A date with Opoku Ware School ‘ancestors’

It is not very often that one gets to fraternise with one’s ancestors. Indeed, the whole idea of ancestors is that they belong to yesteryear and are quite far removed from the grime of daily life, spiritualised and immortalised, in many cases sanitised as distant, quasi-mythical figures of legend that inspire nothing but awe in future generations.

A short, long ride

I was thus excited when the opportunity presented itself for us old boys of Opoku Ware School to meet the pioneering class of students that started the school on 28th February 1952. On that day, 60 young boys began a journey from St. Peter’s Cathedral in Kumasi to a small clearing in the bush somewhere on the outskirts of the city on the Obuasi road. It was a short ride for them that day, but it has been one long, thrilling ride over the years.

They were the newly-minted class that was to start a Catholic secondary school for boys. They were driven to school by their new headmaster, Father P. R Burgess, an Irishman born and bred in England. Subsequently others joined them and the number swelled to 71. They were known as the K batch, and began the numbering system that the school is so well known for and which irritates our arch rivals down the road in Sofoline. Sadly, only 7 of the 71 boys remain alive.

The date

Our date with our surviving ancestor pioneers on Sunday, the eve of the 70th anniversary of that momentous journey, was in three parts. At the St. Theresa’s Parish Church in Accra, a thanksgiving Mass was held with two of the pioneers (K27 and K45) in attendance. I dashed from an out-of-town work retreat to be there on time.

In Kumasi, K36 graced a special occasion at the school whilst a delegation of old boys travelled to Berekum to spend some quality time with K38. K2 lives in Germany, and two others, K15 and K36 were unable, sadly, to make it to any of these events.

To have a conversation with these men was nothing short of magical and one could feel a keen sense of a connection with the past that enabled one to appreciate some history even better and situate it in context.

It was like being in the presence of an aged veteran who had fought in a war that took place when you were not born, or being regaled with story by a wily grandmother about her experiences as a little girl of a great distant earthquake or even of when independence came.

These experiences give you more than you could ever read in dry history textbooks written by people who were not even around when the said events took place. Luckily, back in 2015 the alumni group commissioned a book on the history of the school and their perspectives about the early years proved most invaluable.

Quality time

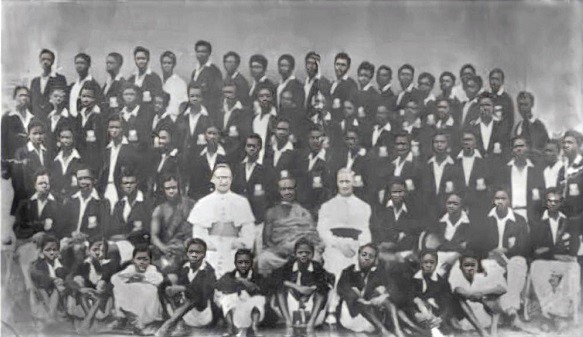

As we broke bread, cut a cake, popped champagne, made merry and spent absolute quality time with our seniors, their frailty and slow gait did not escape any of us. Looking at their official inaugural class photograph in with the Asantehene, the Bishop of Kumasi and their headmaster, it was almost impossible to accept that many of those nimble, agile testosterone-laden boys staring intently into the camera are no more, and that those that survived are rather frail.

Every day these octogenarian ancestors remain with us is a precious one for which we are immensely grateful, and we have to come to terms with the reality of the obvious inevitability at some point, hopefully very far away. The group photographs we took with them will be forever cherished.

Rat race

As I travelled home flushed with excitement that I had shaken hands and chatted with two ancestors of my school, together with their obvious excitement that we had found time to appreciate them and spend some time with them, I could not help but wonder the value we as a society place on our aged. Is it not the case that primarily, in the rat race of modern life to keep body and soul and family together, we have, perhaps unintentionally, literally shunted our elderly folks to the sidings and left them in their own little corner, frail and moping?

Our close-knit extended family system, which had the elderly as a core part who babysat their grandchildren whilst their parents went out to farm or to trade and provided a certain family gravitas, is gradually breaking apart and being atomised in the name of modernity and ‘civilisation’.

No relics

Our elderly are not ancient relics to be kept in a dank, dusty basement and almost forgotten about. They are an important part of the fabric of our society – the crucial bridge, if you like between our past and our present. Many of them, especially those who blazed important trails in their heyday, set records, broke ceilings and caused a buzz, have so much to share, but we seem to always be on a buzz as a society and have little time to stop and catch our breaths. With the joys of technology at our service to freeze people in time, we must as a nation take more interest in recording for posterity.

Of course, I am no ancestor – indeed I am a spring chicken in relative terms- but many young people go wide-eyed when I tell them about the reality of curfews, food crisis and other such realities of life in this country during the revolution in the 1980s.

If we found time to chat, to rediscover our past through the lenses of our senior citizens in our families and beyond and enjoy their perspectives before the final curtain call, there is so much we could learn from them to enrich our individual lives and our society.

This year promises to be exciting with a number of activities to mark Opoku Ware School’s 70th birthday, culminating in a grand durbar in Kumasi on 3rd December 2022. We hope to see all our surviving pioneer ancestors there, and beyond that, we hope to see them when we hit our 80th birthday in a decade.

Rodney Nkrumah-Boateng (rodboat@yahoo.com)