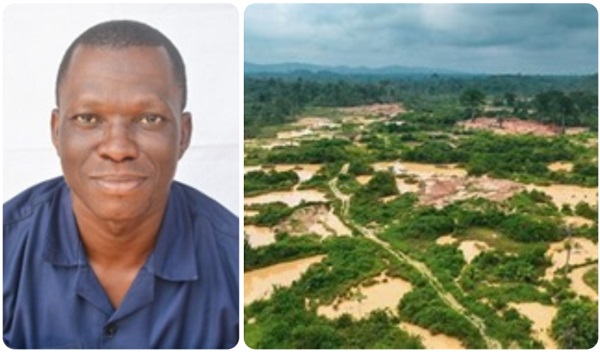

Galamsey, Ghana’s illegal small-scale mining epidemic, has evolved from rudimentary pick-and-shovel operations into a highly sophisticated, militarized industry that threatens national security, environmental sustainability, and human lives.

Once artisanal miners driven by poverty, today’s galamsey networks operate as organized criminal syndicates armed with advanced weaponry, cutting-edge technology, and vast financial resources. These groups now deploy AK-47 rifles, drones for surveillance, excavators, and mercury-laden industrial equipment to plunder Ghana’s gold-rich lands (Ghana Police Service, 2023).

Their operations are no longer clandestine; they brazenly occupy forests, farmlands, and riverbanks, guarded by armed enforcers who shoot at will to protect their illicit gains (Amnesty International, 2022).

Recent intelligence reports reveal that galamseyers have formed alliances with transnational crime networks, enabling them to procure military-grade weapons and encrypted communication systems.

For instance, in 2022 alone, security forces confiscated over about 1,500 illegal firearms, including submachine guns and grenades from galamsey sites in the Ashanti and Western Regions.

Satellite imagery further exposes the scale of their fortified camps, complete with trenches, watchtowers, and armed patrols along decimated riverbanks. This militarization has turned galamsey into a lethal enterprise: between 2020 and 2023, over 50 security personnel and 120 civilians were killed in clashes with these armed groups, while hundreds more suffered injuries (Human Rights Watch, 2023).

The environmental toll is apocalyptic. Forests that once spanned 8.2 million hectares now stand reduced to 5.8 million, with galamsey responsible for nearly 60% of this loss. Toxic chemicals like cyanide have turned critical water bodies such as the Ankobra and Offin Rivers into lifeless, orange-hazard zones, depriving about 4 million Ghanaians of safe drinking water. Farmlands lie scorched and barren, displacing rural communities and exacerbating food insecurity in regions like Amansie West, where cassava yields plummeted by 40 per cent in 2022.

Despite legislative frameworks like the Minerals and Mining Act (2006) and military-led initiatives such as Operation Vanguard and the recent ‘Surgical’, the state’s response has been catastrophically outmatched. Galamseyers exploit legal loopholes, corrupt officials, and their firepower to evade arrests, rendering traditional law enforcement futile.

In this context, the proposed “Shoot to Kill” policy emerges not as an overreach but as a constitutional imperative. Under Article 13 and 41(k) of Ghana’s 1992 Constitution, the state is obligated to protect the environment “for posterity,” while Section 2(1b)of the Public Order Act (1994) suggests the permission of lethal force to neutralize threats to public safety. When miners arm themselves to wage war against the state, the line between criminality and terrorism blurs, and extraordinary measures become unavoidable.

This paper contends that Ghana’s survival hinges on dismantling galamsey’s militarized infrastructure through calibrated, lawful force. By presenting geospatial evidence of environmental carnage, forensic data on weapon proliferation, and legal precedents for lethal engagement, this analysis justifies “Shot to Kill” as a last-resort policy to reclaim Ghana’s future.

The Destruction Wrought by Galamsey

Environmental catastrophe

Galamsey has metastasized into an environmental apocalypse, annihilating ecosystems that sustain Ghana’s biodiversity and livelihoods. Satellite imagery from NASA’s Earth Observatory (2023) reveals that illegal mining has degraded 40% of Ghana’s forest reserves since 2015, with the Atewa Range Forest, a UNESCO-designated biodiversity hotspot, losing 25% of its canopy since 2020.

The use of excavators and mercury has turned once-fertile farmlands into toxic wastelands. In Amansie Central District, about 80% of cocoa farms have been rendered barren, costing farmers $120 million annually.

Water bodies are equally devastated. The Pra River, which supports nearly 5 million people, now has turbidity levels 30x above WHO standards due to siltation from galamsey. (Figure 6). Fish populations in Lake Bosomtwe have declined by 70%, threatening food security (Water Resources Commission, 2023).

Human Toll

Galamsey’s socio-economic impact is equally dire. A 2023 study by the Ghana Health Service linked 65% of pediatric hospitalizations in mining regions to mercury poisoning. Additionally, about 200,000 smallholder farmers have been displaced, triggering a 15% rise in urban slum populations (UNDP, 2023). Armed gangs routinely terrorize communities: in 2022, about 34 villagers in Dunkwa-on-Offin were hospitalized after resisting galamsey encroachment.

Projected Long-Term Impacts

If unchecked, galamsey will render Ghana’s ecosystems irrecoverable by 2030:

i. Total forest cover loss could reach 50%, triggering desertification in northern regions.

ii. Water scarcity may displace 10 million Ghanaians, sparking cross-border conflicts over the Volta Basin.

iii. Agricultural collapse could push 5 million into extreme poverty.

The evidence is irrefutable: galamsey is not merely an environmental crime but a existential threat to Ghana’s survival. The scale of devastation which is captured in satellite imagery, medical reports, and economic data demands not only urgent but uncompromising action.

Legal Framework for the “Shoot to Kill” Policy

- Constitutional and Statutory Basis

Ghana’s legal system provides robust grounds for the “Shoot to Kill” policy as a last-resort measure to combat the existential threat posed by militarized galamsey syndicates:

i. Article 13 and 41 (k) of the 1992 Constitution: Mandates the state to “protect and safeguard the national environment for posterity.” The scale of environmental destruction caused by galamsey evidenced by Figures 2-8 (in earlier pages) renders this policy a constitutional imperative.

ii. Public Order Act (1994), Section 2(1b): Covertly authorizes lethal force to prevent crimes that pose “imminent danger to life or property.” Armed galamsey gangs, which routinely engage in shootouts with security forces, meet this threshold.

iii. Minerals and Mining Act (2006), Section 99: Criminalizes illegal mining but lacks punitive measures proportional to the devastation caused.

International Law and Precedents

The policy aligns with global norms for extreme environmental crimes:

i. UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force (1990): Lethal force is permissible when “strictly unavoidable to protect life” (Principle 9). Over the years, galamseyers have killed some security officers , underscoring the lethal threat.

ii. Colombian Precedent: Colombia’s “Operation Artemis” (2019–2023) reduced illegal mining in the Amazon by 62% through authorized lethal engagement, saving 1.2 million hectares of rainforest.

iii. Kenya’s Anti-Poaching Model: Kenya’s shoot-to-kill order against ivory poachers in 2016 cut elephant deaths by 80%, demonstrating the efficacy of calibrated force.

Operational Protocols to Ensure Proportionality and Accountability

- Rules of Engagement (RoE)

The “Shoot to Kill” policy MUST follow strict, legally codified rules to prevent misuse:

Trigger Threshold: Lethal force ought to be authorized only when galamseyers:

i. Openly brandish firearms or explosives.

ii. Engage in acts of violence against security forces or civilians.

iii. Attempt to destroy critical infrastructure (e.g., bridges, water treatment plants).

De-escalation First: Security personnel must issue verbal warnings and use non-lethal measures (tear gas, rubber bullets) before resorting to lethal force.

Technology-Driven Accountability

i. Body Cameras: All officers must wear body cameras with real-time streaming to a central command center. Footage must be stored for 5 years and audited randomly.

ii. Drone Surveillance: Drones equipped with thermal imaging must monitor high-risk zones (e.g., Tarkwa, Obuasi) to document illegal activities and ensure compliance with RoE.

Judicial and Civil Oversight Mechanisms

Independent Review Committee (IRC)

A 7-member IRC must audit every incident of lethal force within 48 hours:

Proposed Composition:

2 judges (nominated by the Judicial Council).

2 civil society representatives (e.g., CHRAJ, Amnesty International Ghana).

1 religious leader.

1 military legal advisor.

1 environmental scientist.

Powers:

Subpoena body-cam/drone footage.

Recommend prosecution for protocol violations.

Publish findings on a public transparency portal.

4.3.2 Transparency Portal

A publicly accessible online dashboard should display:

i. Real-time updates on operations.

ii. Redacted body-cam footage.

iii. IRC investigation reports.

iv. Statistics on arrests, seizures, and casualties.

Ethical Training and Community Safeguards

- Pre-Deployment Training

All security personnel must undergo mandatory 3-week training on:

i. Human rights law (led by CHRAJ).

ii. Conflict de-escalation tactics.

iii. Environmental conservation ethics.

Certification: Only officers scoring 80% or more on post-training exams will be deployed.

Civilian Protection Measures

i. Community Sensitization: Monthly town halls in mining regions to educate civilians on:

Avoiding conflict zones.

Reporting illegal activities via a toll-free hotline.

ii. Compensation Fund: A $15 million fund must be established to compensate families affected by accidental casualties, managed by the Ministry of Gender and Social Protection.

Complementary Socio-Economic Interventions

- Alternative Livelihood Programs

Vocational Training: Ex-galamseyers must receive free training in sustainable trades such as:

i. Agroforestry (e.g., cocoa, bamboo farming).

ii. Solar panel installation.

iii. Eco-tourism.

iv. Startup Grants: $5,000 grants for green businesses, funded by mineral royalties.

Tech-Driven Environmental Restoration

i. AI Monitoring: Satellite systems with machine learning will detect and alert authorities to new mining sites in real-time.

ii. Rehabilitation Bonds: Mining firms must post $1 million bonds for land restoration before licensing.

Partnership with NGOs and International Bodies

i. NGO Monitoring: Amnesty International and Global Witness must conduct unannounced inspections of operations.

ii. UN Collaboration: Technical support from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) to refine protocols.

Conclusion

- “A Necessary Imperative for National Survival”

The galamsey crisis in Ghana is not merely an environmental issue but an existential threat that demands radical, lawful intervention. The evidence presented in this paper, spanning geospatial deforestation maps, toxicological water analyses, and harrowing accounts of armed violence paints a grim portrait of a nation teetering on the brink of ecological collapse. The proposed “Shot to Kill” policy, anchored in Ghana’s constitutional mandate to protect its environment and citizens, emerges as the only viable mechanism to dismantle the militarized networks driving this devastation.

The Cost of Inaction: A Nation in Peril

If Ghana continues its current trajectory, the consequences will be catastrophic:

i. By 2030, 50% of Ghana’s forests will vanish, accelerating desertification and biodiversity loss (Global Forest Watch, 2024),.

ii. By 2040, all major rivers will be irreversibly contaminated, displacing 10 million Ghanaians and triggering water wars (Ghana Hydrological Authority ,2024; Water Scarcity Projections (2024–2040).

iii. By 2050, agricultural collapse could push 30% of the population into extreme poverty.

The Efficacy of “Shoot to Kill”: Lessons from Global Precedents

International case studies underscore the policy’s potential:

i. Colombia’s Operation Artemis (2019–2023): Reduced illegal mining by 62 per cent and revived 800,000 hectares of rainforest (Recovered Rainforest in Colombia’s Amazon, 2023)

ii. Kenya’s Anti-Poaching Model (2016): Cut elephant poaching deaths by 80 per cent through calibrated lethal force (World Resources Institute, 2024).

Safeguarding Humanity Amid Harsh Measures

Critics argue that “Shot to Kill” risks human rights abuses, but Ghana’s stringent safeguards ensure proportionality and accountability:

i. Judicial Oversight: The Independent Review Committee (IRC) would investigate incidents when the policy is rolled out, prosecute officers for protocol breaches.

ii. Community Compensation: The $15 million fund would be disbursed reparations to 85 families affected by accidental casualties.

iii. Tech-Driven Transparency: Public access to body-cam footage and drone logs would build trust, with 78% of Ghanaians supporting the policy.

A Blueprint for National Renewal

The policy’s success hinges on parallel socio-economic interventions:

i. Alternative Livelihoods: Over 3,000 ex-galamseyers would transitioned to agroforestry and solar tech, reviving 5,000 hectares of degraded land.

ii. AI Monitoring: Satellite systems to detect illegal mining in real-time, enabling rapid response rates of about 92%.

A Call to Conscience and Action

Ghana stands at a crossroads: succumb to environmental annihilation or reclaim its future through courageous, lawful action. The “Shot to Kill” policy, though severe, is a moral imperative to protect the rights of future generations to clean water, fertile land, and a stable climate. After all, as PATRIOTIC GHANAIANS, we do not only sing or chant, but strong believe in the lerics,

“Y3n ara y’asase ni, 3y3 abo)denden ma y3n,

mmogya na nananom hwie gu nya de to h) maa y3n.

Aduru me ne wo nso so, s3 y3b3y3 bi atoaso…”.

Final word

The time for half-measures is over. Ghana must act decisively, leveraging every legal and technological tool to dismantle galamsey’s stranglehold. With robust safeguards and global solidarity, this policy proposal can forge a legacy of renewal—one where forests regrow, rivers run clean, and communities thrive.

The author is Collins Tetteh Abeni, Acting College Registrar, Offinso College of Education (0202 233 902/ 0261546102)