In the last two years, much of the discourse on the Ghanaian economy has been dominated by the country’s IMF Programme.

The 2022 Budget Statement and subsequent mid-year reviews have been presented in the context of the program benchmarks, its targets and how our growth and stabilisation agenda will be achieved by our participation in the Programme.

In 2022 when we signed up for the Program, inflation was 54.1%, the Cedi had lost 54.2% against the US Dollar, and interest rates ranged from 35.5% on bank lending rates to 36.4% on the 91-day treasury bill.

Our fiscal position was -11.8% of GDP, and our exposure to domestic, bilateral and multilateral creditors on various debt instruments was USD 43.9 billion (93% of GDP). Our import cover has depleted to 2.7 months.

When we approached the IMF our situation was described by the Bretton Woods institutions as “suffering from large external shocks exacerbated by pre-existing fiscal and debt vulnerabilities, resulting from loss of international market access, increasingly constrained domestic financing, and reliance on monetary financing of the government.

Decreasing international reserves, Cedi depreciation, rising inflation and plummeting domestic investor confidence eventually triggered an acute crisis”

For a “paltry” Special Drawing Rights (SDR) 2.242 billion (304 percent of Ghana’s quota or about US$ 3 billion), Ghana committed to the following, aimed at restoring macroeconomic stability and debt sustainability, while laying the foundations for higher and more inclusive growth:

Fiscal consolidation

Tight monetary and exchange rate policies; Preservation of financial stability; and Reforms to governance.

For a country, which boasts of the largest gold production in Africa in an environment where commodity prices have been favorable; a country that controls at least 30% of cocoa beans production, in a US$100 billion industry, among other resources, should we be hand-cuffed with “conscripting” Program benchmarks that are making life unbearable for the ordinary Ghanaian?

The objectives may be laudable, but in our opinion implementation has ignored the unique context of a large informal economy, with players whose quality of life goes beyond macroeconomic variables.

We have signed up to a Program which partly aims at “.......... wide- ranging reforms to build resilience and lay the foundation for stronger and more inclusive growth.”

Two years on

Have interest rates dropped enough to make credit affordable to Ghanaians to accelerate business growth to make the market trader’s business more profitable?

Has our Cedi been stable and strong and capable of holding its own against the US Dollar to make imported goods and services (which Ghanaians have developed an insatiable taste for) cheaper?

Have we tightened our belts on expenditure to match our revenues which are reported to be growing on the back of severe taxation?

Have we brought our debt overhang to sustainable levels? Have we made any progress in dealing with structural rigidities in agriculture, industry and services to transform our economy?

Have prices of goods and services consumed by the ordinary Ghanaian been affordable to reflect the decreasing rate of inflation the figures are showing?

Finally, is our growth and stabilization mantra a realistic objective or does it continue to be a moving target?

Our views and perspectives on the 2024 mid-year Budget review discusses Ghana’s performance since signing up to the IMF Programme.

We trace trends in the key targets and objectives set by the IMF to help us “to restore macroeconomic stability and debt sustainability and includes wide-ranging reforms to build resilience and lay the foundation for stronger and more inclusive growth.”

The foregoing looks at fiscal and monetary developments and how efforts in achieving the afore-mentioned objectives have impacted the lives of Ghanaians. We also assess the extent to which Program outcomes impact the outlook.

Sector Development

Ghana's economic growth has transitioned from being agriculture-dominated to being driven by the industry and services sectors. While this shift might indicate a move towards a more diversified and modern economy, it conceals some underlying issues.

The services sector, now a major part of GDP, is largely informal and characterized by small-scale businesses with low productivity and limited access to formal financial systems and infrastructure. This limitation hinders the sector's potential for substantial growth and modernization.

The industrial sector's growth is primarily driven by the mining and extractive industries, including gold, oil, and bauxite. However, the sector's reliance on exporting raw materials makes the economy vulnerable to global price fluctuations.

Minimal value addition means Ghana misses out on higher margins, job creation, and the development of related industries, while still heavily relying on imports for various goods.

This dependence further strains the demand for foreign exchange and puts pressure on the national currency.

Program outcomes so far do not suggest that Ghana is on the path to any structural transformation to effectively address its long-standing economic challenges. Import dependency remains pervasive.

This drags our Cedi along to sustain the structural fragilities. The Cedi has lost 18.6% against the US Dollar. Even though this is better than prior years, it makes our case no better.

Monetary developments

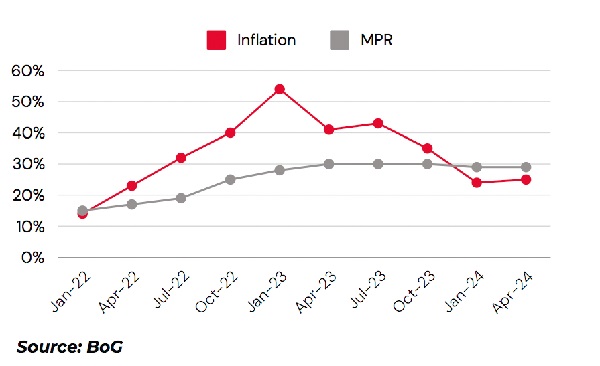

Inflation surged from 10% in 2021 to a peak of 54.1% in December 2023, before falling to 22.8% at mid-year 2024. This decline occurred after the government's US$3 billion IMF bailout agreement.

While the government attributes this drop to the IMF program, its direct impact raises a number of questions. General price levels seem to be more stable.

Prices of “bread and butter” the average Ghanaian thrives on have skyrocketed, forcing many to re- organize their dietary intake towards less nutritious food.

Cars have been parked, medical appointments for the aged and less privilege have been rescheduled.

The impact of the DDEP has been debilitating, with some investors losing up to 40% of their capital.

Cost of production has soared and many hitherto promising businesses have collapsed.

Income levels have not been adjusted to cushion the average Ghanaian worker.

According to the World Bank’s latest report, an additional 850,000 Ghanaians have fallen below the poverty line since the 2022 debt crisis.

The UNDP estimates that the number of Ghanaians living in multidimensional poverty has risen to between 8.1 and 8.4 million, which is about 25% higher than the pre-pandemic figure of 6.5 million.

The cost of borrowing has remained very high. Businesses cannot be expcted to thrive with bank lending rates hovering in excess of 35% per annum or when every pesewa is taxed in the name of fiscal austerity.

The aspiration of a private sector led growth will remain a hoax under these circumstances.

If we manage to reduce treasury bill rates towards mid-30% from almost 40% at the beginning of the Program, we have not stopped government from crowding out the private sector. At such rates, no business can compete with government for funding and government will continue to dominate business in Ghana.

The financial sector stability initiatives are very well intended. The IMF Country Report No. 23/168 (May 2023) concluded that “The aggregate NPLs had declined from 17 percent in 2019 to about 15 percent at end-2022, and the sector had been well- capitalized except for a few institutions.”

The 2024 mid-year Budget review affirms this position, and indicates that ”........The banking sector rebounded in 2023 with an improved balance sheet performance in December 2023 on the back of increased liquidity flows from deposits and shareholders’ funds.

Total assets increased by 29.7 percent to GH¢274.9 billion as at the end of December 2023. Total investments increased by 47.5 percent to GH¢100.2 billion, driven by the bank’s reallocated portfolios towards short-term investments in response to the increase in short- term”

It also indicates that total credit remained sluggish in 2023, dropping to a third of its growth at the end of December 2022 rate of 29.1% to 10.9% at the end of 2023. The private sector was affected the most by the decline in credit.

Banking assets quality took a hit as NPLs increased to 20.7% in December 2023 from 16.6% in December 2022, a sign that adverse selection is rife in the marketplace.

The unification of currency holding for Cash Reserve Ratios (CRR) and adjustments in the Loan Deposit Ratios (LDRs) of banks by the Central Bank has triggered some reactions.

The intention to push the banks to disburse more loans to productive sectors to help resolve the excess liquidity to contain inflation is laudable.

The question however is, what is driving excess liquidity in the market? To what extent does the level of liquidity in the economy after the DDEP be explained by less investable options available to the banks? It is important to take a second look at these monetary policies to deepen financial intermediation in a market that is still reeling under pressure.

Exchange rate developments have caught more attention in the last 2 years. Following the announcement of the IMF Program, rates stabilized immediately.

The structural causes of the depreciation phenomenon have however still not been addressed. The Cedi is still very fragile and any attempts at market intervention have not been beneficial, other than wiping our meagre foreign exchange reserves.

Again, structural transformation and suggestions about a more liberal foreign exchange regime are worth considering.

External sector

Ghana is highly dependent on importing finished and semi-finished goods for consumption and industrial purposes, resulting in a substantial demand for foreign exchange (forex) across various sectors, including consumer goods, industrial inputs, machinery, and technology.

The economy faces significant challenges due to its reliance on primary commodities like gold, oil, and cocoa for export revenue, which are subject to volatile global price fluctuations.

In the first half of 2024, Ghana's total exports increased by 13.4% to US$9.23 billion, driven by strong growth in gold exports. Low earnings from cocoa, however offset this growth as Ghana experienced a significant drop in cocoa production. Forward contracts by COCOBOD to secure funding prevented the country from fully benefiting from the tripled prices at the end of the season.

Ghana's international reserves have fluctuated significantly over the past four years. Reserves were at $9.7 billion, but by the end of 2022, they had dropped to $6.6 billion due to increased external debt servicing, high import demand, volatile commodity prices, and inflationary pressures leading to cedi depreciation.

It is our expectation that the mid-year import cover of 3.1 months will be maintained to keep the country in touch with the Program target.

Fiscal developments

Structural Fiscal Reforms under the Program is targeted as the key fiscal consolidation anchor. Structural weaknesses in revenue mobilization continues to be a major bane to any transformational growth in revenue growth.

Even though a lot has been said about the other side of the equation, expenditure rationalisation, in our opinion remains a challenge.

Total Revenue and Grants for the first half of 2024 amounted to GH¢74,651 million (7.1% of GDP), 1.9 percent below the target of GH¢76,067 million (7.2% of GDP).

Total Expenditures (commitment) amounted to GH¢ 95,935 million (9.1% of GDP), 8.4 percent below the budget target of GH¢ 104,769 million (10.0% of GDP).

While the removal of Central Bank financing has been helpful in reaching the fiscal deficit/GDP ratio of 5%, tightening our belts to the detriment of CAPEX financing (infrastructure financing in particular) will not generate the growth we seek.