Lessons from the Ghanaian election: No. 1, don’t sign a deal with the IMF

A few months ago, the New Patriotic Party (NPP) seemed mired in party indiscipline manifesting itself in leadership clashes, ethnic divisions and rumours of a spent kitty.

Few could have predicted the dramatic fashion in which the party would rise to overwhelm the ruling National Democratic Congress (NDC) and snatch Ghana’s 2016 presidential and parliamentary elections in such convincing fashion last week.

However, the goose started cooking when the Mahama administration signed a three-year bailout package worth $918 million with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in mid-2015. Who submits to IMF conditionalities going into an election year?

Until Flt Lt Jerry Rawlings in 1983 became the African strongman who could make an IMF austerity programme stick, it was widely believed across Africa that anyone who brought the IMF home would invite a coup d’état.

Successive governments did sign IMF programmes, but after the Highly Indebted Poor Country (HIPC) status years of the Kufuor administration when we declared to the world that we were in need of special assistance, through the short Mills years when the lucky oil finds enabled us to proudly announce that Ghana was now a lower middle-income country, we had thought that we had finally graduated from IMF tutelage.

Purpose of IMF programmes

Not that there is anything technically wrong with IMF programmes. After all, what can be wrong with financial discipline and good accounting? It is just that IMF programmes are designed to stabilise an economy and not to transform it.

Often, stabilisation measures are an indicator that a government has lost the plot. A government that is in control of its economy does not need to turn to the IMF. Thus, keeping a good distance between your finance ministry and the IMF is a good indicator that all is blooming at home.

IMF programmes do not generally make governments popular because they require considerable belt tightening. Though they all claim to be “homegrown,” these ‘structural adjustment’ programmes always have the same macroeconomic stabilisation features.

Whereas transformation implies investment in production, stabilisation by contrast suggests taking an economy off the boil, more austerity, less spending and usually less innovation.

So then the question became, if the NDC thought they could do austerity and win the election, what on earth did they have up their sleeves?

Woyome

For example, how were they going to find money for the 2016 electoral campaign and quash speculation that the GH¢ 51.2 million paid controversially to pro-NDC businessman Alfred Agbesi Woyome in judgement debt was meant to finance the campaign?

Otherwise, why did the current Attorney-General, despite a Supreme Court ruling that Woyome should refund the money to the state, withdraw its application to orally examine the businessman? Why did Rawlings call Woyome a “thief”? Why was he not campaigning for President Mahama?

These questions became more and more troubling as utility bills soared and food prices continued to match the rise in fuel prices, which continued to be regularly adjusted upwards even though, as many pointed out, oil prices were at historically low levels on world markets. Who raises the price of fuel seven weeks before an election?

Some people thought they had found what the ruling party had up its sleeve when former Attorney-General and Woyome case whistle blower, Mr Martin Amidu, cried that President Mahama was Electoral Commissioner, Mrs Charlotte Osei to rig the election.

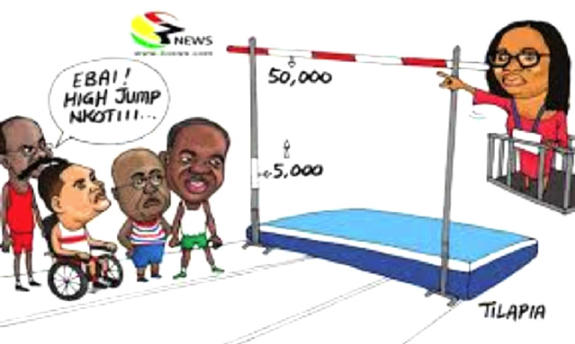

The first sign that the new EC boss was going to get tough had come soon after her appointment in mid-2015 (around the time the IMF deal was signed), when she announced that any party that did not have offices in two thirds of constituencies would be disqualified.

However, after the smaller parties scrambled to meet that requirement, just three months before the December 7, election, the EC raised the cost of filing nominations 500 per cent (GH¢10,000 to GH¢50,000) for presidential candidates and 1,000 per cent (GH¢1,000 to GH¢10,000) for parliamentary candidates.

Mrs Osei’s next move was to disqualify 13 presidential candidates, leaving only candidates for the two big parties, an independent candidate and, curiously, the Convention People’s Party.

Not only were they disqualified on the grounds that their filing forms were not properly filled out, but they were also reported to the police for fraud. The police even started probing how some small parties had raised the money to pay the inflated filing fees.

As the parties abandoned their campaign grounds to run in and out of the High Court, the Progressive People’s Party Flag Bearer, Dr Paa Kwesi Nduom, successfully won a Supreme Court ruling that led to some of the disqualified parties being reinstated. Happily, the ballot papers could now carry seven presidential candidates.

In the midst of this confusion, Ghana’s elephant party — the elephant is the party symbol of the NPP — began trumpeting a series of manifesto pledges that caught the imagination of the populace. One District, One Factory. One Village, One Dam. One Constituency, One Million Dollars. So dizzying were these promises that unschooled presidential aspirant, Madam Akua Donkor, had her own euphoric moment when she pledged One Fisherman, One Sea!

Beyond the current euphoria sweeping through much of the nation though, the NPP is stuck with the IMF programme, at least for the next two years. It remains to be seen how they will rise above Ghana’s worrying high debt ratio, currently around 70 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP), to achieve their ambitious campaign promises.

President-elect Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo has said his plans do not depend for success on dwindling government reserves but private sector participation in the economy.

Whether the NPP can create a model for economic development not seen before in Ghana’s history in which the private sector buys into the manifesto plans of a ruling party and delivers broad-ranging economic and social development is a question that will dominate policy-making over the next four years.