A seemingly ordinary romance between a young American intelligence officer and her Ghanaian lover in the early 1980s spiralled into one of the most significant espionage scandals in United States–Africa relations during the Cold War.

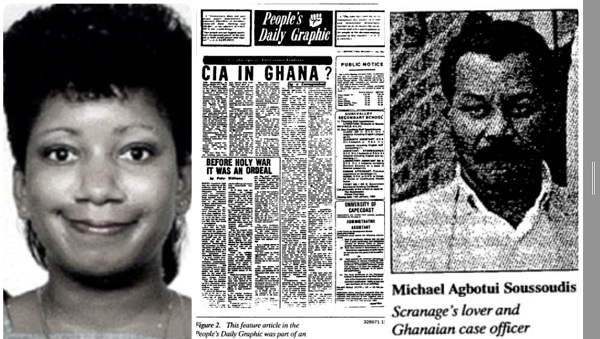

The case of Sharon Marie Scranage, a CIA stenographer stationed in Accra, exposed a dangerous breach of American intelligence operations and sent shockwaves through both Washington and Accra.

Sharon Scranage, a native of Virginia, joined the CIA in the late 1970s as a support clerk. In 1983, she was posted to Ghana, then under the rule of Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings and the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC). The United States and Ghana had a complex relationship at the time, cautious and often mistrustful but gradually improving after years of political tension.

While stationed in Accra, Scranage met Michael Agbotui Soussoudis, a Ghanaian businessman with close links to the PNDC’s intelligence establishment and a reported cousin of Rawlings. Soussoudis was charismatic and well connected, moving easily within Ghana’s elite social circles. Their relationship, initially viewed as a private romance, soon became an espionage channel that would compromise dozens of CIA operations in West Africa.

According to U.S. court documents and testimonies declassified by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Scranage began passing classified information to Soussoudis shortly after their relationship deepened. The leaked materials included the identities of CIA operatives, local informants, and details on U.S. intelligence-gathering methods in Ghana and neighbouring countries. She also disclosed information on communications networks, radio frequencies, and military-related intelligence.

Her betrayal came to light in 1985 after she returned to the United States and underwent a routine CIA polygraph test, a standard requirement for officers completing foreign assignments. The test results were alarming, described by one CIA official as having “gone off the chart.” When confronted, Scranage confessed to leaking classified materials to Soussoudis.

The confession prompted a swift FBI operation. Working with the CIA, U.S. authorities arranged a sting to lure Soussoudis to the United States. He was arrested in a motel in Virginia on July 11, 1985. The following day, Scranage was also taken into custody and charged with espionage.

The revelation caused a diplomatic storm. Dozens of CIA officers were forced to leave Ghana immediately. Robert E. Fritts, who was the U.S. Ambassador to Ghana at the time, described the crisis as “a first-class spy flap.”

In a later interview, he recounted that the embassy had to be “hunkered down” amid fears that Ghanaian security forces might retaliate against suspected CIA informants. “It was a very extensive and serious compromise, including far beyond just Ghana,” Ambassador Fritts said.

According to him, “Scranage was seduced physically and morally by the glamour of being selected to go where no other Western foreigner went.” He added that Soussoudis had exploited her loneliness and grievances, hosting lavish parties and drawing her into Ghana’s elite social scene.

The scandal not only led to the exposure of CIA networks but also risked the lives of Ghanaian nationals who had cooperated with U.S. intelligence. Ambassador Fritts recalled that, fearing reprisals, “we progressively evacuated all the Americans associated in any way, as well as those not associated if Scranage said she had mentioned them. The exodus was an all-hands embassy effort.”

In Washington, the U.S. government faced embarrassment as media reports described a love affair turned spy saga. Both Scranage and Soussoudis were charged with espionage. Scranage cooperated with investigators, leading to a plea deal. In November 1985, she pleaded guilty to violating espionage laws and was sentenced to five years in prison, although she served less than half before being released for good behaviour.

Soussoudis, meanwhile, was convicted in the United States but became the centre of a tense diplomatic negotiation between the two governments. Ghana arrested several of its nationals accused of spying for the U.S. in retaliation. After months of talks, both countries agreed to a spy swap. Soussoudis was deported to Ghana in exchange for the release of several detained Ghanaians linked to the CIA.

The exchange took place quietly on the Ghana–Togo border but not without controversy. Photos of the exchanged individuals embracing American officials were leaked to the Ghanaian press, fuelling anti-U.S. sentiment. Ambassador Fritts later admitted that “it was not a good press day for the United States in Ghana.”

Ambassador Fritts, who left Ghana in 1986, later reflected that the bilateral relationship had gone “from a pit to a pinnacle and was now back in a pit.”

The case of Sharon Scranage remains a striking example of how personal relationships can unravel the intricate web of international intelligence. For the CIA, it became a cautionary tale about the vulnerabilities of human emotion in espionage work. For Ghana, it was a moment that highlighted its growing geopolitical relevance during the Cold War.

Nearly four decades later, the story still resonates as one of the most sensational espionage cases in Africa, a tale of love, betrayal and the dangerous intersection between romance and geopolitics.