The just ended voters registration exercise and the controversial discussion of the appropriateness of a birth certificate (BC) in getting a voter card has brought into sharp focus the issue of who really a Ghanaian is.

The question is not easy to answer. It has been widely discussed in the media in the lead-up to the registration exercise and continues to date.

Many experts have discussed it, especially, after the Supreme Court (SC) ruling. What I intend here is to consider the issue of citizenship in a wider perspective than that of constitutionalism and how other countries handle the problem.

The five articles of Chapter Three of the 1992 Constitution define who a Ghanaian is. But that does not end the discussion.

There are matters of interpretation of those articles and these are not simple. The Supreme Court, the body vested with interpreting this constitution, may make a ruling on it, but even that will not resolve the issue – at least not in the popular imagination.

Philosophical dimension

Quite apart from the provisions of the Constitution, the issue has a wider philosophical dimension. Who is ‘really’ a Ghanaian? Our nation, Ghana, is an artificial concoction of disparate entities forced on us by colonialism.

The problem we are facing today with deciding who a citizen is, is just one of those faced by the post-colonial state.

Not even a written constitution can adequately capture the citizen in a situation where the state is not a natural entity.

Ghana was made up, at independence, of four separate units: the Gold Coast colony proper, the Ashanti Kingdom, the Northern protectorate and Trans-Volta Togoland. Each of these could have been a state on its own.

Each came under British influence at different times, but came together as equal partners, to constitute the state of Ghana on March 6, 1957.

Without colonialism, we would have had other entities that are more homogeneous than the sum of the four units that make up present Ghana.

The Independence Constitution ensured that citizens of all the entities became equally Ghanaian. No citizen of any of the erstwhile entities can, therefore, claim to be more Ghanaian than a citizen from another erstwhile entity.

Artificial

The artificial state we have now is a fait accompli. Nobody is going to divide Ghana. But the effects of the colonial order are still being felt by us today.

All along the borders of Ghana are people who belong to tribes or communities that stride these borders.

These people have interacted among themselves long before the white man came to divide us, leaving us with the amorphous entity called Ghana.

The Constitution defines citizenship, but the reality on the ground can never be adequately captured by constitutional provisions.

What do we do? We try to draw the line of citizenship somewhere and interpret the Constitution to accommodate it.

Jean Mensa, the chairperson of the Electoral Commission (EC), has chosen to draw that line, for the purposes of the next elections, at a place that excludes the use of a BCs as proof of citizenship.

And the SC agreed with her. We do not, as yet, know the full consequences of this action.

I wish to argue that even agreeing on where to draw the line of citizenship will not solve our problems. This is because our problem is basically a logistical one.

We simply do not have the means to make a proper count of our citizenry no matter how we define that citizenship.

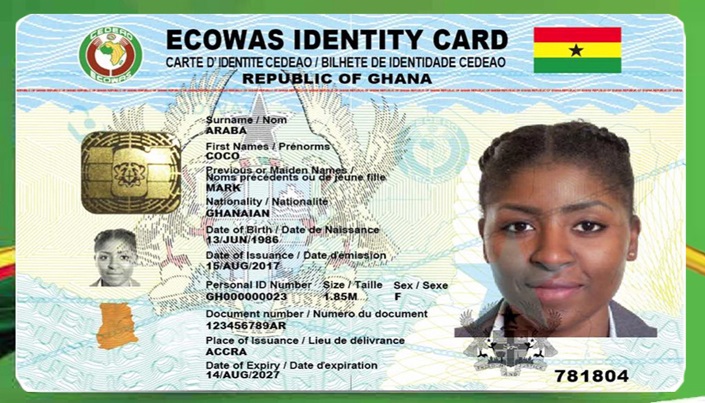

The Ghana Card is supposed to solve this problem once and for all but it is, itself, beset with the same intractable problems we are facing now.

A proper count of our citizens, well documented, will solve all our problems forever. But can we do that?

Consideration

This brings me to a consideration of the issue as dealt with in other countries. I have lived in both Sweden and Finland for the past 35 years. I went there as a student and for all the years there, I had never registered to be able to vote.

Yet I always voted in every single election in the countries during my stay. These two countries, and others like them, do not conduct censuses or voter registrations, because at every moment in time, the personal details required in these exercises are already known by the relevant authorities.

Everyone born is given a 10-digit personal number at birth (social security number based on date of birth), which is unique to him or her until they die.

All foreigners in the country are also issued this number on the day they become legal residents. With the number, the authorities know everything about you, including your status as a voter.

At election time, they just dig into this database of citizens and residents and send letters to all eligible voters inviting them to vote.

This letter indicates the votes you are entitled to, where to vote and at what times. You do not have to travel to your home village in order to vote for the candidate in that area, since postal voting is allowed from two weeks to the Election Day.

With such a system, there is no way anybody can sneak into the country to try to register to vote. It all looks so simple and so easy. But it was long in coming. These countries have been counting themselves since 300 years back.

How far are we from this idyll? This is what the electronic Ghana Card is supposed to lead us to. But can we get to that stage? Your guess is as good as mine…

The writer is the author of Dark Faces at Crossroads

Email: stephen.owusu@email.com