Desalination: A beacon of hope in looming water crisis in Ghana

Despite the Earth's vast expanse of water—a staggering 71% of its surface—our global community grapples with a challenge: the accessibility of safe drinking water is alarmingly inadequate.

With a reservoir of 332.5 million cubic miles, equivalent to over forty-eight billion gallons per person, one would assume an abundance of this life- sustaining resource.

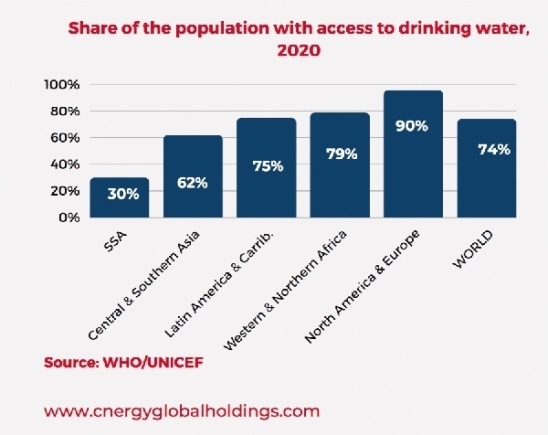

However, the studies reveal a different narrative. One in every three people struggles to access clean drinking water.

Delving deeper, we uncover a startling revelation: a mere one per cent of Earth's water is suitable for consumption. The remainder—97% salty and 2% locked in glaciers or hidden underground—leaves humanity with a precarious balance between plenty and scarcity.

In this narrative, the global water crisis emerges as a pressing concern, casting a shadow over the perception of abundance and underscoring the urgent need for solutions.

The abundance of unsafe water for human consumption is causing a global water crisis, especially in Africa, where millions of people do not have access to clean water.

Experts say that by 2050, more than half of the world's population might live in areas where there is not enough water. This is potentially a big problem. Signs of this anomaly are beginning to show on the continent.

In 2015, the Theewaterskloof dam, which supplies almost half of the water available to the city of Cape Town in South Africa experienced a series of droughts.

By 2018, Cape Town was approaching the days the taps ran dry nicknamed ‘DAY ZERO’, and people had to queue to get water rations.

Water crisis

Cape Town was not the first major city to risk running out of water. According to expert predictions, Jakarta, London, Beijing, and Tokyo could all face their own ‘day zero’ in the coming decades.

The water crisis extends throughout Africa, affecting millions of people and hindering socio-economic development. Only a third of Africa’s population has access to safe water, leaving millions to embark on arduous journeys daily to collect water from unsafe sources.

According to Nyika, J., Dinka, M.O. (2023) in a study initiated by the GIZ Sector Network, about 35% of the region’s population would have to embark on a 30-minute roundtrip to collect water: 13% would have to commute further distance to access clean water.

Despite these arduous journeys, about 15% of the continent’s population sources their water from unprotected wells and springs; and over 6% source their water directly from rivers, dams, and lake ponds.

Water supply in Ghana

The sources of water for Ghanaian households have predominantly been sachet water (37.4%), pipe-borne water (31.7%), and borehole/tube wells (17.7%) - ISSER (2023).

There is a significant gap in the rural-urban distribution of improved drinking water. Comparably, an estimated 2% of urban dwellers still do not have access to safe water whilst the proportion is estimated at 17% in rural areas.

Even though Ghana has made significant strides in improving its water and sanitation situation in recent years, access to water remains an existential threat to many Ghanaian households. Data shows that access to improved drinking water has increased by 10% from 2018 to 2021, with approximately nine out of 10 households having access (GSS, 2022).

Disparities

According to the Water Supply and Sanitation Joint Monitoring Program of UNICEF and WHO, there are also significant disparities in water access between urban and rural areas, as well as within urban areas. 88% of Ghana’s urban population (which constitutes 51% of the country’s total population) have access to at least basic water services, and 33% have household connections.

About 66% of rural Ghana (49% of the population): have access to at least basic water services, and 3% have household connections. Rural communities often rely on unimproved sources such as rivers, ponds, and wells, which are vulnerable to contamination and depletion.

Low-income urban communities face challenges such as intermittent supply, poor water pressure, high tariffs, and illegal connections. Non-revenue water loss stands at a staggering 50%. Treatment facilities are often undercapacity and require upgrades.

Ghana Water Company Limited (GWCL) operates 84 pipe-borne systems nationwide. There are 94 water treatment plants in operation, with a total installed capacity of about 949,000 cubic meters per day.

Achieving the objective of providing basic coverage for all by 2025, as outlined in Ghana’s Water Sector Strategic Development Plan, it will require a capital investment of US$ 327 million a year between now and 2025.

Recent studies show that while Ghana has come a long way in addressing infrastructure challenges, expanding the distribution network, and building climate resilience is crucial for ensuring equitable and sustainable water access for all Ghanaians.

By investing in technology, strengthening institutions, and embracing adaptable solutions, Ghana can guarantee its water sustainability in the foreseeable future.

Desalination

Desalination: A ray of hope

Desalination, the process of removing salt from seawater, holds significant promise in addressing water scarcity. It is a natural process that occurs when the sun heats the ocean and freshwater evaporates then falls back as rainwater.

With approximately 16,000 desalination plants globally producing around 100 million cubic meters of water daily, it is a proven method for securing a clean water supply.

Two primary desalination methods, Thermal desalination, and Reverse Osmosis, dominate the landscape, with the latter being more prevalent.

Thermal desalination is the oldest form of desalination which is essentially boiling water capturing the steam and turning that into freshwater.

Reverse Osmosis uses a tremendous amount of energy to pressurise the water through a semi-permeable membrane to force a separation between the salt and the water.

Despite the innovation processes of desalination, challenges persist, particularly in Africa. While the Middle East and North Africa account for a substantial share of desalinated water production, Sub-Saharan Africa lags, producing only 1.78 million cubic meters per day, a mere 1.9% of the global total.

This yawning gap raises questions about the feasibility of desalination as a widespread solution for Africa's water crisis.

The dilemma of desalination

Desalination, though effective, is not without drawbacks. Energy intensity, cost, and environmental concerns are some notable drawbacks. The amount of energy required for desalination, approximately 25 times that of other freshwater approaches, poses a significant challenge.

Moreover, the environmental impact, especially the production of hypersaline brine (highly concentrated salt solution), remains a major cause for concern.

Historically, the impediment to seawater desalination being popular worldwide and across Africa has been cost, exemplified by the Chtouka Ait Baha seawater desalination plant in Morocco which cost approximately US$478 million.

Investments

Such investments emphasise the financial commitment associated with desalination projects. Beyond the environmental cost of producing the energy needed to power these plants, another concern arises because the two broad types of the desalination process do not just produce clean desalinated water but also produce massive amounts of hyper-salty water called “brine” as a byproduct.

Seawater desalination plants that use reverse osmosis typically operate at 50% efficiency. That is if you take in two gallons of seawater, you are going to produce one gallon of freshwater and one gallon of hypersaline brine.

As desalination efforts grow, it is unclear what should be done with these massive amounts of brine. Globally we are producing 37 billion gallons of brine a day. Most brine is one way, or another emptied back into the ocean.

But because it has a much higher salt concentration than regular seawater, it has the potential to, among other things, sink to the seabed and wreak havoc on the living organisms beneath the sea. In addition, because these facilities are taking in millions of gallons of seawater a day, the intake itself could destroy local marine life.

Navigating the challenges: A portfolio

Approach Despite these challenges, desalination remains a stable and known process, providing a reliable source of clean water. Its advocates argue that while it may not be the sole solution to the global water crisis, it can be a crucial element in a diversified portfolio of water management strategies.

A notable example is Israel, which invested in desalination and water efficiency solutions. By reducing per-person water use, they delayed the need for large-scale desalination plants, showcasing the importance of a holistic approach to water management.

Desalination is a valuable tool in the fight against water scarcity, offering reliability in the face of climate change uncertainties. However, it is not foolproof, and other water management techniques must complement it.

Case of Ghana

In Ghana, one smart solution to our clean water problem is brackish water desalination. Brackish water is a type of water that is saltier than freshwater, but not as much as seawater typically found at the confluence of freshwater and saltwater, such as estuaries, lagoons, and coastal wetlands.

Unlike seawater desalination, which is energy-intensive, brackish water desalination works by turning slightly salty water into fresh water. This process demands far less energy and boasts a higher recovery ratio—up to 90% of fresh water can be produced from brackish sources.

For a country like Ghana, blessed with abundant water bodies but facing pollution challenges like galamsey, brackish water desalination offers a substantial solution. It is a more efficient way to combat water scarcity and ensure safe drinking water for communities in need.

With its potential to preserve clean water volumes and provide a sustainable solution, brackish water desalination deserves our attention and investment.

The contamination of water sources by heavy metals and other toxic substances due to the activities of small-scale miners is leading to a range of health problems, including neurological disorders, kidney diseases, cholera, bilharzia, asthma, and cirrhosis.

Wastewater generated in cities is saltier than freshwater but less salty than seawater. Therefore, a similar process used for seawater desalination can be used to treat wastewater generated in cities.

Based on the type and extent of contamination, numerous water treatment processes could be employed in turning wastewater into potable water. Some common water treatment methods include coagulation, flocculation, sedimentation, filtration, and disinfection. It is important to gain an understanding of the level of wastewater produced periodically by conducting studies in the field.

The last publicly available study which estimates that the total amount of wastewater (domestic- grey and black waters, produced in urban Ghana) to be approximately 280 million metric cubes was done in 2006.

Knowing the level of wastewater produced annually, the proportion which is treated, and finding the appropriate way of purifying the proportion which can be purified can complement new water sourcing efforts since the country faces dwindling water

sources due to activities such as “galamsey”.

The prospects of desalination in Ghana

Within the framework of Ghana's infrastructural challenges, desalination emerges as a distinctive opportunity. Private sector investments, technological advancements, and resource contributions can be pivotal in addressing the infrastructure deficit and establishing sustainable water solutions.

While desalination (both sea and brackish) alone may not resolve all water-related issues, its integration into a comprehensive water management approach holds substantial promise for alleviating the impact of water scarcity on the nation.

As traditional freshwater sources face depletion and Ghana encounters persistent challenges from climate change, the significance of desalination in shaping Ghana's water future cannot be overstated.

With technological progress driving down the energy requirements for seawater desalination, it is a promising solution for regions grappling with water scarcity.

In our pursuit of a sustainable future, the incorporation of desalination into a holistic water management strategy is imperative to ensure a consistent and accessible supply of clean water for all Ghanaians.

The writer is an analyst and sector specialist in charge of C-NERGY's Infrastructure and ICT desks.