Financing fight against TB

U.S. President Trump’s spending freeze on foreign aid marks a significant challenge for the international development community, and many experts warn that diseases will surge.

During this time of uncertainty about the future role of the world’s biggest donor, the Global Fund stands as a beacon of hope.

Since the beginning of the millennium, the Geneva-based multilateral organisation has been fighting one of humanity’s oldest scourges, infectious disease – and specifically the three big killers, malaria, HIV and tuberculosis.

Through targeted funding and innovative strategies, the Global Fund has made significant breakthroughs against malaria and HIV. Now, the time is ripe to sharpen its focus on tuberculosis.

Allocations

Nearly one-third of the Global Fund’s 2023-2025 allocations have gone to the fight against malaria, amounting to some $4.17 billion.

These funds have supported large-scale distribution of insecticide-treated bed nets and rapid diagnostic tests, drastically reducing transmission rates.

Countries such as Rwanda and Zambia have seen remarkable declines in malaria cases and deaths.

For HIV, the Global Fund is spending $6.48 billion, amounting to nearly half its allocations.

In the past decade, the Fund has facilitated access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) for millions, helping to transform HIV from a fatal disease into a manageable chronic condition.

By promoting education and prevention, particularly in vulnerable communities, the Global Fund has empowered individuals to take control of their health.

Together, these efforts have saved countless lives and advanced global health security. But it is now time to reassess.

Tuberculosis prevention and control has been allocated $2.4 billion or just 18 per cent of the Global Fund allocations budget – and has received less than HIV or malaria in every year since the Global Fund was created.

But tuberculosis now kills more people than HIV and malaria together. It is by far the world’s leading infectious disease killer. Not only do malaria and HIV receive far more resources from the Global Fund than tuberculosis, but they also get much more global publicity and media coverage. Tuberculosis, in comparison, is a neglected, forgotten and often ignored disease.

History

To understand why, we need to look at the history of tuberculosis. For people in the rich world today, the disease is little more than a dim memory of a bygone era. But back then, tuberculosis was frightful.

In the 1800s it brought a tsunami of death, killing one in four across Europe and the US. For most of the 1800s, New York City’s tuberculosis death rate alone was higher than the total death rate in the city today.

Across the 1800s, tuberculosis was a much bigger killer than the recent global COVID-19 pandemic managed even in its worst year. Over the past two centuries, tuberculosis has likely killed one billion people.

Yet, almost like magic, tuberculosis has disappeared in the rich world. Antibiotics and a childhood vaccine, combined with better living standards, rudimentary public health measures, and subsequent treatment breakthroughs, mean that the disease has been largely eradicated in wealthier countries.

But mostly, tuberculosis has lost the attention of the rich world. Not so for the world’s poorer half, where tuberculosis still claims nearly 1.3 million lives every year. For comparison, that is greater than the combined death toll of HIV/AIDS (630,000) and malaria (619,000).

For more than half a century, we have known how to cure tuberculosis.

Yet, it persists and kills a record number of people in the poorer part of the world. It mostly kills adults in their prime, leaving children without parents.

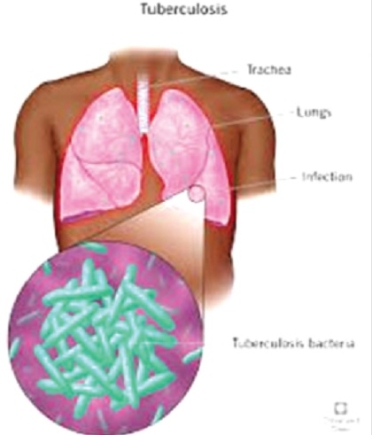

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis has become an illness of poverty. It spreads when people live in close quarters and are unable to afford space, and it thrives among populations who cannot afford basic health care and services.

The most vulnerable, living in slums, migrant areas, mining towns and prisons are also the most voiceless. Tuberculosis has gone from risking the lives of all to just killing those that nobody cares enough about.

Needless to say, this shouldn’t be the way. We know how to defeat the disease. It would take surprisingly few resources.

Research for the Copenhagen Consensus think-tank shows that additional expenditure of $6.2 billion annually could save about a million lives a year over coming decades, making this one of the very best possible development policies.

This spending would enable a much broader diagnosis to end onwards infections and ensure most tuberculosis patients stay on medication, reducing deaths by 90 per cent by 2030.

The benefits, including the reduction in death and disease, outweigh the health care and time costs by 46 to 1.

The Global Fund is in the middle of its three-year replenishment cycle, when it asks the world for more resources.

The world needs to be generous because the Global Fund has shown that it is one of the very best ways to achieve good in the world.

And the Global Fund – as well as development agencies everywhere – need to focus more on the illness that is claiming the most lives, and where investment can deliver an astonishing return on investment.

The writers are South Africa's Minister of Health and the President of the Copenhagen Consensus.