Adieu, Doing Business - May your replacement be more robust

It is still hard to believe that Ghana’s political debates on the economy, call it ‘policonomics,’ will go on without the frequent reference to the country’s spot on the Doing Business (DB) index.

More shocking though is the revelation that the once influential World Bank index was prone to being gamed to hand countries attractive spots.

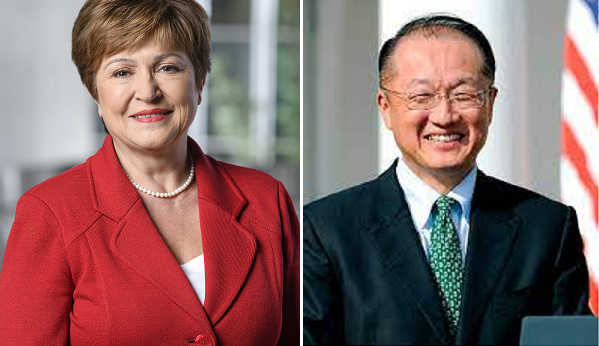

On September 16 when the index was being scrapped, evidence emerged of how two former senior executives pressured staff to give China and Saudi Arabia undeservingly good spots while ignoring significant changes in Azerbaijan that should have earned the Eurasian country a higher score.

As we mark the demise of the world’s one-time robust and best pointer to where private capital is most welcomed, it is okay to pause momentarily and ask: How many more years could the index have survived under these circumstances? And how deserving were the spots handed the countries in the 18 editions prior to its crumbling?’

The genesis

Founded in 2003 by the World Bank Group, the DB evolved into a report card for assessing how government policies aided or impeded business operations – right from starting a business to resolving one.

Its crux was that the fewer and more efficient the regulations, the better a country’s rank on the index. This, it believed, should raise the country’s potential to attract and retain investments, which should then lead to increased prosperity.

The index ranked countries on a scale of one to 190, with smaller numbers going for countries with more conducive environments for the private sector.

Impact

To a large extent, the index achieved its intended purpose quiet satisfactorily.

In the almost two decades prior to its demise, the annual publication grew into a powerful policy tool and trusted benchmark on how member countries improved or constrained their economies for private sector operators.

It also emerged into a primary advisory tool with which investors gauged where to deploy capital into.

For countries, it generally engendered positive rivalry and competition to gain brighter spots and attract investments. Ultimately, this led to a world of improved environments for businesses.

Ghana’s experience

Here in Ghana, various initiatives, the latest being the launch of the Business Regulation Reform programme in 2018, were undertaken to improve the business environment for the country to earn a better rank on the index.

The grand effort, with oversight from the Office of the Vice-President, came after the country had dropped significant points on the index.

It fell from the 108th position in 2016 to 120th in 2017, the worst in the country’s history, before improving to 118th in the last edition in 2020.

But it now appears that while Ghana and others implemented policies to be able to obtain favourable spots, the system was prone to being gamed and others worked to reap the benefit through ways that boosted their spots without recourse to the index’s requirements.

Skewed system

Even beyond the revelation in the World Bank-initiated investigation, experts had warned that developing countries were at a greater risk of losing out on the index.

In an opinion published in September 2020, urging the World Bank to scrap the DB index, a former Director of the International Labour Organisation (ILO) and UNICEF, Ms Isabel Ortiz, and a Director of the International Union Conference, Mr Leo Baunach, said the index “undermines social progress and promotes inequality”. They argued that it “encouraged countries to take part in the ‘deregulation experience,’ including reductions in employment protection, lower social security contributions (denominated as ‘labour tax’), and lesser corporate taxation.”

They are not wrong. Typical of such global initiatives, the index was based on general indicators, with less recourse to the peculiarities of developing countries such as Ghana.

First, it exemplified the perception that foreign direct investments (FDIs) are the cornerstone of development and that countries would have to give their all to attract them. This discourages local entrepreneurship as government efforts are largely channeled into creating the enabling environment to score higher marks and rake in more investments.

Here, the Ghana Union of Traders Association (GUTA) and the Association of Ghana Industries (AGI) have had cause to speak against such attitudes, although less attention has since been paid to them.

Tax as cost

Again, the index encouraged countries to cut corporate taxes, pay less in social security and ease regulations to allow private capital inflows.

These have the tendency to undermine government’s finances and impoverish retirees, given the cost tag placed on these two.

The peculiarity of developing country’s fiscal situations also means that lowering taxes to beat developed countries will turn in lower revenue to fund development. The result is high borrowing, which creates a macroeconomic challenge that the index did not measure.

Of critical importance is how data for the index was collected. In Ghana, poor road network and generally bad state of infrastructure means that businesses would have to bend backwards to thrive yet that was not featured.

There is also the general concern about the bank acting as a player and a referee. By setting out with a tool to measure what it terms necessary for businesses to thrive, many think the bank was conflicted.

Better model

In spite of its challenges, the index was relevant; at least for encouraging peer pressure among countries to improve the environment for businesses. Its absence creates a void.

Fortunately, the World Bank has hinted of plans to introduce a replacement. In its September 16 press statement announcing the scrapping of the index, the bank said it would “be working on a new approach to assessing the business and investment climate”.

While we await the details of that new approach, it is appropriate to say that the replacement must reflect the concerns that were repeatedly raised against the now defunct index.

Above all, it must not leave room for manipulations as that undermines the very foundation of even the bank’s existence – trust and integrity.