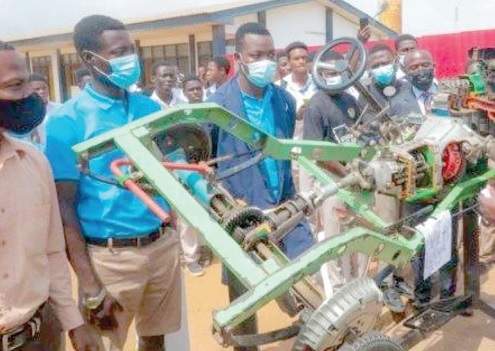

A diploma may open a door, but a skill builds the house. From Ghana's automotive hubs in Suame Magazine to Rwanda’s innovative TVET policy that blends ICT and entrepreneurship, we are seeing a critical shift: skills are becoming currency in an informal yet vibrant economy.

In Kenya, "Jua Kali" artisans—mechanics, carpenters, tailors—contribute over 34% to GDP, yet most are informally trained.

Imagine the potential if this sector were formalised through quality TVET.

More than just technical ability, modern TVET programmes emphasise creativity, problem-solving and digital literacy. In Uganda, youths trained in carpentry now use CNC (computer numerical control) routers to make precision furniture for export. Skills like these are not just for economic survival; they are tools for national transformation.

Overcoming the Image Problem

Despite its potential, TVET in Africa suffers from a serious image problem. Many parents still see it as a second-tier option, a contingency plan. But the truth is, a skilled plumber in Lagos often earns more than a graduate in sociology.

What we need is a cultural pivot. Governments and media must showcase TVET success stories, like the young Ethiopian women building drones in Addis Ababa or the South African mechanics innovating electric vehicle retrofits.

These are not the faces of failure—they are forerunners of a self-reliant Africa.

The infrastructure challenge

Excellent TVET requires investment in workshops, instructors and updated curricula. Many institutions still use outdated equipment and methods that don’t match modern industry needs.

Take Nigeria: although the National Board for Technical Education oversees over 500 TVET institutions, many lack the tools to teach 21st-century skills.

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) offer hope.

The African Development Bank’s “Jobs for Youth in Africa” strategy aims to equip 50 million youths with employable skills by 2025.

Similarly, Siemens and Volkswagen (VW) have supported TVET hubs in South Africa, ensuring that training aligns with industry standards.

Women in Trades: A Force Untapped

Less than 30% of TVET enrollees in sub-Saharan Africa are women, despite high unemployment among young females.

The gender gap is not about capacity—it’s about culture. Breaking stereotypes, like "mechanics are for men," will unleash a massive untapped labour force.

Look at Senegal’s Femmes Battantes initiative, where women are trained in welding, plumbing and even coding. Not only do these programmes empower women economically, they reshape communities by challenging gender norms.

The Way Forward: A Skill-Focused Africa

For Africa to reap its demographic dividend, it must invest where it counts: in skills.

This doesn’t mean abandoning academia but embracing alternatives that are practical, inclusive and forward-looking.

Let us envision a future where a young man in Malawi doesn’t need to migrate for work, because he’s been trained to maintain agricultural drones.

Where a young woman in Ghana or

Tunisia builds mobile apps tailored to her community’s needs. Where TVET is not a “backup plan” but the design for prosperity.

TVET is not just an education strategy. It is a development strategy. And in Africa, where innovation meets necessity daily, it might just be the continent’s most powerful untapped engine for economic growth.

James Attah Ansah is an Educationist and Author.

Email: esem1ansah@gmail.com

Charles Ekornunye Ansah is a Member of The Chartered Institute of Tax Law and Forensic Accountants-Ghana (CITLFAG), and an employee of Ghana TVET Service.

Email: ekornunye@gmail.com