Nigeria’s eNaira, one year after

Nigeria’s eNaira was the first Central Bank Digital Currency in Africa and only the second in the world when it launched in October 2021, but a growing number of countries across the globe are now planning to follow suit with their own CBDCs.

What can they learn from Nigeria’s experience? Jookyung Ree is an economist in the IMF African Department and assigned to Nigeria when the CBDC was introduced.

Ree has since studied its impact on the economy and found that existing mobile money networks are proving a challenge to the eNaira’s adoptability.

In this podcast with Bruce Edwards (BE), Jack Ree (JR) says the eNaira will need to complement mobile money systems to convince more Nigerians to use it.

(BE):Nigeria's eNaira was one of the first of a growing number of central banks wanting to launch their own, but what do Central Bank Digital Currencies or CBDCs actually bring to the table?

(JR):From the customer's point of view, the utility that the existing mobile money provides is very similar to the utility that CBDCs can potentially provide, and there are already like 25 mobile money operators... So somehow the CBDC might not mean a game-changing value edition.

(BE):In today's program, what we can learn from Nigeria's CBDC experience and how its Central Bank might convince more Nigerians to use it.

(JR):The next two, three years will be very important. They will need to make the right strategy in terms of setting relationships with mobile money, so that either compliment or substitute. Probably in Nigeria's case it's going to be a complimentary model that makes sense.

(JR). I'm an Economist working for the African department. Currently working on Zambia, but my previous assignment was in Nigeria.

(BE):Jack Ree is also the author of a research paper called, Nigeria's eNaira, One Year After. Check it out at imf.org.So Nigeria was the first on the continent or the African continent and only the second in the world to launch a CBDC or Central Bank Digital Currency. Why would it choose to do that? I mean with all the other challenges the country faces, why did the government make this a priority?

(JR):That's a very interesting question. I think that certainly there has been some political backing because the former president, Mr. Buhari, himself was quite interested in doing something digital, and Nigeria being seen as the champion of some sort of innovative digital revolution in Africa.

So probably that's one of the political drives that is coming from that front, but that's speculative. So based on the central bank's own account of their motivation, essentially three big reasons.

The first motivation is financial inclusion, which is not really much of a problem for many of the advanced central banks. For example, Bank of England recently did quite deep research on whether or not to do a CBDC on its own. And for Bank of England financial inclusion is not much of a problem.

But in Nigeria a lot of people don't have bank accounts. It's a big country, populous country, 38 million adults don't have a bank account, which is almost 40% of total of their population.

(BE):38 million adults don't have bank accounts?

(JR):Right. So that's quite large. But Nigeria is one of the most advanced countries in Sub-Saharan Africa in terms of mobile phone penetration. So most people just have not fancy iPhones, but the simple fold-up phones or feature phones, everybody carries.

So the gap between digital penetration and banking sector penetration basically makes people think that if we make all the financial access digital, probably we can just do a very quick and large fix to this financial inclusion gap. So that was one reason. And the other reason is remittances.

Nigeria is one of the largest remittance recipient countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Before pandemic, the size of the annual remittance that Nigeria alone has received was close to 25 billion dollars per year.

That's a lot of money, but since the pandemic, for a lot of reasons, the remittances really fell down quite dramatically and it never recovered to the pre-pandemic level.

And then along with many other developing countries, they thought that making remittances cheaper may be the way to go. Currently, for remittance through the, what's called, International Money Transfer Operators, IMTOs like Western Union, typically costs like seven to 8% margin in every dollar you send.

And with the CBDC you can, in theory, bring down that close to zero. So that was another big reason.

Third reason is the presence of large underground or informal economy in Nigeria.

So the size of the informal economy in terms of employment is almost 80% in Nigeria because all our people in non-urban areas, they're all sort of informal.

So informal economy means that a lot of money are going outside the banking system and not really tracked and really not captured by the tax net either.

So CBDC like the model that Nigeria use, it's so called account-based, which is different from crypto coins like Bitcoin, which is untraceable.

The account-based CBDC should be, in theory, fully traceable if there is a need for some sort of tax audit and stuff. So that's another motivation.

(BE):So your research is a bit of a stock-taking on this CBDC that was launched now in, what year was it launched?

(JR):That was 2021. October, I think. Yes.

(BE):And you started doing your research about a year after it was launched?

(JR):Yes.

(BE):Looking at how effective it was. So how have Nigerians accepted the CBDC? Are they using it to the extent that they were hoping or at least that the government was hoping that they would or the central bank was hoping that they would use it?

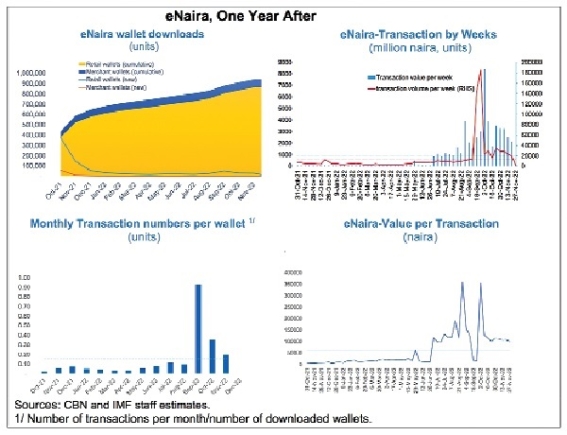

(JR):That's a mixed bag because first of all, it's very difficult to get any statistics or data on CBDC usage. So I was very privileged to have the courtesy of the central bank to share the data, very granular data with me. But the data essentially says that after one year the number of wallets... CBDC has to be downloaded as a wallet in your phone, like an app. And the number of downloads was less than 1 million, something like 860,000 as of end of November.

That's the last data point that you got. That- compared to Nigeria's huge population, it's like less than 1% of the total number of bank accounts. So that's fairly small, fairly modest, if I may say.

And what is a little bit more somewhat disappointing was a slowness in terms of the usage because a lot of wallets that has been downloaded, well, not actually used, they were remain in the state of dormancy. My paper found that about 98.5% of the total wallets that has been downloaded was not used more than once-

(BE):Wow.

(JR):... For any given week. So that's fairly low. But I would say that it was not really a big disappointment for the authorities because the central bank from the beginning said that we are actually providing ourselves as the Guinea pig to the rest of the world.

We are the only adopter, we're going to do this very cautiously. So they always say that they were going to take a baby step approach.

(BE):So adopting has not gone well, but over the course of the year or since it was launched, it's been very stable? There haven't been any crises in terms of it crashing or the infrastructure seems to have worked?

(JR):That's a very interesting, important question. In fact, because there are other central banks in the Caribbean region that had outages several months after launching their own CBDC. And if that happens, there's just the credibility and trust of the new system will go down the hill. And that didn't happen in Nigeria. So in fact, it's quite laudable that the system, even though that adapted very sophisticated and experimental technology like distributed ledger blockchain, all these things, it showed operational resilience and they were able to establish 24/7 continued operation without disruption for at least one full year and up to now.

(BE):That's interesting. So CBDC is new to Nigerians, but mobile money is not, they've been using mobile money for many years now and mobile money seems to have been taking care of a lot of the inefficiencies of- Jack Ree:Definitely.

(BE):... Paper currency. How do CBDCs or how can CBDCs complement the mobile money network and how successful has it been at doing that?

(JR): So the big discussion that goes beyond just the case of Nigeria is the relationship between existing private digital money. Typically, it's going to be mobile money because mobile money has been very successful across the continent. Outside Africa the most probably successful, for example, would be India.

But here as it's been very successful and it has been really leading digitalization of finance, digitalization of the economy and so on. And given that background, whether CBDC at the retail level is actually needed, is going to be redundant, is going to be irrelevant, doesn't really have space to grow or the only thing that is going to do is to just crowd out the private sector in terms of the same use cases...

So whether we would want to go down the route or not is something that is still being debated.And the debate is much larger than my own paper and it is debated in within the IMF, within BIS, many circles now. But what I can say is that there are two models. One is the substitution model where CBDC essentially competes with the mobile money. I think that approach can make sense in some countries where mobile money is extremely monopolized by maybe just one company.

An example could be Kenya where M-PESA is like a 99.9% of the market. And that kind of monopoly is very going to be very difficult even for the supervisor, not only from the antitrust point of view, but also from financial supervision point of they become just too powerful to be regulated. So that could be a problem and maybe the public sector can be the only way to bring some sort of competition into the market.

So I understand some African countries are considering the usefulness of the CBDC in that perspective. But in the case of Nigeria, in fact, mobile money market is not very active as in case of Ghana or Kenya due to existence of too many mobile money... and markets is very fragmented.

And just interoperability between different mobile money is very costly. So in that kind of case it probably makes sense for CBDC to become a complimentary element of the mobile money.

So both things working together in an integrated wallet. So if you have say MTM mobile money and that is integrated with the eNaira so that if you walk into the shop and if the shop doesn't receive MTM money but some other, you can still use your backup line which is CBDC, that would make more sense in terms of complementary, I think, in markets like Nigeria.

(BE):But what would be the incentive for the mobile money provider to work with the central bank? What's in it for them?

(JR):That's an excellent question. So maybe the traditional way of central banks in dealing with the integrating central bank system with the private sector providers is through regulation.

So just forcing them to somehow implement their interoperability or at least link their mobile money wallets with the CBDs wallet is one way.

But then there is also a business case for both the central bank and mobile money can win because in countries like Nigeria where mobile money, there are like 25, 26 mobile money operators-

(BE):Wow, that's a lot.

(JR):That's a lot. And so it's very difficult for any single mobile money operator to be dominant.

And if you're not dominant, the consumers will always be divided into various other mobile money and that makes the universal usage over your mobile money very difficult. So if your mobile money product is integrated with

CBDC, and CBDC is more likely to be accepted by other merchants, that increases the motivation for people to actually get mobile money wallet itself.

So for mobile money to increase its own penetration in the public, a regulation like this for them, to mandate them to integrate- link it to the CBDCs might actually be a good thing for them to enhance the attractiveness of the mobile money to the consumers.

(BE):You talked about remittances earlier, which are important to Nigeria as they are in many countries, representing more than 5% of GDP in Nigeria. How do or should CBDC help people send money back home?

(JR):In theory, in an ideal world, CBDC is going to... Kind of a direct arrangement between the last mile customer, retail customer and at the central bank without any intermediary.

So if what is called a multi-CBDC system, which is actually being experimented by a number of central banks at the moment, including South African Central Bank and Singapore, several countries group together and they basically create some sort of distributed ledger or centralized database system that is not just single currency but multiple currencies.

And these multiple currencies will be me buying, say South African Rand using a Singapore dollar will be recorded in a single ledger. So single recording and single ledger means that all the transactions is going to be settled instantaneously.

So that's what's called atomic settlement, meaning that it's instantaneous, meaning that there is no time gap between trading and settlement.

And also simultaneous, meaning that all legs of those transactions, like in the foreign exchange transactions in the example that we said before, Singapore dollar lag and the rand lag will be settled at the same time without any sequentiality.

(BE):So there's no intermediary banking?

(JR):No intermediary and most importantly there is going to not involve the banking system. So right now- Bruce Edwards:Fees?

(JR):... All the transactions are done through what is called correspondent banking arrangements, which is very costly and very lengthy. And that takes long time. And that it also restrained by banking holidays on working hours and so on.

But in this ideal world where there's a multi-CBD system, essentially the cost of remittance can go to zero. But that's an ideal world where there is some sort of multilateral solutions.

For example, organizations like IMF and BIS basically lead a global initiative in terms of remittances. But we're a long way to go there because we are not even sure how many countries want to do the CBDC experiment themselves...

(BE):Exactly. And it brings me to my last question actually. So how significant is this eNaira experiment for Sub-Saharan Africa's broader financial system? Will this prompt, do you think, other countries to adopt their own CBDC?

(JR):That's a very interesting question. And in fact that goes much beyond my own papers focus, in Nigeria. I also work as a part of the IMFs African department's CBDC group network and we are conducting a survey of all African countries on where they stand in terms of CBDC plans and what their thinking is, all these things.

So we don't know yet, but I think Nigeria's first year experience really gives mixed signals to the countries.

Positive signal is, in terms of the fact that Nigeria was able to build and maintain that system without the major breakage, which itself is something quite impressive from Sub-Saharan African perspective because everybody would've thought that okay, probably is going to be a dead-on-arrival type of failed experiment and it didn't happen.

(BE):Which it was not.

(RE):Which it was not. So that basically shows that maybe motivate many countries and maybe give an inspiration to other countries.

Nigeria can do that. Ghana can do that. Or South Africa can do that... kind of sentiment can arise.

But at the same time, Nigeria was not able to still make a breakthrough in terms of mass adoption. So it's still very, very limited adoption there. And to make a breakthrough, the next two, three years will be very important.

They will need to make the right strategy in terms of setting relationship with the mobile money. So that either compliment or substitute, probably in Nigeria's case is going to be a complimentary model that makes sense.

And maximizing the synergies with the digital revolution or digital innovation that is going in the private sector, and then making a breakthrough in terms of remittances.

Nigeria's specific reason why it cannot work in remittances so far is because the official exchange rate has long been controlled, and now if you go to the black market, black market is very easily reachable and very large... transactions in the black market, the spread, until a while ago, has been like 78%.Bruce Edwards:Wow.

(JR):So in terms of a dual exchange rate system. And if your CBDC offers only the official rate- it's hugely penalizing, nobody's going to want to go that route. Everybody's going to just carry US dollars... But then Nigeria made a big move lately in terms of floating the exchange rate. So I think all the signs are quite hopeful and the new government definitely has a good opportunity for them to harness.

(BE):So it's a question of creating incentives. Consumers, users, potential users want to use it because they get some kind of benefit from, whereas it's not all that obvious at this point.Jack Ree:Definitely.

(BE):Jack Ree is a Senior Economist in the African department with the Zambia team. Thank you very much.Jack Ree:Thank you so much, Bruce.Bruce Edwards:You'll find Jack Ree's working paper on the eNaira One Year After at imf.org.And you can hear more IMF podcasts on Apple Podcasts or Spotify or wherever you listen. You can also follow us on Twitter at IMF_Podcast

I'm Bruce Edwards, thanks for listening.