The coastal belt of Ghana stretches from Volta through Greater Accra, Central and ends at the Western Region.

The coastal belt embodies unique habitats that harbour diverse plants, many of which have medicinal uses; therefore, they have become part of the ethnobotanical heritage of the people living in communities dotted along the coastal belt.

The brackish (lagoons and estuaries) water mangrove ecosystems are home to many medicinal plants, including Rhizophora racemosa, Avicennia africana and Jatropha curcas.

In view of the harsh and highly unstable nature of these coastal habitats, plants that do thrive in such harsh and unpredictable environments have developed diverse survival strategies (adaptations) in the course of their evolution.

Common among these adaptations are their ability to withstand salinity, water stress, nutrient stress, the tricky sandy beaches, the winds and the temperature fluctuations.

The adaptations mainly take two forms, morphological (physical) and chemical (production of secondary plant metabolites), with the chemical adaptations being dominant.

Therefore, plants that thrive in such highly unstable and harsh habitats, such as the mangrove swamps, are enriched with diverse secondary plant metabolites (natural products), most of which account for their ethnobotanical uses by the local communities.

Sad to say that most of these ethnobotanical uses remain undocumented.

The secondary plant metabolites and their functional group enrichments confer biological properties (e.g., anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-hypertensive, anti-microbial, anti-tussive, anti-cancer, anti-malaria, anti-diarrhoea properties) on these medicinal plants (parts used in ethnomedicine) that are relevant for therapeutic exploration, yet remain untapped.

Diseases such as skin infections, upper respiratory disorders and gastrointestinal diseases are mostly treated by local people in the coastal communities, relying heavily on medicinal plants as the first line of treatment.

For example, Terminalia catappa, commonly called ‘almond’, is revered by local communities dotted along the coastal belt for the ability of its bark preparation to treat sore throat and diarrhoea.

Similarly, Calotropis procera, commonly called ‘Sodom apple’ and common along the coastal belt, is traditionally used to treat fever, skin infections and rheumatism.

Crucial

It goes without question that the crucial standing of ethnobotanical heritage dominated by medicinal plants in the lives of people living in coastal communities.

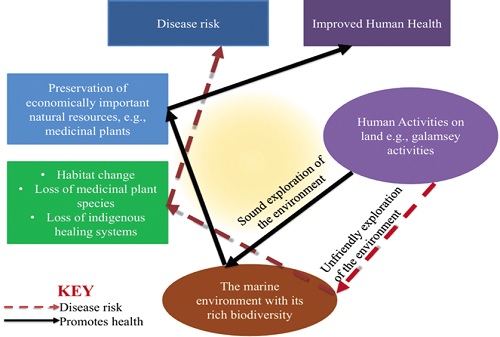

However, this crucial role of ethnobotanical heritage of the people dominated by medicinal plants is threatened by many emerging exigencies, including medicinal plant species loss due to galamsey-related activities (chemically contaminated surface waters and flood waters that enter estuaries and lagoons en route to the sea), habitat loss/change (environmentally unfriendly human activities along the coast belt, e.g., defecation into the sea, sand winning, washing of clothes in the sea, deposition of refuse into the sea, poison fishing in the sea, etc.) and most importantly loss of ethnobotanical knowledge (loss of key custodians of indigenous knowledge and the attendant break in the transmission of indigenous knowledge from one generation to the other through oral traditions).

It is largely held that over-reliance on oral tradition (as pertains in coastal communities) alone as a means of preserving indigenous knowledge is much to blame for the loss of indigenous knowledge.

Certainly, the negative impact of these factors, particularly ‘galamsey’ activities and their contribution to loss of medicinal plants in the coastal belt of Ghana, though it may seem remote, needs holistic and urgent attention.

It is apparent that ‘galamsey’ activities, though far from Ghana’s coastal areas, may still affect species diversity of medicinal plants along the coastal belt, given that surface waters of all kinds first influence the vegetation cover of the beaches before entering the sea.

Impact assessment of surface waters largely carrying toxicants and other contaminants from land-related activities such as ‘galamsey’ needs not only to be addressed from the environmental standpoint but also tailored to include impact assessment on the diversity of medicinal plant species along the coastal belt.

Documentation of medicinal plants along the coastal belt of Ghana by relying on surviving custodians of indigenous knowledge, as well as use of field studies to identify threatened and endangered medicinal plant species are crucial, since such a data will inform the basis for novel strategies to mitigate the negative impact of ‘galamsey’ on biodiversity of medicinal plants along Ghana’s coastal belt.

Finally, any novel strategy to salvage the negative impact of ‘galamsey’ on medicinal species biodiversity along the coastal belt should have a trans-disciplinary outlook that will draw on the expertise of marine ecologists, environmental scientists, pharmacognosists, plant breeders, pharmacologists and natural product scientists.

The writer is with the Department of Medical Laboratory Science, School of Allied Health Sciences, College of Health and Allied Sciences, University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast.

E-mail: aboye@ucc.edu.gh