Growth in sub-Saharan Africa to rebound next year

2023 has been a difficult year for activity in sub-Saharan African economies. The inflationary shock following Russia’s war in Ukraine has prompted higher interest rates worldwide, which has meant slowing international demand, elevated spreads and ongoing exchange rate pressures.

As a result, growth in 2023 is expected to fall for the second year in a row to 3.3 per cent from four per cent last year.

The region is expected to rebound next year, with growth increasing to four per cent in 2024, picking up in four-fifths of the sub-Saharan Africa’s countries and with strong performances in non-resource intensive countries.

Macroeconomic imbalances are also improving—inflation is falling for most of the region and public finances are gradually being put on a more sustainable footing.

But the rebound is not guaranteed. A slowdown in reform efforts, a rise in political instability within the region, or external downside risks (including from China slowing down) could undermine growth. Moreover, four clouds are on the horizon which require determined policy action in the face of difficult tradeoffs:

First, inflation is still too high. It is in double digits in 14 countries. And it remains above target in most countries with explicit targets.

Second, the region continues to face significant exchange rate pressures.

Third, debt vulnerabilities are elevated. The funding squeeze is not over, as borrowing rates are still high, and rolling over debt is a challenge. And half of the low-income countries in the region are at high risk or in debt distress.

Finally, while the recovery is underway, economic divergences within the region are widening—in particular, per capita incomes in resource intensive economies remain subdued.

Against this background, the policy priorities are as follows:

• Addressing inflation;

For countries where inflation is high but falling, a “pause” may be warranted, with rates held at existing elevated levels until inflation is firmly on the path to target.

In countries with still rising inflation, further monetary tightening may be required until there are clear signs that inflation is cooling.

• Managing exchange rate pressures:

For pegged countries, monetary policy needs to be aligned with the anchor country to preserve external stability and prevent further losses of reserves.

In countries with floating exchange rates, currencies should be allowed to adjust as much as possible since efforts to resist fundamentals-based movements come at a significant cost.

The adjustment should be accompanied by other policy measures—tighter monetary policy to keep inflation in check, targeted support for the poor, structural reforms to strengthen the export sector, and fiscal consolidation where the fiscal deficit is adding to exchange rate pressures.

• Managing debt obligations while creating space for development spending:

For much of the region, fiscal policy must adapt to a tighter financing envelope and elevated debt vulnerabilities. This involves better mobilising domestic revenue, a strategic approach to spending, borrowing prudently, and anchoring fiscal policy through a credible medium-term framework.

In the few countries where debt is unsustainable, debt restructuring may also be needed. With large development needs and limited fiscal space, most countries need greater financial support from donors.

• Improving living standards and potential growth, particularly in resource intensive countries:

Boosting income per capita will require wide-ranging structural reforms, including investment in education, better natural resource management, improved business climate and digitalisation and a commitment to trade integration.

Region to rebound in 2024

Model estimates suggest the region’s recovery may already have started. GDP data for most countries are still only available for Q1 2023. But high frequency indicators show that aggregate activity for the region improved in the second quarter 1.

Important for the region, disruptive power shortages in South Africa picked up significantly in 2022 and have weighed on that country’s growth in 2023—but even here outturns for the first half of the year have been better than anticipated, owing to the lower-than-projected impact of power shortages and the ongoing strength of the services sector.

Looking ahead, the relative size of South Africa (19½ per cent of regional GDP) means that average regional growth in 2024 will largely reflect South Africa’s coming recovery (Figure 2), which in turn will be driven by that country’s efforts to address pressing issues in the power sector.

But the region’s recovery extends beyond South Africa. Indeed, in stark contrast to 2023, growth will improve in around four-fifths of the region’s economies.

Divergence

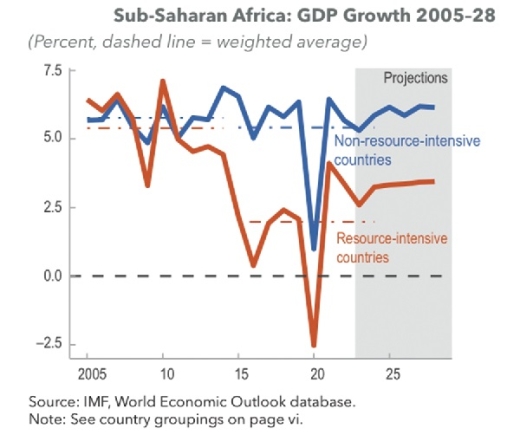

Still, there is significant heterogeneity across the region—in particular, the divergence between resource-intensive and non-resource-intensive countries is expected to persist.

Both groups of economies will recover next year but at different paces. Subdued commodity prices will continue to weigh on exports for most resource-intensive economies, but overall growth will improve nonetheless from 2.6 per cent in 2023 to 3.2 per cent in 2024, buoyed mainly by private consumption and in some cases, a number of new (or repaired) hydrocarbon projects coming on stream (Niger, Senegal) and mining projects starting production (Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia, Mali, Sierra Leone).

Growth in non-resource intensive countries on the other hand will be supported by both consumption and investment and is expected to improve from 5.3 per cent to an impressive 5.9 per cent.

This two-speed recovery is a long-standing pattern, becoming particularly pronounced following the commodity price shock of 2015 (see “Recovery Amid Elevated Uncertainty,” Chapter 1 in Regional Economic Outlook: Sub-Saharan Africa, April 2019).

Since that episode, the divergence between these two types of economies has become more entrenched. Neither group of countries is expected to completely recover lost ground from the crisis, but non-resource countries have nonetheless proven more resilient, supported by their more diversified economies.

For resource-intensive economies, on the other hand, a less diversified structure along with greater exposure to external shocks has weighed on investor confidence and activity—weakening prospects in the short term and undermining potential growth in the long run.

External conditions improving

Although the global environment remains difficult, some improvements have been observed since the April 2023, Regional Economic Outlook: Sub-Saharan Africa:

First, after three long years, the World Health Organisation has declared that the pandemic is over.

Second, consumption has proven unexpectedly resilient across numerous large economies, so that (still downbeat) projections for global growth in 2023 have been revised upwards since April.

Third, global inflation is slowly falling. Policy-rate hikes in many large economies are now on pause and international financial conditions are easing—which has helped reduce sovereign spreads for sub-Saharan African countries, taking some pressure off the funding squeeze.

Finally, global supply chains have normalised and food and energy prices have fallen. International food prices have dropped by over 20 per cent over the past 18 months.

With food being close to 40 per cent of sub-Saharan Africa’s consumption basket, this is good news for a region grappling with an acute cost-of-living crisis and an already-troubling incidence of poverty—about a third of the population in sub-Saharan Africa is estimated to live under $2.15 a day.