Stratification of Africa requires appropriate policy choices

In November 2010, Ghana rebased its gross domestic product (GDP) and instantly, the economy expanded by about 60 per cent , mainly by applying higher indexes to services and construction.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), African Development Bank (AfDB), and development partners (DPs) use this income classification to make decisions on tapering or stopping grants and concessional loans to low-income countries (LICs).

In November 2011, Ghana consolidated its MIC-status with exports of about 70,000

This later “gas-to-power” strategy involved the construction of offshore pipelines, a processing plant, and other infrastructure.

This ‘self-financing’ facility,

The

Transition blueprint

From 2012 to 2016, certain factors adversely affected Ghana’s per capita income and growth rates but its MIC status remained.

They include the 2010 census increasing the population by 30.4 per cent (18.9 to 24.7 million); Nigerian gas supply disruption (2012 to 2015); fiscal slippages from subsidies and wages; and the continuing global crisis leading to slowdown in emerging market demand and sharp falls in prices for exports – gold, cocoa, and crude oil.

Ghana and other Sub-Saharan African (SSA) MIC states survived the downturn but a transition plan could help the ensuing economic recovery and

These MIC and resource-rich (RR) states need to improve and sustain economic performance, in Ghana’s case managing additional crude supplies from the TEN and Sankofa fields from 2017.

The projected growth of 6.5 to 8

The consolidated MIC-status will entrench the country’s exposure to the capital markets.

Ghana and other SSA states such as Kenya, Mozambique, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, and Uganda expect to get more incomes from new natural resource flows.

SSA ‘stratification’

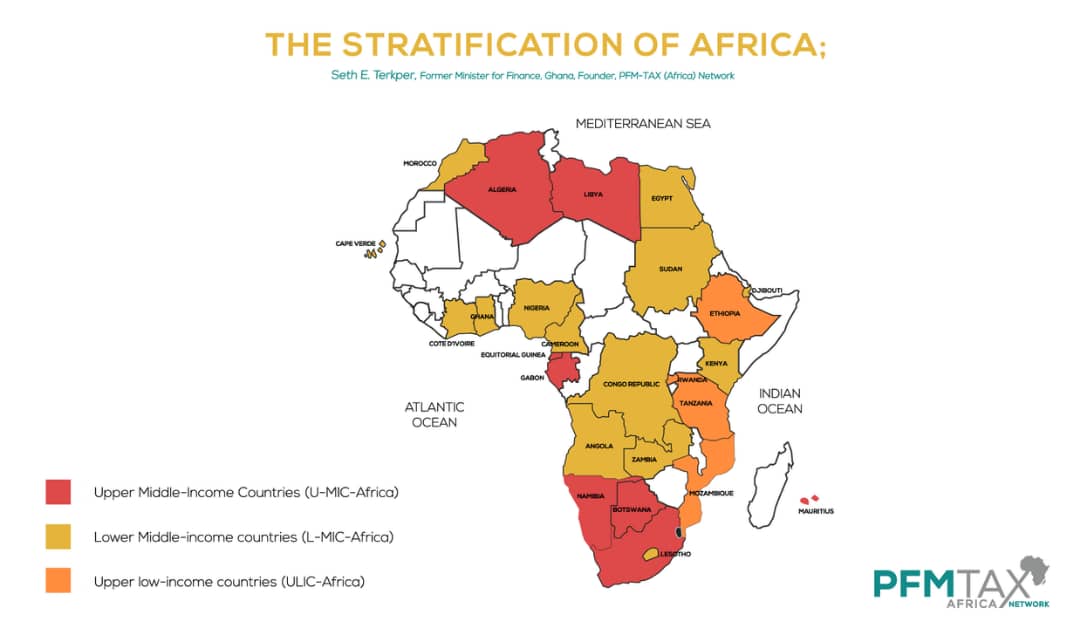

The World Bank’s 2018 Atlas on Gross National Income (GNI) and per-capita income draws attention to Africa’s gradual stratification and need for ‘tailored’ plans to improve performance (www.worldbank.com).

The groups are low-income economies with per capita income of US$1,005 or less; lower middle-income (LMI) with US$1,005 to $3,955; upper middle-income (UMI) with US$3,956 to US$12,235; and high-income economies above US$12,236.

We add an unofficial upper low-income group (US$600 to US$1,004) and note that Seychelles is the only high-income SSA state.

1.

2. Lower Middle-income countries (L-MIC-Africa): Angola, Cape Verde, Cameroon, Congo Republic, Cote d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Mauritania, Morocco, Nigeria, Sudan and Zambia.

3. Upper low-income countries (ULIC-Africa): Ethiopia, Mozambique, Rwanda, Tanzania

4. Low-income countries (LIC): The remaining states fall below US$1,005, with focus on poverty alleviation and managing fragilities from shocks (e.g., unstable commodity prices and disaster (e.g., wars, earthquakes

MIC-Africa must avoid the ‘MIC trap’ that affects many Caribbean, Eastern European, and Latin American states with integrated transition

Africa Rising

As Deputy and Minister for Finance from 2009 to 2016, I participated in Africa Rising or Renaissance events on SSA ‘Lions’ with high growth rates of five-to-seven

It was due to rising BRIC demand and high commodity prices, new natural resource finds, access to emerging market funds, and, some argue, gains

The fall in demand and price bubble from 2015 got worse with domestic factors. Ghana’s growth rate fell gradually from a peak of 14

Although tamed by the global downturn, about nine SSA ‘Lions’ kept their MIC status, despite the tough financial market conditions that worsened borrowing costs and economic performance.

At the height of the ‘rising’ debate,

However, there was no MIC transition blueprint to serve as input for the Home-Grown Policy that was used to negotiate the IMF ECF Program in 2014. As

Policy choices

Some MIC-Africa

A key element is

Revenue

SSA’s pioneer autonomous revenue authorities (RAs) in MIC states must (a) enhance tax audit and compliance methods; (b) use electronic processing and data-gathering options

Budget spending and deficits: The World Bank’s Integrated Financial Management Information Systems (IFMIS) reforms must have;

a) budget responsibility laws to curtail the latitude that leads to budget overruns;

b) improved treasury and cash-flow methods for revenues held in central and commercial bank accounts;

c) semi-accrual accounting processes under IPSAS principles to shift from the narrow definition of ‘arrears’; and

d) public investment or contract databases—to curb unplanned deficits from ‘unfunded’ expenditure mandates that breach budget guidelines and Estimates.

Borrowing and debt management: Setting up specialized Debt Management Offices (DMOs) to;

a) control unplanned borrowing through proper targeting of capital expenditure, as distinguished from liquidity;

b) Refinance short-term debt used in support capital projects not covered by commercial or concessional borrowing;

c) Separate liquidity budget needs from long-term loans as part of the development of domestic capital markets.

Secondary market tools: invest natural resource flows in market tools such as sinking funds, buy-backs, and soft-amortization to alleviate the risk of debt distress or default from frequent "roll over" interest-only "bullet” loans or bonds.

Self-financing commercial projects: As MIC-Africa loses concessional loans and grants, it must find alternatives to “sovereign guarantees” that crystalize automatically into pure public debt—through market-friendly options such as self-financing schemes that use commercial projects revenues in dedicated debt service accounts to repay loans; and infrastructure (investment) funds to leverage borrowing from capital markets.

These examples are not exhaustive but highlight an integrated approach to managing budgets to achieve better fiscal outcomes. The solution to the risk of debt

They must form part of the SDG’s Finance for Development (

Further, MIC transition plans must include real sector growth strategies, such as Ghana’s “gas-to-power” plan for improving power supply for industry and services. Despite the agricultural and natural resource view of the country, it is the Services sector that has grown rapidly and constitutes, on average, 49-to-51 percent of GDP.

The main drawback to the absence of MIC transition strategies is a uniform view that appears to ignore the gradual “stratification” of SSA states and

A focus on potential Lions in

Africa needs to take the initiative, to formulate and implement “tailored” plans, with the assistance of multilateral and other development agencies. An example is the AfDB assistance to Ghana in preparing its original Home-Grown Policy in 2014.

Saying that the graduation to MIC status is a meaningless statistic is not enough: it has real fiscal, financing and development impact in countries across

The writer is a former Finance Minister and founder, Tax Policy Africa, a public finance accounting firm based in Accra

email: