Aren’t our palanquin carriers tired?

The chieftaincy institution in Ghana must be commended for ridding itself of antiquated practices.

Gone happily is the practice of cutting human heads with the belief that the victims would accompany the dead chief as a servant in the netherworld.

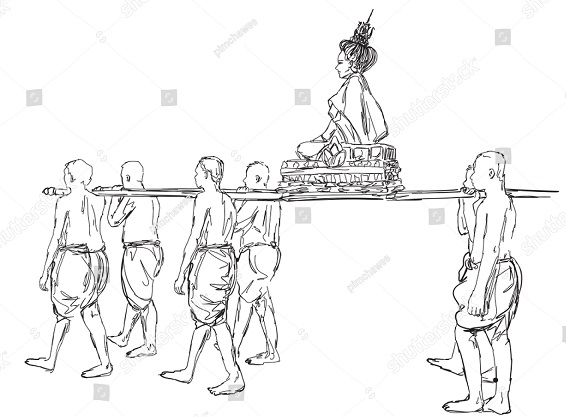

There is one practice, however, that is refusing to go away - the carrying of chiefs on human heads and shoulders.

It is not going away because the public seldom, if ever, complain. They don’t complain because everybody is filled with a sense of pride on seeing their chiefs so high and lifted up.

Truth, however, be told: it is a national shame. It places us on the undesirable side of antiquity.

Worse, it is an injury to the humanity of the carriers, all in the belief that it is Ghanaian culture.

Unknown to many of our chiefs, palanquins are not necessarily “typical Ghanaian or African culture”.

The practice has attained the “culture” nomenclature only because it has carried on for well over a century.

Like cloth wearing, carrying people around in palanquins did not originate in Africa, and those who began it have abandoned the practice because it is economically unprofitable, socially backward and a human right abuse.

Earliest reference

The earliest reference of the use of palanquin, is traced back to Ramayana, India, approximately 250 years before Jesus Christ was born (250 BC).

Portuguese and Spanish navigators and colonisers who saw palanquins in India, Mexico, and Peru, exported the concept to Spain, France and Britain.

In ancient times, it was a luxury on the part of the pre-modern aristocratic and affluent people to move in palanquins.

During the 17th to 18th centuries, palanquins were very popular among European traders in Bengal, so much so that in 1758 an order was issued prohibiting their purchase by certain lower-ranking employees.

In Europe, this mode of transportation met with instant success. Henry VIII of England (1509-1547) was carried around in a sedan chair—it took four strong “chair-men” to carry him towards the end of his life.

In various colonies, palanquins were often adopted by the white colonials as a new ruling and/or socio-economic elite.

The practice began to decline from the mid-19th century. With the development of roads and highways, the palanquin as a means of transport faced extinction: by the 1930s it had been ousted from urban areas.

By 1960s, nobody used palanquin to assert his/her importance in society. It was an anachronism.

In Africa, palanquins were in use in the Kingdom of Kongo as a mode of transportation for the elites as far back as the 15th century.

Even in this part of Africa, it was abandoned with time as economic improvements opened the eyes of humans.

Reasonable

It is reasonable to suspect that the reasons for accepting the use of palanquins wherever they were introduced may have been the same for people of this land mass that existed before Gold Coast, now Ghana.

Palanquins set the chiefs apart. They looked great. Even a (wo)man with failing sight would not fail to appreciate the sight of a winding parade of a dozen or more paramount chiefs on the way to a state durbar ground.

So beautiful your heart will miss several, if not many, beats.

Be that as it may, palanquins are an unacceptable relic. It dehumanises the carriers, consigning them into slavery forever.

It has been argued that unlike palanquins for commercial use, Ghanaian chiefs are carried around over very short distances.

I disagree. Long or short, it is dehumanising to the carriers. The last time I checked, Ghana had long joined the rest of the world into the 21st Century. Some of our chiefs hold PhDs and professional degrees, etc.

If the practice has to stop, it will not be for lack of carriers; indeed, as in ancient days when royal brides in India were carried in ornate palanquins, even the men who carried them, that is, the palanquin bearers, considered it a privilege to carry the bride.

Remember the plight of the Kru men in Ghana from Liberia in the mid-to-late 20th century?

Theirs was a sorry sight to behold as they carried on their heads, through the streets of Ghana, human excreta gathered from pan latrines from house to house for disposal into the sea.

For survival, they did ask: must human beings, even if they are cursed, be sentenced to life with dancing chiefs on their heads or shoulders?

Two or so years ago, a chief in Central Region of Ghana refused to be so carried. He was transported from the palace to the durbar ground in an open car.

Nobody has copied his shining example, unfortunately.

The writer is the Executive Director, Centre for Communication and Culture, E-mail: