Welcome has generated the biggest debate in Ghana this week, no cap!

Despite being a Dangme and having been born and lived in Accra all my life, I only know Mohee as a welcome greeting in my language.

Moving further into the GaDangme group, I was not sure I knew a specific word for welcome apart from Naa lɛ ee or Bo kɛ hiɛmɔ dzrɔɔ — or some other combination of words used to warmly welcome someone or a group.

It is amazing, if not slightly embarrassing, to say that this is the first time I am hearing that the Ga word for welcome is Oobakɛ (to one person) or Nyeebakɛɛ (to a group). Very intriguing indeed.

This, perhaps, is one of the few positives about the current debate: it has opened up an avenue for many of us to learn more about the greetings of Ghanaian ethnic groups and their linguistic traditions.

Yet the controversy about replacing Akwaaba with Oobakɛɛ at the Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Park raises deeper questions about tourism, identity, nation branding and unity.

Why the agitation?

The agitation began because the signage at the refurbished Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Park once displayed both Akwaaba (Akan) and Woezor (Ewe).

Some Ga voices argued that since the park sits on Ga land, the greeting there should reflect the Ga language — in this case, Oobakɛ.

The same reasoning has been extended to Kotoka International Airport, which is also located in Accra, on Ga land.

At face value, this argument may appear straightforward.

Every community wants its culture and language to be visible, especially on facilities within its geographic space.

However, this debate overlooks a critical fact — these facilities are not simply local.

They are national monuments and gateways that serve the whole of Ghana and represent the entire country to the world.

Beyond local identity

Here is where clarity is needed. The Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Park is not just a tourist attraction in Accra.

It is a national “shrine” dedicated to Ghana’s first President, a global figure, and a unifier.

Similarly, Kotoka International Airport is not merely an airport on Ga land. It is Ghana’s foremost international gateway, welcoming millions of visitors from across the globe.

These facilities are national symbols, and their messaging must be framed with the national and international audience in mind.

The Ghana Tourism Authority (GTA), though responsible for marketing Brand Ghana, does not own or control these facilities.

But because they are the points of first contact for most visitors, the greetings and signage used there must align with the national tourism brand.

That brand is built on the global recognition of one word - Akwaaba.

This is why Akwaaba has been so effective.

It has grown beyond its Akan origins into a word that belongs to all Ghanaians. It is simple, recognisable and has become globally associated with Ghana’s identity.

Anywhere in the world, when people meet Ghanaians, the first word they greet you with is Akwaaba.

To complicate this with competing ethnic claims at national monuments is to weaken our strongest tourism brand.

How Akwaaba became iconic

The prominence of Akwaaba in Ghana’s tourism story owes much to the creativity of Joe Osae, founder of Ceejay Multimedia.

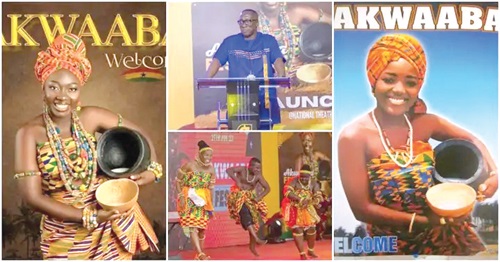

In 1999, he produced the now iconic image of a smiling young Ghanaian woman draped in Kente cloth, holding a pot and calabash, and simply branded it “Akwaaba - Welcome.”

That image travelled far and wide, appearing in airports, embassies, hotels and cultural spaces, and came to symbolise Ghanaian hospitality.

It even gave birth to the celebrated Akwaaba Festival, cementing the word’s place in our cultural imagination.

It is against this backdrop that the recent change of signage at the Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Park — from Akwaaba and Woezor to Oobakɛɛ — feels unsettling. Something that has grown organically into a unifying national brand is now at the centre of agitation and contestation.

The bigger question emerges: Do we risk weakening our national brand by giving in to ethnolinguistic claims, or do we protect the identity that has already served us well on the global stage? That’s the conundrum!

Lessons from other countries

Other African countries with multiple languages have faced similar issues but chosen a pragmatic path.

In Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda, despite having dozens of ethnic groups, the Swahili greeting Karibu has become the standard word of welcome in tourism and branding.

In South Africa, with its 11 official languages, it is the Zulu greeting Sawubona that is most often projected in cultural export and imagery — even the in-flight magazine of South African Airways is titled Sawubona.

The lesson is clear: for nation branding, you need simplicity and consistency. Local languages can and should be celebrated in their own spaces, but at the national and international level, one greeting must carry the weight of identity.

Ethnocentrism and unity

The conversations thus far about Oobakɛ replacing Akwaaba at these national facilities have come across as ethnocentric, even if that was not the intention.

Whether subtle or overt, this kind of agitation fractures rather than unifies.

Visitors are not here to parse our ethnic rivalries. They want a clear, warm and recognisable welcome. Akwaaba provides exactly that.

The irony is that this controversy is playing out at the Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Park — the final resting place of the man who worked so hard to unite Ghanaians and Africans beyond ethnic and tribal lines.

To have his memorial become a flashpoint for ethnolinguistic competition is both unfortunate and misplaced.

Way forward

The way forward is simple:

• Retain Akwaaba as Ghana’s national welcome word for tourism and branding.

It is tested, trusted and globally recognised.

• Celebrate Oobakɛ, Woezor, Mohee and others in cultural festivals, local events, community signage and educational programmes.

These enrich our cultural tapestry without diluting our national identity.

• Use this debate as an education. Many of us, myself included, have only just discovered Oobakɛ through this conversation. That awareness is valuable — but it must not come at the expense of what already works for Ghana.

Conclusion

Nation branding requires clarity and focus. Ghana has something powerful and universally recognised in Akwaaba.

Let us protect it and project it, while respecting and celebrating the diversity of our languages in their rightful spaces.

Akwaaba is no longer just Akan. It is Ghanaian. It is African. And it should remain the word with which we welcome the world.