2018 Deficit is 7.2%, not 3.7% of GDP, Seth Terkper asserts

The annual 2018 Debt Management Report submitted to Parliament includes a key update of Ghana’s end-2018 budget deficit.

Other updates in March 2019, after the passage of the 2019 Budget, included the IMF Board Report on the ECF Program (7th & 8th Review) and the Minister’s Statement to Parliament.

The disclosures facilitate transparency and better analysis and understanding of our fiscal situation.

The Debt Report states (p. 26; par 31) that“ “The provisional budget deficit outturn for 2018 (excluding the financial sector bailout) was GH¢11,672.4 million (3.9% of GDP), slightly higher than target—on account of lower than expected revenues, relative to expenditure.

Including financial sector clean-up costs, however, the provisional budget deficit was GHc21,474.0 million (7.2% of GDP)”.

The report, which MOF must submit to the House annually by end-March under the Public Financial Management Act, 2016 (Act 921), also puts the end-2016 deficit at 6.5 per cent of GDP.

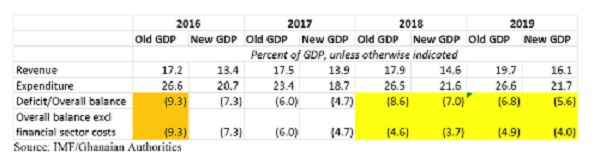

The IMF report that signaled our exit from the IMF Programmes (not membership) puts the end-2018 fiscal deficit at 7 per cent of GDP and the end-2016 deficit at 7.3 percent.

The irony

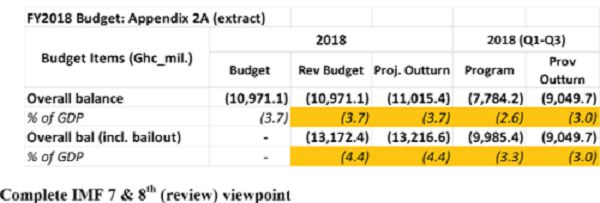

The deficit of 7.2 per cent is higher than the firm assertion of 3.7 per cent in the 2019 Budget, with additional GH¢2.2 billion bailout costs embedded in Memorandum (Appendix 2A) that increases the deficit to 4.4 per cent.

It is instructive to note that, the 3.9 per cent in the 2018 Debt Report is in the Finance Minister’s March 2019 Statement.

Ironically, the 7.2 per cent deficit is higher than the end-2016 deficit of 6.5 per cent that the government continues to berate as excessive—even when it includes (a) “arrears” of GH¢5 billion (3 per cent of old GDP) that was “offset”, not paid; and (b) reversal of “cut-off” rules to allow January FY2017 payments to accrue to FY2016 expenditures in the 2017 Budget.

The prevailing economic situation in FY2016 and 2018 differ: the global financial crisis, single oil field, and precipitous fall in crude oil price against modest recovery, three oil and gas fields, significant increase in crude volumes and prices as well as reserves in the stabilisation/Sinking Fund (to reduce debt) and ESLA flows (to support resolution of the banking crisis).

Position in 2§019 Budget and Special Statement

In the 2019 Budget, the Minister seemed keen to use the pre-2018 (old GDP)) to elicit applause.

“The fiscal deficit was reduced from 9.3 per cent of GDP in 2016 to 5.9 per cent in 2017 (the first time since 2006 that a government has met the deficit target), it is at 2.8 per cent of GDP in June 2018, within the target of 4.5% of GDP in December 2018” (p.5, par. 19).

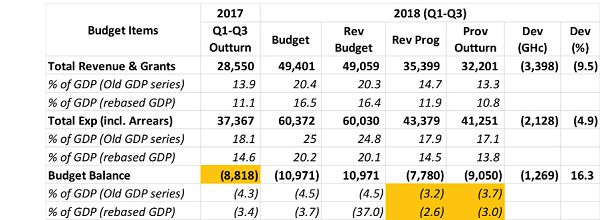

As noted in Table 1, however, the same Budget shows the projected “narrow” rebased deficit as 3.7% of GDP (cash basis) for Q1-Q3 (Budget Table 5, p. 39, par. 166).

Table 2 shows the bailout costs and “broad” end-2018 fiscal deficit of 4.4% in the Memorandum (Appendix 2A, p. 200) while the MOF Fiscal Tables show a deficit of 3.7% (Ghc10,971) as Provisional Outturn and revises the Q1-Q3 actual downwards to 3.2% or GH¢9,566 (www.mofep.gov.gh).

CIMF viewpoint

The Finance Minister stated emphatically in the March 2019 Statement that the IMF Board commended government’s fiscal performance.

“Mr. Speaker, the Executive Board … commended the Akufo-Addo Government for putting the Programme back on track and achieving significant macroeconomic gains over the course of the ECF supported program, which has resulted in … (c) accelerated fiscal consolidation with contraction of over 3 per cent of rebased GDP (i.e., 7.3% (2016) to 3.9 per cent (2018)”—p 5, par. 14[c].

However, the Minister did not mention the Fund’s “Overall Balance” estimate as seven per cent—and the Overall balance (excluding bailout costs) of 3.7 per cent as only secondary.

The Fund states in Footnote 6 (IMF 7/8th Review Report, p. 14 par 16): “The analysis is complicated by the fact that the GDP rebasing [sic] affected past years differently; in addition, not all financial sector costs are reflected in the above-the-line fiscal accounts (as some represent equity injections below the line), though they are all included in public debt.”

Besides a call for consistent treatment of exceptional fiscal items, the complication is not material to our need to plan to finance the total deficit of 7.2 per cent through raising more revenues or borrowing—if we do not want to encourage “off-balance sheet” treatments.

Table 3 and Figure 1 show the IMF’s revenue, expenditure, and fiscal or budget deficit outcomes and projections from FY2016-FY2019 (IMF Report p14, par 16).

Bailout costs

The closest the government has come to explaning the IMF’s footnote is isolating the borrowing for bailouts in the Debt Report (p22, par. 21)— underpinned fully or partially by ESLA inflows (levies) and outflows to repay the [ESLA] Bonds.

“Public debt stock as at end-December 2018 was GH¢173.068.7 million (US$35,888.5 million), representing 57.9 per cent of rebased GDP.

A large part of the 2018 debt additions resulted from the financial sector bailout programme of Government (footnote 1 here).

The cost incurred by the government to clean the financial sector impairments resulted in the public debt increasing by 3.2 per centage points of GDP in 2018. Excluding the bailout costs, however, the stock of debt amounts to GH¢163,487.5 million (US$33,901.7 million) representing 54.7 per cent of GDP as at end-December 2018.”

I agree with using “footnotes” or “memos” to explain gross amounts but disagree with changing the fiscal rules for exceptional costs in a conventional “cash accounting” (receipts and payments) framework for two political regimes under the same IMF ECF Programme (2015-2019).

It is unfair, distortionary and inconsistent to use a “broader” definition of “arrears” and separate capital (i.e., assets, liabilities, and equity (Balance Sheet) and recurrent flows (Income Statement) for one and not the other.

Ghana prepares the fiscal tables on “cash-basis” and adjusts for arrears under the IMF Programme Technical Notes—which appear to ignore the compilation of “long-term” liabilities for MDAs in an effort to shift to a GIFMIS “semi-accrual” basis in 2016.

Nonetheless, I note the following recent fiscal rule changes to the fiscal rules

offset of arrears: adding GH¢5 billion arrears to cash expenditures which increased only FY2016 deficit (commitment basis)—later offset in the arrears portion of the fiscal tables to achieve a lower deficit (cash basis);

energy sector subsidy: adding subsidies relating to the power crisis to arrears fully (2012-15)—leading to enactment of ESLA and the first financial sector bailout costs in 2016;

single-spine migration costs: accruing and paying huge budget overruns (FY2010-15) relating to the wage rationalisation that initiated in FY2008;

grossing-up of refinancing costs: adding the 2015 World Bank-guaranteed Bond of GH¢1 billion, used entirely to refinance existing debt, to total public debt—and abated only after their use in FY2016;

deficit and financing identity: the outcome of some of these changes affecting the normal deficit and financing identity as well as fiscal relations between deficit on commitment and cash basis.

Conclusion—resolution in PFMA Regulations

MOF must explain the full details and impact of the bank bailout costs on the fiscal situation in the country.

I note that senior officials use the 3.7 or 3.9 per cent to tout fiscal consolidation and deliberately excluding 7.2 per cent disclosed within three (3) months of Parliament approving the Budget—in the Minister’s Special Statement, IMF Report and the 2018 Debt Report.

In the past, Ghana added all exceptional costs—including single spine, subsidy, bank bailouts, resolution of power crisis, and impact of commodity prices changes—to arrears to determine the fiscal deficit (cash basis), borrowing, financing and public debt (domestic and external).

We can use the passage of the PFMA Regulation in Parliament now to move from “cash” to a more mature “semi-accrual” basis.

However, we must do so under very clear, not arbitrary, “cut-off” rules which (a) make reasonable adjustment for prior years, as is the practice with rebasing; or (b) use the end of the IMF Programme to make the switch. Examples of the rule change must include:

accounting standards: having adopted IPSAS in 2015, the Institute of Chartered Accountants, Ghana (ICAG) and Controller must prepare and publish the relevant national guidelines for preparing the Budget and Public Accounts;

semi-accrual accounting: a national standard must move to semi-accrual basis by fully activating the Accounts Payable module in GIFMIS (and Contract Database in MOF) to correct all “offsets” to date, including FY2016 GH¢5 billion liability;

cut-off rules: we must establish firm “cut-off” rules to avoid the discretionary reversals of accounting records, as occurred in FY2017 without following it consistently;

exceptional items: we must establish the fiscal rules to distinguish items that form part of GIFMIS general ledger and those that appear as notes or memoranda to the Public Accounts and Fiscal Tables; and stock versus flows: the PFMA Regulations must state the obvious to avoid instances such as the use of end-March 2017 foreign exchange rate to calculate end-2016 debt balance—an approach that offends best practice under the IMF Government Fiscal Statistics (GFS).

As a country, we have an opportunity to do the right thing. We must collaborate with the sponsors of GIFMIS (World Bank, IMF and donors) to use the ongoing discussions in Parliament on the PFMA Regulations to establish firm fiscal rules for revenue, expenditure, deficit, borrowing, and debt in our budgets and fiscal tables.

The writer is the immediate past Minister of Finance and lead consultant at PFMA Tax Africa