2024 Budget review: Balance scorecard of 2017-2023 growth stability pursuit

Growth and stability have been the central theme of Government policy since 2017 and even before.

During the 7 years of the current government’s term, this theme has been the driver of economic policy, communicated through the Budget & Economic Policy Statements of the Republic of Ghana since 2017.

Indeed the 2024 edition of the Budget Statement re-emphasizes the Government’s desire to stick with this approach to economic management. We are therefore convinced that a medium to long-term review of economic policy and performance would be a more accurate measure of Ghana’s progress towards the achievement of greater growth and/or stability.

Our review in this document therefore uses a balanced scorecard mechanism/approach to track Ghana’s economic performance guided by the Budget and Economic Statements for the 7 years. The KPIs for this review remain the following key indicators:

Economic growth and sectoral performance. Macroeconomic stability - inflation, exchange rates, interest rates, money supply, debt situation etc. - monetary policy in general.

Fiscal policy - revenues, expenditure (I.e. how we’ve mobilized revenue and how it has been spent). ✓ Infrastructure ✓ Social interventions Indeed, Paragraph 204 of the Budget Speech sets the tone for this exercise.

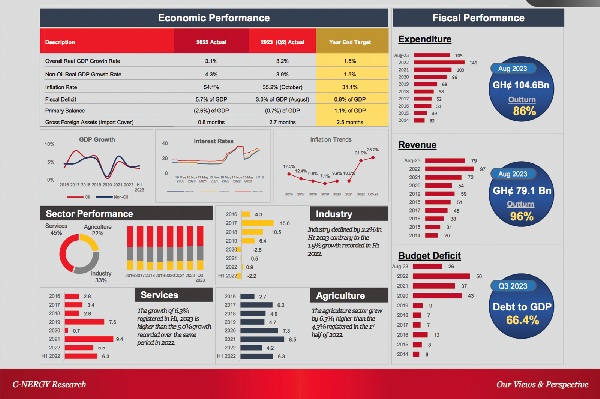

The Minister summarizes this in his Budget Speech, Paragraph 204, outlining the following achievements illustrated adjacent.

Our review interrogates these outcomes, using targets set in 2017, the key policy drivers and the results summarized above.

We provide an independent opinion with a time series analysis of the KPIs vis-a-vis global economic performance over the period.

Hitting the ghs 1tr mark – form over substance or real?

“From a nominal GDP of GH¢262 billion in 2017 to GH¢1 trillion in 2024”

Nominal GDP has certainly more than doubled from GHS262 bn in 2017 to over GHS 610 bn in 2022 in nominal terms and is projected to grow to over GHS 850 bn by the end of 2023. The forecast is that Ghana’s GDP will hit the GHS 1 tr mark in 2024 on the back of a modest 2.8% growth during the year.

Growth has been driven mostly by the services sector, accounting for more than 45% of total GDP within the period.

In Cedi terms Nominal GDP has grown at a compounded rate of 19% year-on-year between 2017 and 2022.

In USD terms however, Ghana’s nominal GDP has grown by less than 5% year-on-year. In 2022, nominal GDP in USD terms actually decreased from USD 79.14bn to USD 72.84 bn.

Additionally, the “rapid” growth in GDP has been driven principally by wholesale and retail trading (two elements representing the dominance of imports in Ghana’s economic activity).

Ghana’s GDP growth forecast of 2.8% for 2023 – 2024 that takes us to the GHS 1 tr mark is still significantly lower than the forecast for our peers like Cote d’Ivoire (7.1%), DRC (7.1%), Benin (6.1%), Kenya (5.8%).

Impactful quality access to education – a better use of resources

“Invested in the future of our children under the free SHS program with 1,261,495 students having access to secondary education.”

In 2017, the Government gave a clear signal of its desire and commitment to transform access to education as its major policy thrust with the introduction of its flagship free senior secondary education and free technical, and vocational education and training initiative.

The School Feeding Program has also been a major tool for driving pupil enrolment and attendance at the primary school level as well as mitigating child hunger.

The government has doubled the public expenditure on education from an average of GH¢20.7 billion,(2013-2016), to GH¢40.4 billion, between 2017 and 2020 (~95% growth) Ghana’s education budget has increased from GHS 11.3 bn in 2018 to GHS 24.8 bn in 2023.

Education’s share of total government spending has consistently fallen below the global benchmark of 20% (except in 2019) or the government’s own target of 23%. Education’s share of total government spending in 2023 will be 10.9%.

Since, 2018, the Ministry of Education (MOE) budget has increased by 120% in nominal terms, while prices of relevant goods and services have increased by around 170%, resulting in the education budget for 2023 being 18% lower in real terms than it was in 2018.

Per the 2023 medium-term economic forecast (MTEF), the Ministry of Education budget as a percentage of GDP is projected to continue falling in real terms until 2026.

There has been a fall in the prioritization of basic education in the Ministry of Education budget since the introduction of Free SHS such that basic education spending has dropped from 39.2% of the MoE budget in 2019 to 20% in 2023. Ghana’s education expenditure to GDP ratio of 2.9% is below the ECOWAS average of 3.6%.

Impactful quality access to education – A better use of resources

The School Feeding Program currently feeds 3.26 million pupils across the country while employing 32,500 caterers and the payment of professional and teacher trainees was restored in 2017. Since then, the percentage of trained teachers in primary schools has grown consistently from 55% in 2017 to 66% in 2021.

Since 2017, Ghana’s Human Development Index has grown by 3 percentage points from 60% to 63% since 2019 mainly due to higher educational attainment.

Seeing as primary education is already the most accessible, return on investment is likely to be reflected in the quality of education as measured by educational outcomes (results) and compared to enrolment statistics. Secondary school enrolment ratio has increased from 68.9% to 77.7% growing by 12.7%.

This is a direct result of increased accessibility, thanks to the Free SHS policy. Higher enrolment in secondary school translates into educational attainment which has driven improvement in Ghana’s HDI Score in the period under review.

The nominal growth in education expenditure is commendable but insufficient, given that the ratio to GDP of 2.9% is below the ECOWAS average of 3.6%.

To ensure a good return on investment and position Ghana as a net human resource exporter; like Cuba, India, etc. and one of few countries in the SSA region with highly-skilled human resources to support industrialization; a lot more investment is required.

Since the introduction of Free SHS, there has been a fall in the prioritization of basic education in the Ministry of Education budget. This is a dangerous trend and must be reversed because basic education has the widest reach/ accessibility and delivers significantly higher returns on investment than secondary and tertiary education.

Inequities in provision and per-pupil spending must be addressed as non-boarding SHS and TVET institute students receive significantly less funds per pupil than their counterparts boarding in SHS.

The gap can be closed by requiring parents to foot boarding fees while scholarships are made available to students that demonstrate financial need. This would free up funds to enrich the Free SHS program with more infrastructure while ensuring equity.

Distance with quality?

“Invested the most in the construction, rehabilitation and upgrading of major road networks across the country.”

Two major things guide Ghana’s infrastructure development plan: 1. Infrastructure Sector Management Programme; and

2. Human Settlement and Development Programme Ghana’s infrastructure development programme targets the development of quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure for economic development and well-being in order to meet certain Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Activities in the road sector in particular include Road Rehabilitation and Maintenance, Road and Bridge Construction and Road Safety and Environmental Impact Mitigation.

Since 2017, 103,971km, 66,133km and 30,278 of trunk, feeder and urban roads respectively have undergone maintenance. Between 2017 and 2020, 47,400km of trunk roads were earmarked for maintenance.

48% of the feeder roads targeted were covered, 75% of the target for urban roads was maintained and 96% of the trunk road target was achieved.

Within the period, 72,437km out of Ghana’s 78,000km+ of road network were maintained or constructed. 85,450km of feeder roads were targeted but only 49,073 were maintained within the same period.

The distance covered for urban roads for the same period was 4,900km less than the target. Several new roads and bridges have been constructed during the period.

They include 195km and 25km of trunk and urban roads in 2017, the construction of the Bridge on the Volta River at Volivo and Nsawam – Apedwa Road continued in 2018, the 3-tier Pokuase interchange under the Accra Urban Transport Project, the 3-tier interchange Tema Motorway progressed in 2019 and 2020.

Works were also completed on the Obetsebi Lamptey Circle Interchange and other ancillary works (Phase 1) in November 2020 and Phase 2 began in 2021. In 2022 and 2023, the La Beach Road Project among others commenced and is underway.

Since 2020, the feeder road network has recorded the largest variance in maintenance work. This must be addressed due to the direct impact on lead times for transportation of foodstuff and raw materials to cities, further compounding the ongoing inflation (food inflation especially) problem.

Distance with quality?

Some major national road development activities have also been targeted for financing, construction and management since 2017. They include 1. The Accra – Takoradi Road; 2. Accra – Tema Motorway; and 3. Accra – Kumasi Dualization project

The 3 major roads play a significant role in the transportation of goods and the movement of people. The Accra-Tema Motorway and the Accra-Takoradi road form critical parts of the N1 regional highway which connects Ghana to other West African countries.

Thus, the completion of expansion work on both roads will directly impact the smooth flow of goods and services on the Ghana stretch of the subregional road network. This is expected to have implications for Ghanaian businesses under the AfCFTA.

The Accra-Kumasi highway dualization project is incomplete after 6 years of construction despite the critical role played by the highway as the major connecting road between the southern and northern parts of Ghana.

Perennial delays in issuing payment to road contractors for completed work is the most cited factor dampening appetite for road investments in Ghana. Interventions such as road bonds, road tolls and aggressive Public Private Partnership hunting are needed.

The Government must strongly consider the BOO/BOT models of private sector participation in the provision of road infrastructure as is commonplace in developed countries like the USA. This would free up a significant portion of the Government’s expenditure spent on transportation infrastructure. Failure to move any of these major road networks from concept to completion over a 7-year period is an indication of a strain on resources available for infrastructure. There is a need for policies that attract private-sector intervention. The removal of toll booths has worsened the attractiveness of road financing to the private sector. It is obvious that the central government budget is not a reliable option for road infrastructure, given the country’s debt position and structural rigidities.

We are paying workers, but should that continue to be the priority?

Between 2017 and 2022, the Government’s wage bill grew by over 135% from GHS 25.9 bn to GHS 39.4 bn. The wage bill has taken up approximately 30% of total expenditure since 2017.

The ratio has dropped since 2018 from 33.7% to less than 23% as of August 2023. In the pandemic years of 2019/2020 compensation as a percentage of total expenditure was lower than the 2018 ratio of 33.7%. Approximately 7% of total

“Invested in making sure that all public workers were paid every month during the COVID pandemic including the teachers who were paid for all the nine months when the academic calendar was disrupted.”