e-Cedi: Finding balance between financial stability, regulation, consumer freedom and privacy rights

Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) have emerged as a significant topic of discussion in several developed countries including the United States of America. 19 of the Group of Twenty (G20) countries are contemplating issuing CBDCs, with many having progressed beyond the research phase.

According to a Bank for International Settlements (BIS) survey in 2021 on CBDCs, 86% of central banks are actively researching their potential, with 60% experimenting with the technology and 14% deploying pilot projects.

The number has since increased to 93% of central banks engaged in some form of CBDC work as of 2023.

The Bahamas was the first country to issue a CBDC— the Sand Dollar—while China's e-Yuan offered via the Digital Currency Electronic Payment (DCEP) platform is the most widely used CBDC presently.

The Bank of Ghana last year announced a postponement of the launch date of its central bank digital currency the e-Cedi, from 2024 to 2026, citing unfavorable timing amidst recent economic turbulence.

Interestingly, discussions with individuals ranging from everyday citizens to professionals within the financial services industry reveal a notable lack of awareness or understanding regarding the significance of e-Cedi.

The prevailing sentiments revolve around questions like: “What is a CBDC?,” “Is it necessary?” and "How does it differ from the digital version of the cedi already widely used through platforms like Mobile Money, internet banking, and banking apps?"

A CBDC is merely a digital version of an existing national currency, secured by blockchain technology.

The main differences between CBDCs and digital payments such as mobile money is that whereas CBDCs are new instruments created to coexist with fiat currency or replace currency, mobile money is not a new instrument but a type of payment for transactions based on existing currency. Mobile money utilizes existing mobile money operators’ infrastructure to manage customers’ wallet balances based on various transactions.

In a nutshell, CBDCs are central government issued and controlled and are to be transacted via traditional financial institutions with central bank oversight. This makes CBDCs different from existing private digital currencies.

Privately issued cryptocurrencies have been around for the last 16 years following the publication of the Bitcoin whitepaper during the global financial crisis in 2008.

Cryptocurrencies claim to provide a reliable medium of exchange independent of central bank manipulation, thereby offering greater potential as a store of value, coupled with unparalleled mobility and speed.

CBDCs v. Cryptocurrencies in Africa

The Central Bank of Kenya recently ordered commercial banks to temporarily close accounts of customers with recent cryptocurrency transaction history and apply exorbitant exchange rates to cryptocurrency transactions.

The Bank of Ghana has clarified that cryptocurrencies are not legal tender in Ghana but has refrained from taking formal regulatory action beyond banning direct debits /credits between cryptocurrency exchanges and commercial banks and monitoring Mobile Money accounts of suspected cryptocurrency dealers.

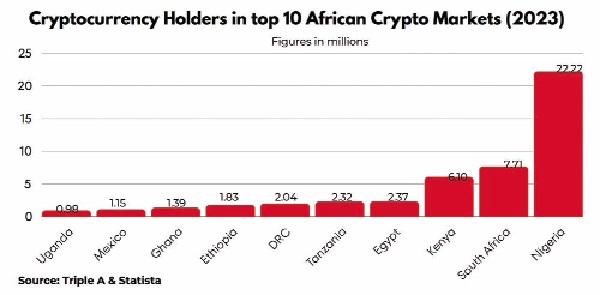

Nigeria is the largest cryptocurrency market in Africa (fourth largest globally, behind only Pakistan, India, and the US) with more than 20 million cryptocurrency holders and an accelerating rate of adoption. Nigeria is arguably the most hostile to cryptocurrencies.

The Nigerian government declared cryptocurrencies illegal in 2021. Commercial banks were ordered to abstain from cryptocurrency transactions. In March 2024, the popular cryptocurrency platform Binance became the forex hotspot in response to new central bank restrictions on forex sales.

Nigerian authorities allege that speculation on the Naira on Binance was the main driver of the free- fall of the Naira against the US Dollar in Q1 2024.

In response, the company was fined US$10bn and two executives of Binance were detained by the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) and charged with operating a cryptocurrency exchange which is an unlicensed business.

Regulatory attitudes and responses

In 2022, more progressive countries like South Africa begun licensing cryptocurrency businesses and recognized cryptocurrencies as legal financial assets and financial products.

The Central African Republic designated cryptocurrencies as legal tender in 2022.

Countries such as Egypt, Morocco and Tanzania have largely maintained a hands-off approach to cryptocurrency activities neither restricting adoption nor introducing regulations, an approach considered moderate.

Ghana, Kenya, and Nigeria seem to be on the hostile end though Ghana and Kenya have hinted at introducing comprehensive regulations for digital/cryptocurrencies in the future.

The central banks of Kenya and Ghana periodically issue cautionary notices to the public pertaining to cryptocurrencies. These notices have been more frequent following the rapid adoption of cryptocurrencies post-pandemic.

Further, the EFCC is currently seeking comprehensive data of all Nigerian users of the exchange platform in order to investigate them for money laundering and terrorism financing.

CBDCs as secure and trustworthy alternatives to privately issued digital currencies

In total, there are 13 CBDC projects in Africa. 11 are currently active. The projects in Egypt and Senegal are inactive.

This is mainly to reinforce central bank control over the supply and circulation of money in the digital age.

Nigeria was the first African country to launch a CBDC, the e-Naira in 2021. The Central African Republic launched its CBDC-the Sango Coin in July,2023.

CBDCs are being piloted in South Africa, Mauritius, and Ghana to ostensibly overcome the challenges of existing payments infrastructures and give tech companies and startups in the e-commerce/fintech space, a digital standard platform for further innovation.

Kenya, Rwanda and Eswatini have disclosed intentions to explore CBDCs.

Thus, African central banks’ stated objective of addressing the risk associated with unregulated privately issued digital currencies with CBDCs is in full force. So long as private sector cryptocurrencies remain available there is no reason for criminals to use CBDCs.

Simply not a “good enough” substitute for private cryptocurrencies due to centralization and vulnerability to central bank manipulation via monetary policy.

These are among the risks citizens of developing countries seek to address with the adoption of privately issued cryptocurrencies in a climate of macroeconomic instability and low confidence in financial systems.

Consequently, efforts to shut down adoption of private virtual assets (cryptocurrencies) while promoting CBDCs as the sole alternative to cash seem destined to fail in struggling African economies in the medium term.

The table below shows major African economies that have suffered debt crisis, hyperinflation, or economic recession since 2020 and their global rank in terms of crypto adoption and peer-to-peer crypto trading.

The high adoption is likely due to these economies being relatively wealthier and with more robust financial systems that support alternative financial products such as crypto.

Citizens have relatively higher disposable incomes and sophistication to dabble in riskier financial products.

The realization of the anti- terrorism and money laundering benefits of CBDCs therefore hinges on the strict enforcement of a complete ban on all privately issued cryptocurrencies.

This probably explains why central banks of the most vulnerable countries are scrambling to launch CBDCs to complement total bans on the use of privately issued virtual assets once CBDCs are successfully rolled out.

Identity-verified cryptocurrency users

Practically, the challenge with enforcing such a ban is the obvious problem of stopping a technology with a significant and growing adoption rate estimated at 175%

p.a.

The cryptocurrency adoption S-curve is estimated to be on the brink of the early majority stage.

An equivalent technology for comparison purposes would be what became the internet in the late 1990s. The chart adjacent shows the rate of adoption of cryptocurrencies.

A complete ban is likely to be counterproductive as evidenced by Nigeria's experience where crypto adoption has only grown exponentially since the official ban in spite of the e-Naira.

The e-Cedi

Essentially, the e-Cedi is a retail token-based central bank digital currency which the Bank of Ghana envisions as a value-based approach, akin to a digital value note.

Transactions would involve transferring this value note from one party to another, resembling cash payments where banknotes and coins change hands.

To highlight its objectives and functionalities, the Bank of Ghana released an introductory document titled "Design Paper of the Digital Cedi (e-Cedi)" in 2021.

This document underscores the BoG's commitment to promoting innovative and accessible digital financial services aimed at expanding financial inclusion and fostering the adoption of digital payments as a viable alternative to cash.

Moreover, mainstreaming digital payments is anticipated to formalize the economy, thereby enhancing the efficiency of fiscal operations and monetary policy transmission mechanisms.

The BoG anticipates the e-Cedi's role in enhancing operational efficiency and cost-effectiveness in payments, as well as providing a secure and trustworthy alternative to privately issued digital currencies.

The BoG aims to achieve the following strategic objectives with the introduction of the e-Cedi:

Increase digitization within the Ghanaian economy. Foster financial inclusion and encourage consumer adoption of digital payments.

Position the BoG as an active regulator and facilitator of a digital economy.

Enhance the security, efficiency, and resilience of the payment system.

Mitigate the risks associated with unregulated privately issued digital currencies or virtual assets.

The core principles guiding the e-Cedi's design which are Governance, Accessibility, Interoperability, Infrastructure, and Cybersecurity, have been represented in the following design features:

Programmable use cases include "government-to- person" and "person-to-government" payments, as well as "machine-to-machine" automated payments on the Internet of Things.

Designed for interoperability with CBDCs of other jurisdictions, particularly those within the AfCFTA and ECOWAS frameworks.

Integration into existing interbank payment systems and mobile money interoperability platforms operated by the Ghana Interbank Payment and Settlement Systems Limited (GhIPSS).

High-trust infrastructure capable of handling large transaction volumes, providing 24/7 availability, and supporting instant payments. Separation of currency issuance and distribution modules mitigates cyber risks, ensuring high security standards.

High-speed transactions, facilitating near-instant fund transfers that are easy to confirm and traceable. Highly accessible, functioning effectively in both online and offline environments to accommodate areas in rural Ghana lacking mobile data networks.

The e-Cedi & financial crime reduction

According to the e-Cedi Design Paper, the BoG aims for transaction transparency to be balanced with consumer data privacy while remaining fully compliant with Know

Your Customer (KYC) and Anti-Money Laundering/Combating the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) regulations. Financial institutions will monitor e-Cedi transactions and report suspicious activities to the Financial Intelligence Center (FIC).

The BoG will define ecosystem participation policies covering wallets, transaction limits, monitoring, regulatory compliance, and sanctions for breaches.

This indicates the e-Cedi's role in the BoG's efforts to combat money laundering, terrorism financing, and other illicit financial activities.

The feature of the e-Cedi which is the focal point of this article is its Traceability. Utilizing blockchain technology, all transactions conducted with the e-Cedi will be permanently recorded on a ledger, ensuring immutability of important traceability records.

With digital currencies built on blockchain, once information is entered into the shared system, it becomes unchangeable, creating an unbroken chain of transactions readily traceable at any point.

Though cryptocurrencies are pseudonymous since transactions in the public ledger are represented by cryptographic addresses rather than personal information, ownership of wallets is easily uncovered with KYC records.

Additionally, personal information of transacting parties captured by wallet registration KYC records, integrated with national identification systems, further enhances traceability.

Transactions cannot be hidden or altered without alerting all users in the system. Consequently, the traceability of the e-Cedi is expected to presumably aid in combating the use of private cryptocurrencies for criminal activities such as money laundering and terrorism financing.

Surveillance & weaponisation risks of CBDCs in a cashless economy

Despite the BoG's noble intentions for combatting financial crimes using CBDCs, there are inherent surveillance risks for the ordinary citizen.

The impending rollout of CBDCs has met resistance in parts of Europe and Asia for this reason.

In September 2023, the US House Financial Services Committee passed a bill that would prevent the Federal Reserve Bank from issuing a CBDC.

This action followed the introduction of the CBDC Anti-Surveillance State Act Bill which is currently awaiting a congressional vote.

The bill has garnered support from 60 Congress members who are concerned that CBDCs, including the digital dollar, could jeopardize citizens' financial freedom and privacy rights as it lacks features of cash such as openness, permissionless and privacy attributes.

CBDC skeptics are primarily concerned about the state having complete control over a digital version of the national currency in a cashless regulatory environment that prohibits stable coins (private sector alternatives pioneered by cryptocurrency industry.