Introduction

Methane, a potent greenhouse gas over 80 times more powerful than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period, has emerged as both a critical climate risk and a strategic energy opportunity. In Ghana, where natural gas fuels most thermal power plants, addressing methane emissions offers a dual advantage: environmental protection and enhanced energy security. However, methane rarely features prominently in national climate conversations, despite its rising levels and far-reaching consequences.

This essay is part of a broader effort by the Africa Centre for Energy Policy (ACEP), with support from the Clean Air Task Force (CATF) and funded by The Lemelson Foundation, to build awareness, policy engagement, and institutional capacity for methane abatement across Africa. It explores how effective gas commercialisation and methane reduction strategies can be integrated into Ghana’s energy and climate planning. It highlights lessons from past energy crises, infrastructure progress such as the Atuabo Gas Processing Plant, and the urgent need to address renewed gas flaring. Through effective methane management, Ghana has a unique opportunity to lead on both climate action and sustainable development.

The Rising Impact of Methane on Climate and Energy Security in Ghana

Despite the growing relevance of methane in global and national climate agendas, Ghana’s policy and public discourse have not kept pace with its rising emission trends. Between 1990 and 2022, methane emissions in Ghana increased by about 260%, mainly driven by developments in the energy and waste sectors. These emissions contribute not only to climate change but also to the formation of ground-level ozone, which impacts air quality, respiratory health, and agricultural productivity.

More critically, methane plays a significant role in Ghana’s energy system. As the main component of natural gas, it powers the majority of the country’s thermal generation capacity. However, this reliance exposes a key vulnerability: the availability of fuel. Installed capacity alone does not guarantee a stable electricity supply unless matched by dependable fuel inputs. With gas now a strategic component of Ghana’s power mix, efficient gas management and commercialisation are essential, not only to reduce emissions but also to ensure energy reliability and economic resilience.

From Crises to Gas-led Recovery

Major power crises in the 1990s and early 2000s were occasioned by significant drops in the water levels of the country’s hydroelectric sources, which were the primary source of electricity. However, increasing electricity demand made it clear that hydroelectricity alone was insufficient, prompting a gradual but strategic pivot toward thermal generation.

The government secured credit to build the 300 MW Takoradi Thermal Power Station (TTPS), commissioned in 1997. In 2000, the Takoradi International Company (TICO), a joint venture between the Volta River Authority (VRA) and the Abu Dhabi National Energy Company PJSC (TAQA), added 220 MW and later expanded to 330 MW in 2014.

Most thermal plants relied on liquid fuels, which made electricity production highly vulnerable to global oil price fluctuations, contributing to the fiscal pressure on the government to either pass on the costs to consumers or subsidise electricity tariffs. In response, Ghana ramped up efforts to secure a more stable and affordable energy source. For example, the West Africa Gas pipeline was completed in 2008, and Ghana began to offtake gas from the pipeline in 2009. The government has since invested in gas production, processing, and transport infrastructure to boost domestic supply.

Recognising the need for a coordinated approach, the Government of Ghana developed the Gas Master Plan, a comprehensive framework to guide the sustainable development and utilisation of natural gas. Other policy documents, such as the national energy policy, also provide for the adoption of natural gas as fuel that could be utilised for power generation and transportation to address energy security issues.

The transition from liquid fuels to natural gas has also been integrated into Ghana’s climate action agenda. For example, the National Climate Change Policy seeks to eliminate gas flaring by establishing efficient infrastructure and mechanisms for processing and using by-products from oil fields. In its first Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs), Ghana identified replacing crude oil with natural gas in thermal plants as a key mitigation measure. The government projected that this shift could result in fuel cost savings between $94 million and $109 million.

Today, domestic gas forms about 70% of the total gas supply. Ghana’s domestic gas sources include associated gas from the Jubilee and TEN fields, as well as non-associated gas from the Sankofa Gye-Nyame fields. Domestic gas supply is augmented with imports from Nigeria through the West African Gas Pipeline.

The Atuabo Gas Processing plant is central to Ghana’s gas Utilisation Strategy

The government of Ghana recognised the need to construct a gas processing plant to process gas produced from the Jubilee and TEN fields, which led to the establishment of a processing plant at Atuabo in 2014. In 2015, the Atuabo Gas Processing Plant processed an average of 72 million standard cubic feet per day (mmscfd) and has since provided between 60 mmscfd and 100 mmscfd, primarily for power generation as of 2024.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has attributed notable environmental benefits to Ghana’s natural gas infrastructure, particularly the Atuabo Gas Processing Plant. This facility played a crucial role in reducing routine gas flaring. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, the percentage of flared gas relative to total natural gas production declined from an average of 38.6% before 2014 to 13% by 2018. This reduction reflected considerable progress toward the country’s zero flaring policy as outlined in the Petroleum (Exploration and Production) Act 2016

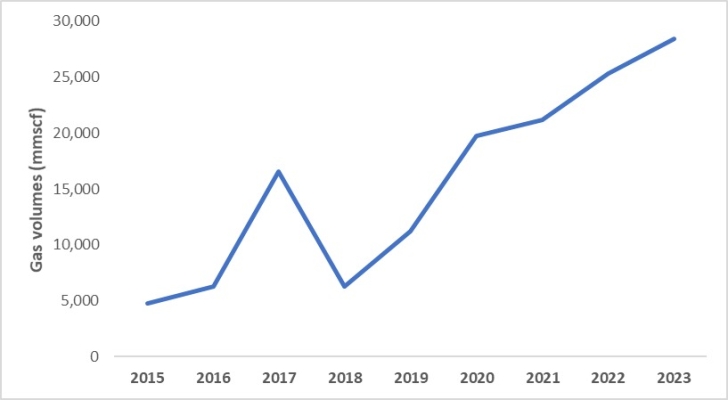

However, this progress has faced setbacks due to delays in the planned second phase of processing infrastructure. The limited capacity of the existing Atuabo plant constrains Ghana’s ability to fully commercialise increasing gas volumes from the Jubilee and TEN fields. As a result, operators have had to flare substantial quantities of gas that could otherwise have supported domestic power generation. Between 2020 and 2024, approximately 102 billion cubic feet (bcf) of gas were flared from these fields. This volume is equivalent to an average daily supply of about 55 mmscf.

Figure 1: Gas Flaring from Upstream Operations

Data Source: Public Interest and Accountability Committee (PIAC)

Impact on Energy Security

The limitations of Ghana’s current gas processing infrastructure have significant consequences for national energy security and economic stability. As electricity demand grows, the domestic gas supply is nearing its capacity threshold. The 2025 Energy Supply Plan projected a demand of approximately 544 mmscfd of gas, but actual availability is about 415 mmscfd, exposing a substantial supply gap. This shortfall forces power producers to turn to expensive liquid fuels, such as Light Crude Oil (LCO), Heavy Fuel Oil (HFO), and Diesel Fuel Oil (DFO), to meet their generation needs.

The financial burden of this dependence is severe, especially within a power sector already weakened by systemic inefficiencies and revenue shortfalls. Diesel, for example, costs nearly three times Ghana’s weighted average cost of gas, while HFO and LCO cost nearly double that amount. These high costs have serious budgetary implications. According to Ghana’s Minister of Energy, the country needs approximately $1.2 billion in 2025 to procure liquid fuels.

“This year alone, we estimated that $1.2 billion is required to procure liquid fuel….but when we use gas, that will save us about 50% to 60% of the cost of liquid fuel. If we had a gas processing plant, it means that we would have been saving about $600 million this year alone, and that amount is enough to build the gas processing plant.”

His remarks highlight a critical missed opportunity. Thus, the failure to optimise domestic gas results in higher fuel costs and diverts scarce fiscal resources that could be used to fund infrastructure development.

Conclusion

Methane abatement is not just an environmental obligation but a strategic imperative for Ghana’s energy future. The resurgence in flaring driven by infrastructure bottlenecks undermines both climate commitments and national energy resilience. Through investing in expanded gas processing capacity, Ghana can reduce methane emissions, optimise its domestic energy resources, and save significant fiscal resources currently spent on expensive liquid fuels.

The experience of the Atuabo Gas Processing Plant demonstrates that infrastructure can play a transformative role, but only if it keeps pace with growing energy demands and emission realities. Future investments must prioritise timely expansion and regulatory enforcement to capture gas that would otherwise be wasted. Technical insights and philanthropic support, including contributions from partners engaged in methane management and innovation (such as the CATF, ACEP and the Lemelson Foundation), can help Ghana advance a forward-looking gas strategy.

Now is the time to elevate methane mitigation in national discourse, not as a side issue, but as a central pillar of Ghana’s energy transition. Through this action, the country can avoid repeating costly mistakes and instead position itself as a leader in climate-smart energy development across Africa.