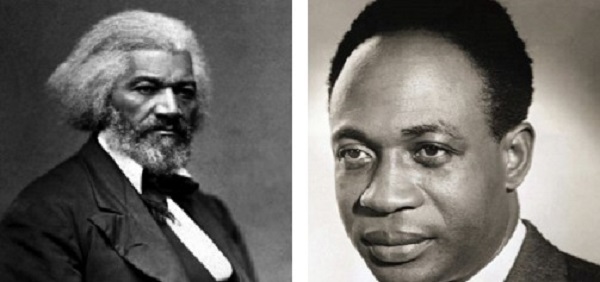

Tale of two giant freedom fighters - Fredrick Douglass and Kwame Nkrumah

Cycles in history tend to be incited by the personality and vitality of leading figures who captured attention to showcase the mood of the times.

In particular, the history of the struggle against racial injustice and colonial exploitation can name a wide range of activists, but two iconic personalities who led the struggles respectively were Frederick Douglass – in the United States, and Kwame Nkrumah – in Africa.

Those two giants were, without question, the great trailblazers in their times.

Articulate, undaunting, tenacious, it was a wonder how the world would have been for black people without those two exemplars.

They set the tone for the foundation on which to build understanding and unity among people of African descent.

No wonder they were despised by the powers that be in their times.

Born into slavery around 1818, Frederick Douglass — for one — became a key figure in the abolitionist movement against slavery.

He taught himself to read and write using the Bible.

On July 5, 1852, in Rochester, New York, he gave a fiery speech titled, “What to the Slave Is Your Fourth of July?” to address the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society.

He said the following:

Frederick Douglass

“I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us.

The blessings in which you this day rejoice are not enjoyed in common.

The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity, and independence bequeathed by your fathers is shared by you, not by me.”

“The sunlight that brought life and healing to you has brought stripes and death to me.

This Fourth of July is yours, not mine.

You may rejoice, I must mourn.

To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony.

Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak today?”

“What, to the American slave, is your Fourth of July?

I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days of the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is a constant victim.

To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy licence; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciation of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade and solemnity, are, to Him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy — a thin veil to cover up crimes that would disgrace a nation of savages.

There is not a nation of the earth guilty of practices more shocking and bloody than are the people of these United States at this very hour.”

“At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed.

O! had I the ability, and could reach the nation’s ear, I would, today, pour forth a stream, a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke.

For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder.

“We need the storm, the whirlwind, the earthquake.

The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and the crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.”

Kwame Nkrumah

On July 1, 2007, watching the African Union deliberations on television, I couldn’t help but note the absence of Nkrumah’s glow of conviction and earthy confidence.

His absence at that forum was so conspicuous that to not have witnessed his presence was like missing the giant in the room.

Without Nkrumah, his magnificent persistence, energy, and consistency were lost to the meeting.

Lacking the rallying focus, and bereft of inspiration, the participants – adorned in magnificent robes and designer suits - flurried about the conference centre isolated and individualistic like orphans begging the arrival of the heroic father figure.

It was clear then and today that when the massive personality exited the scene things were never quite the same again.

The gaping vacuum on the African front did not just happen.

The lack of a governing consensus or a vital centre in African affairs these days revealed as much about many of the current leaders themselves just as the ostensible neo-colonial power mongers.

Since Ghana’s independence from British rule in 1957, I have seen Africa’s leaders of various stripes come and go.

But any way you sliced it, Nkrumah towered head and shoulders in purpose and commitment.

And one is compelled to ask what set Nkrumah so much apart from the rest.

For one thing, Nkrumah’s impressionable years, university education and experiences in America had a lot to do with it.

The racially explosive 1930s and 1940s of racist Jim Crow laws in America exposed him to hardcore white racism, slavery on the plantations, and the strange fruits of lynchings of Negroes in the American south.

Returning home to the Gold Coast, he saw another heart of darkness in the poverty and misery of the African masses caused by a weird mix of imperial colonialists, fiefdoms, religious reactionaries, and a comfortable local elite with little concern for their fellow men.

He said so himself and was determined to do something about it.

The rest of that history needs to be taught as matters of urgency.

The writer is a trainer of teachers, leadership coach, motivational speaker and quality education advocate.

E-mail: