Domestic debt restructuring: Successful programme key to external negotiations

Analysts at Standard Bank say government’s ability to access the US$3 billion IMF bailout hinges on the successful conclusion of its domestic debt exchange programme (DDEP).

The government has said it required at least 80 per cent sign off of all the domestic debt of Gh¢137 billion to qualify it to reach a threshold of 55 per cent debt to Gross Domestic Product (GDP), a condition that will trigger the IMF bailout.

However, there has been growing concerns from individual domestic bold holders, financial insitutions and some institutional investors about the government’s proposed haircut on domestic bonds.

Government engagements with various stakeholders are bearing fruit as the financial services sector has agreed a roap map for DDEP paving the way for the government to be optimistic about its programme as the deadline approaches on January 31, 2023.

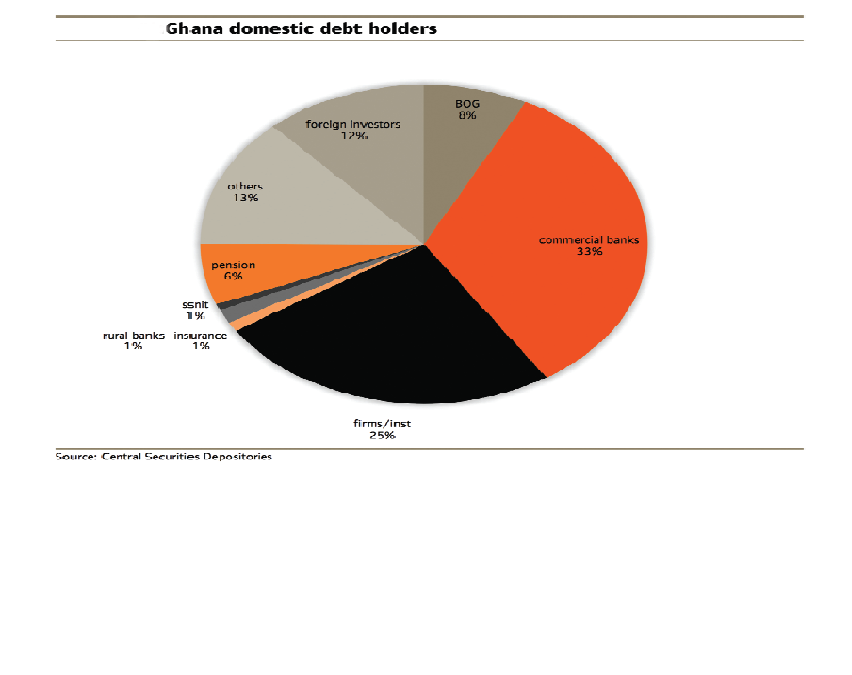

Data from the Central Securities Depository, indicate that foreign investors account for 12 per cent of the country’s domestic debts, the Bank of Ghana (BoG) has eight per cent; commercial banks, 33 per cent; pensions have six per cent; Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT),one per cent; rural banks one per cent, insurance firms, one per cent; firms and institutions,25 per cent and others,13 per cent,

Although the government managed to secure a staff-level agreement last December with the IMF, it is not clear what the next steps are as it struggles to convince individual domestic bondholders to accept a haircut.

Earlier in the week, the government managed to get the banks in the country to agree to sign onto the programme with other financial and non-financial institutions awaiting to come on board.

As it stands now, the government is seriously racing behind time to complete the voluntary programme by the end of this month.

It is expected to have at least 80 per cent approval before it can proceed to the next stage of accessing the IMF funds.

The most critical part of the entire development is the fact that funding under the IMF programme may also prove the catalyst for other multilateral partners to extend budget support to Ghana, similar to what has pertained to other IMF programmes in Africa.

The ARM report is of the view that once a staff report from the IMF is published, it may become clearer what level of domestic debt is needed to be restructured and what external debt haircut is expected to restore debt sustainability.

Debt vulnerabilities

In spite of Ghana’s huge debt, it is looking forward, just like many other African countries in debt distress, to having access to the international capital markets.

This is crucial for the country in view of the fact that last week, the BoG confirmed that the country’s foreign exchange reserves were in the red because it now stands at just six weeks of import cover and still reducing.

The ARM report said debt vulnerabilities for some economies were compounded in 2022 following the rise in geopolitical tensions and steep increase in interest rates in advanced economies.

The tighter monetary policy conditions, which triggered capital outflows from Africa, not only resulted in fiscal funding shortfalls but also exacerbated balance of payment (BOP) pressures.

Indeed, it is projected that many African economies have used external funding sources from international capital markets to boost FX reserve buffers over the better part of the last decade. Thus, there were inevitably going to be enhanced external account pressures in 2022.

Over the coming year, some African governments may tap into international capital markets again from the first half of the year or even earlier for some, although the underlying debt vulnerabilities may remain.

The ARM report observed that just barely a week after the authorities and the IMF reached a Staff-Level Agreement (SLA) for a three-year $3.0 billion external credit facility (ECF) arrangement, Ghana officially suspended repayments for its Eurobonds, other commercial debt and most bilateral debt too on December 19, 22.

Debt exchange

It said multilateral creditors had been excluded for now. The authorities also proposed a voluntary domestic debt restructuring programme for GHS bonds, with an initial deadline of December 19, 22, which has now been extended for a third time, to Jan 31.

The initial proposal on offer looked to exchange existing government bonds into four new bonds that will mature in 2027, 2029, 2032 and 2037. Furthermore, coupons on these new bonds will be halted in 2023, before rising to five per cent in 2024 and then 10 per cent from 2025 until maturity.

Notably, the authorities opted for an extension of maturities and reduction of coupons rather than a haircut on principal to ensure a limited negative impact on the capital positions of the local banking sector.

Doubt lingers

However, the report said with domestic debt restructuring being voluntary, there were admittedly growing concerns on whether the government could secure an adequate amount of local debt to be restructured to appease the IMF and external creditors but, more importantly, commence the journey towards achieving debt sustainability.

The government has already excluded pension funds.

The ARM estimates that the government would have to restructure at least 50 per cent to 60 per cent of the local debt.

The report notes that authorities have indicated that they are in talks with the World Bank to potentially arrange a financial sector stabilisation fund of around $1 billion, to ensure that financial sector stability is not derailed during the debt restructuring process.

But still, as already seen by the postponement of deadlines over the past month or so, domestic debt restructuring may prove complicated for the government.

Admittedly, the report suspects that IMF executive board level approval for the USD3.0 bn programme will mostly be contingent more on domestic debt restructuring progress than progress on the external side.

Conclusion

However, the report is of the view that the government is expected to restructure external debt under the G20 common market framework, which, arguably since inception, has not been swift enough in finalising debt restructuring for countries such as Zambia and Ethiopia (which are still in discussions with external creditors).

Yet, some cautious optimism does arise given that, for instance, in Zambia’s discussions, there is emerging consensus that China’s influence as the single largest bilateral creditor may be delaying negotiations on a debt restructuring deal, which Ghana may not struggle with due to smaller holdings of external debt by China.

Still, a successful domestic debt restructuring may be a prerequisite for external debt restructuring negotiations to progress well and thus for improving the chances of getting IMF executive board-level approval sooner in the second half of the year.

The report believes that funding under the IMF programme may also prove the catalyst for other multilateral partners to extend budget support to Ghana, similar to what has been witnessed with other IMF programmes in Africa.

Yet, once a staff report from the IMF is published, it may become clearer what level of domestic debt is needed to be restructured and what external debt haircut is expected to restore debt sustainability.

The analysis proves clearly that in the end, there is a need for some burden sharing among all and sundry, including the government, groups and individuals as the clock fast ticks.