Dismantle shadow state to solve galamsey crisis — Prof. Ayelazuno

Researcher and Senior Lecturer at the University for Development Studies (UDS), Professor Jasper Ayelazuno, has called on President John Dramani Mahama to confront the entrenched power structures driving illegal small-scale gold mining (galamsey), warning that without decisive political reform, efforts to tackle the environmental crisis would fail.

He said galamsey was no longer just an environmental or law enforcement issue, but a symptom of a deeper political illness and state capture, a phenomenon he described as the “Shadow State.”

“The Mahama government must realise that repeating the militarised script of the past, without political reform, will not liberate the state from its captors. This moment calls for bold, principled leadership,” Prof. Ayelazuno said.

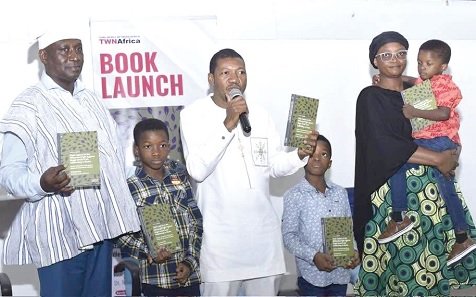

He was speaking at the launch of his new book organised by Third World Network-Africa (TWN-Africa).

The book

Titled; “State Capture in the Militarised Fight Against Illegal Small-Scale Gold Mining in Ghana,” the book explores the paradox of the country’s democratic reputation and its failure to curb illegal small-scale mining (galamsey) between 2017 and 2024.

Co-authored by Dr Maxwell Akansina Aziabah, who is of blessed memory, the book argues that in spite of strong public commitments, military crackdowns, and significant state investment, the crisis not only persisted but worsened—devastating rivers, forests, rural livelihoods, and public health.

It contends that this failure is not due to weak institutions or lack of laws, but rather to state capture, where political and economic elites hijack state institutions to protect and profit from illegal mining.

These elites—including top politicians, traditional authorities, business actors, and segments of the security forces—form a “shadow state” that operates beyond formal accountability.

This informal network repurposes regulatory bodies, enforcement operations, and even legislation to serve elite interests.

Ultimately, the writers challenge dominant narratives that view galamsey as a criminal or technical issue, framing it instead as a structural political crisis rooted in elite complicity and democratic dysfunction.

Solutions

In order to address the crisis, Prof. Ayelazuno outlined a four-point plan.

It entailed dismantling elite capture networks; restoring institutional autonomy; protecting journalists, civic actors, and whistleblowers; and shifting from punitive enforcement to community-led governance.

He also called for a simplified legalisation process for genuine artisanal small-scale miners who mined for survival.

He criticised the government’s failure to declare a state of emergency in affected areas, calling it a missed opportunity to send a powerful political signal and disrupt the informal networks behind illegal mining.

Prof Ayelazuno warned that if the Mahama-led administration failed to act decisively, it risked reinforcing the shadow state and further weakening democratic institutions.

“If the government chooses a different path, he said, it may begin the long but necessary work of restoring democratic control over natural resources, protecting the environment, and upholding the dignity of rural communities.

“The galamsey crisis is not merely a technical security challenge to be outsourced to security forces.

It is a test of whether Ghana’s democracy can be reclaimed from the grip of greed and reoriented toward the common good,” he stressed.