Assessing the DDEP and fair value accounting impact on banks’ solvency

Although amortised cost securities are not affected by changes in market price any expected credit loss will be accounted in the loan loss reserves.

On banking sector outcomes, available indicators appear to suggest that the effects of domestic debt exchange operation overall could be unmanageable considering NPV estimated losses of the 23 banking institutions would impact negatively on regulatory capital.

Under the IFRS 9 or mark-to-market accounting can cause write-downs and regulatory capital problems for otherwise sound banks.

If these banks were to write down their assets to these distorted prices and, as a result, the bank’s regulatory capital could be depleted, the write-distorted prices and, as a result, the banks’ regulatory capital could be depleted.

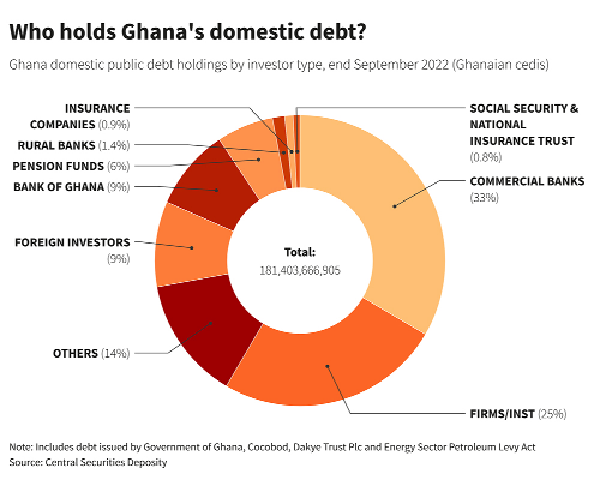

The central bank has recently attributed the decline in the industry’s capital adequacy ratio from 19 per cent to 16.6 per cent in December 2022 as the results of losses to mark to market investments, an increase in risk in risk weighted assets and the depreciation of cedi on foreign currency denominated loans but the estimated losses using of the NPV of local banks holdings could be negatively significant.

From the data analysis, we found that the estimated losses using the NPV of banking sector holding of government bonds and other notes could cause the depletion of regulatory capital adequacy ratios, followed critically by liquidity crunch, and decline in banks’ earnings and profitability, customers’ deposits run-down, and deterioration of quality of banks’ risk assets and reduction of banking activities in the area of lending to private sector and SME businesses.

Conclusion

Many have called for a suspension or substantial reform of fair-value accounting because it is perceived to have contributed to the severity of the recent domestic debt restructuring.

From data analysis, nine banks could be insolvent, while six banks would be solvent and eight banks would experience mild capital losses as a result of domestic debt exchange as well.

Based on our analysis and the evidence in the literature, we have little reason to believe that fair-value accounting contributed to Ghanaian banks’ problems in the domestic debt crisis in any major way but as a result of weak and lax risk management in the banks and regulatory failure in respect of Banks and Specialised Deposit Taking Act 2016 Act 930 (Section 62 (1) on limit on financial exposures.

Fair values

Fair values play only a limited role for banks’ income statements and regulatory capital ratios, except for a few banks with large trading positions. For these banks, investors would have worried about too much exposures in government bonds and notes, and made their own judgements, even in the absence of fair-value disclosures and weak risk management practices in the banking industry.

In sum, we believe that the claim that fair-value accounting exacerbated the crisis is largely unfounded but due to weak and lax in risk management practices as well as regulatory failures on the part of Bank of Ghana.

This implies that the case for loosening the existing fair-value accounting rules is weak.

Nevertheless, our conclusions have to be interpreted cautiously and should not be construed as advocating an extension of fair-value accounting, it is a call for improvement risk management practices in the banking sector as well as improvement in the regulatory framework.

We need more research to understand the effects of fair-value accounting in government bonds and notes to guide efforts to reform the rules.

One issue is that fair-value accounting loses many of its desirable properties when prices from active markets are no longer available and hence models have to be used, which in turn makes it very difficult to determine and verify fair values.

Thus, it is certainly possible that fair-value accounting rules and the details of their implementation could be further improved.

However, standard setters face many thorny trade-offs, several of which we discuss in greater detail in Laux and Leuz (2009).

First, relaxing the rules or giving management more flexibility to avoid potential problems of fair-value accounting in times of crisis also opens the door for manipulation and can decrease the reliability of the accounting information at a critical time.

One read of the empirical evidence on bank accounting during the domestic debt restructuring is that investors believed that banks used accounting discretion to overstate the value of their assets substantially.

The resulting lack of transparency and poor regulatory oversight about banks’ solvency could be a bigger problem in crises than potential contagion effects from a stricter implementation of fair-value accounting.

Downward spirals

Secondly, even if (stricter) fair-value accounting were to contribute to downward spirals and contagion, these negative effects in times of crisis have to be weighed against the positive effects of timely loss recognition.

When banks are forced to write down the value of assets as losses occur, they have incentives to take prompt corrective action and to limit imprudent lending in the first place, which ultimately reduces the severity of a crisis.

A central lesson of the 2017 -2018 Ghanaian banking crisis is that when regulators hold back from requiring financial institutions to confront their losses, the losses can rapidly become much larger.

For the same reason, it is problematic if accounting rules are relaxed or suspended whenever a financial crisis arises because banks can reasonably anticipate such changes, which diminishes their incentives to minimise risks in the first place.

If the goal is to dampen pro-cyclicality, it may be more appropriate to loosen regulatory capital constraints in a crisis than to modify the accounting standards, as the latter could hurt transparency and market discipline.

Recommendation

As policy strategy to eliminate shortfalls in bank capital has to be carefully designed to ensure financial stability while limiting fiscal risks, which is particularly difficult during a debt restructuring.

Shortly after the domestic debt restructuring, Bank of Ghana should require viable banks that are likely to need recapitalisation to develop a credible plan to restore compliance with capital requirements and buffers over a reasonable period of time, with close supervisory oversight of the implementation of these plans.

In some jurisdictions such as Greece, public sector recapitalisation or other state support for banks may be considered as a last resort to maintain financial stability and avoid disruption to the real economy, but this may offset part of the debt relief targeted through the domestic debt exchange.

If this is the case, additional debt relief may need to be obtained from the sovereign’s other liabilities.

Leveraging a well-designed framework for bank resolution, resolution funding, and deposit insurance could help mitigate risks to financial stability, but contagion risks tend to be higher in debt restructuring cases where credible public sector guarantees, and funding backstops may not be available.

Gaps in crises

Bank of Ghana must identify gaps in crisis management and bank resolution frameworks should be identified prior to the domestic debt exchange programme.

Gaps in early intervention, resolution, deposit insurance, and central bank liquidity assistance for which Bank of Ghana in the process of establishing Financial Stability Support Fund as well as the coordination arrangements among these elements should be addressed before the Domestic Debt Restructuring.