The role of trade in the work of the fund (1)

The Fund has a longstanding role in providing trade policy advice to its members through multilateral, regional, and bilateral surveillance.

The root of the IMF’s mandate primarily lies in Article I, which specifies that one purpose of the IMF is “to facilitate the expansion and balanced growth of international trade…”.

Trade work is carried out in three broad areas: (i) surveillance, where the bulk of the work takes place, (ii) lending, and(iii) capacity development.

While the underlying mandate has been constant throughout the Fund’s history, the level of attention and the type of issues addressed have evolved with changes in the global economy as well as staffing. As the 2009 Independent Evaluation Office (IEO) Evaluation highlighted, trade work peaked in the 1980s and 1990s.

Since then, a slowdown in the pace of trade reform, an increase in protectionism, and the risk of further reversals have been a drag on trade, productivity, and income growth.

Throughout the same period, the absolute number of IMF staff positions specifically focused on trade has declined by about three quarters (presently accounting for about 0.1 per cent of staff), prompting the IEO to underscore the need to maintain a “critical mass” of trade policy expertise.

This review follows the Board-endorsed recommendation by the IEO in 2009 to conduct periodic assessments of the Fund’s work on trade.

The last review took place in 2015, in which the Executive Board called for a work agenda to better embed trade in surveillance work, including translating key implications of the global trade landscape into surveillance (IMF, 2015).

The Board also called for tailoring coverage of trade issues in Fund surveillance to the specific needs of individual countries and ensuring that the Fund’s approach to trade policies was evenhanded.

At the same time, several Directors expressed reservations about a broader trade agenda that may have resource implications.

The 2019 IEO Update called for (i) better translation of multilateral surveillance into bilateral policy advice; (ii) deepened cooperation with other trade-related international organizations; and (iii) greater attention to rapidly developing issues such as digitization and e-commerce (IEO, 2019) (see Box 1).1

Implementation of these recommendations has been mixed. Amid declining overall coverage of trade policy issues and limited resources, the focus has been on responding to major global developments (e.g., the trade war) (see Chapter 3).

As a result, in most cases, there has been little attention to proactive policy advice tailored to a country’s own reform needs and bilateral trade policy surveillance has been focused on systemic countries.

Some forms of cooperation with the WTO have improved (in particular, joint policy analysis has demonstrated thought leadership and helped establish common views and perspectives), although there is further room to leverage

synergies with the WTO and other international organizations.

The 2019 IEO Update did not include recommendations for the Executive Board’s endorsement.

An overarching goal of this Review is to ensure that the Fund fulfils its mandate in this important area of work in line with changes in the world economy.

Beyond this broad goal, the current review has three specific objectives. First, to assess how the Fund’s work has promoted open, stable, and transparent trade. Second, to review and update policy advice on topical trade issues.

Third, to engage the Board on a future trade agenda for the Fund in light of the changing trade and trade policy landscape.

The review identifies three key trade-related challenges that the country authorities will face in the coming years.

• Climate change and technology. Structural forces such as climate change and technology are poised to reshape global trade by altering comparative advantage and making some previously non-tradeable services tradeable.

Resistance to shifting trade patterns could further erode support for open trade, underscoring the importance of domestic policies to adapt and to share the gains from trade and technological progress more widely.

• Using trade to accomplish non-trade objectives. This includes environment, inequality and inclusion, food security, public health, as well as national security concerns.

Closer links between trade and other policy areas have increased the need for policy coordination, as governments need to cooperate to keep trade open and carefully assess the impact of their measures on economic and non-economic outcomes at home and abroad.

• The intensification of geopolitical tensions. Geopolitical tensions increase the risk of geo-economic fragmentation, introducing uncertainty, reducing economic efficiency, and distorting investment patterns and decisions.

The WTO-based multilateral trading system was not designed to resist such pressures.

For instance, the WTO has active monitoring and transparency functions, but, in contrast to the IMF surveillance function, does not provide policy advice.

Mitigating risks from increased trade restrictiveness will require building awareness of the costs, voicing concerns, and promoting better policy choices.

A reinvigorated trade strategy should bring macroeconomic perspectives to the trade challenges identified above and bring a “Fund” perspective to key global trade policy debates—including in the WTO.

The strategy should bring macroeconomic perspectives in a way that is selective and effective to best meet the Fund’s broad mandate on trade.

While much of the work will remain decentralized across Fund departments, this more active engagement will require to scale up the internal trade policy expertise to support surveillance and other activities.

Fund work on trade should continue to be carried out through three main channels:

• Analysis and multilateral surveillance should boost efforts to identify major trade-related developments and risks and provide the intellectual leadership and analytical underpinnings for Fund policy positions.

income developing countries (LIDCs) and reducing barriers to services trade.

• For emerging markets, priorities include further liberalization of goods and services markets, including for products of export interest to LIDCs, and better-integrating trade policy into the structural reform agenda.

• Low-income countries should complement openness with improved trade infrastructure, better economic institutions, and increased access to regional and global markets, including through the implementation of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement.

The remainder of the report expands on these themes and is organized as follows.

Changing trade landscape

Global trade is not in retreat, but it is changing and facing mounting risks. In recent years, the growth of goods trade has decelerated, while services trade has shown more dynamism; EMs have been playing a larger role in world trade, including trading more with each other; and shocks such as the pandemic have put world trade under stress, although global value chains have so far shown resilience.

In the past three decades, the growth of goods trade has decelerated, while services trade continued to expand more rapidly (Figures 1 and 2). Since 2011, the growth rate of goods trade has slowed to an annual average of 4.1 per cent (down from an annual average of 9.1 per cent during 1990 to 2008).

Global goods trade also reduced as a share of global GDP, from 51.0 per cent in 2008 to 46.5 in 2021. Meanwhile, the world economy experienced robust growth in services trade from $1.6 trillion in 1990 to $11.5 trillion in 2021, an average annual growth rate of 6.9 per cent.

Trade costs in services have traditionally been much higher than those in goods but due to the advances in digital technologies, they are dropping at a faster rate—a trend that is likely to continue

The persistent slowdown in goods trade started before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) mostly due to structural factors. The rise of

GVCs promoted by technological innovation and trade liberalization enabled the rapid growth of goods trade starting in the late 1980s.

The increasing fragmentation of production stages across multiple countries allowed many emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) to expand their participation in international trade.

However, this expansion slowed over time as the impact of technological innovation and trade reforms waned.

Constantinescu, Mattoo, and Ruta (2020) found that this slower expansion in GVCs, especially as China's growing production of intermediate goods replaced imported inputs, is a main driver of the long-term decline in the growth of goods trade.

Other factors, such as the weakness in economic activity after the GFC, particularly in investment, and the waning pace of trade liberalization and the persistent increase in trade protectionism have contributed to holding back world trade growth (IMF, October 2016, WEO Chapter 2).

The contribution of EMs to global trade has grown notably in the past three decades, albeit at a slower pace since 2011.

AEs accounted for 82 per cent of global goods trade in 1991. Since then, EMDEs have robustly improved their share of global merchandise trade, driven by the integration of China and other EMs in the world economy.

AEs account for more than 75 per cent of services trade, a share that has been fairly stable over the period (Figure 5). EMs have increased their share in services trade to 24 per cent, although this growth was mostly concentrated in China and India.

The low participation of other EMs and LICs points to more limited investment and higher barriers to services trade.

There has been a significant shift in the pattern of international trade flows from and towards EMDEs. In the past three decades, the share of trade among EMDEs has increased by more than fivefold, from 3.4 per cent in 1990 to 18.7 per cent in 2021 as more EMDEs participated in global value chains.

The share of exports of AEs to EMDEs has been relatively stable while the share of trade among AEs in global exports has declined from 68.8 per cent to 37.1 per cent.

For LICs, the major improvement has been in the share of their exports to EMs (from 0.3 per cent to 2.7 per cent of global exports) partly due to rising commodity demand in EMs and their growing domestic markets.

Goods trade in some regions is more integrated than others, but in the last decade, the shares of trade among regions have been stable across the globe. The share of goods trade within Europe and East Asia and the Pacific is substantially higher compared with the other regions of the world.

This higher share in part reflects the importance of regional value chains and trade reforms at the national (East Asia) and regional (Europe) level. In the past decade, the shares of regional trade have been largely stable in most areas.

Deeper forms of regional trade agreements, such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), can be important in promoting intra-regional trade in regions that currently display low levels of integration and support further integration into the global economy.

The pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine have disrupted international trade, although their long-term implications are still unfolding.

World trade sharply declined at the outset of the pandemic, but goods trade recovered quickly.

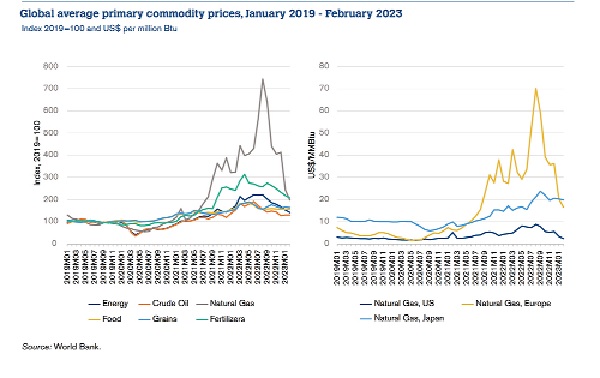

The war in Ukraine primarily impacted trade in food and energy products (Russia and Ukraine together account for a quarter of global exports of wheat and natural gas) and had broader short-term effects through multiple channels, including logistics, especially shipping, disruptions and sanctions that were imposed on Russia and Belarus (Ruta, 2022).

In the longer term, these events have contributed to reducing the trust in the open trade system and have exacerbated geopolitical tensions which are in part responsible for the surge in trade distortive measures discussed in the next section.

While structural factors have played a major role in explaining long-term trends in world trade, as discussed above, the increase in trade policy activism could become a more significant headwind for trade integration.

Factors unique to the pandemic contributed to the sharp decline and faster-than-usual rebound in goods trade.

Lockdown policies were a key driver of the trade collapse early in the pandemic; these spillovers were mitigated in industries where telework was a possibility and has diminished over time as firms adapt to the public health measures.

Fiscal and monetary stimulus, the simultaneous rotation of consumer demand away from services into durable goods in AEs, and the increase in demand for imported pandemic-related medical goods contributed to the strong rebound in goods trade, surpassing pre-pandemic levels in 2021. Global shipping costs spiked during the pandemic and further impacted trade flows.

Shipping costs soared as consumption shifted away from services to durable goods and lockdowns, labour shortages, and strains on logistics networks mounted.

These effects further disrupted the world’s supply chains (Carriere-Swallow and others, 2022; Celasun and others, 2022; Komaromi, Cerdeiro, and Liu, 2022).

Global container rates surged throughout 2021, but it also shows that these rates declined afterwards, and eventually returned to pre-pandemic levels, as consumer spending on services recovered and pressure

on global supply chains eased.

A key policy lesson from the pandemic is the need to improve diversification through open trade as a means to enhance GVC’s resilience.

Future shocks can have very different geographic origins and contagion dynamics, but some policy lessons from the pandemic is generalizable.