Standards-based curriculum implementation: What’s working?

In September 2019, Ghana began to implement the pre-tertiary standards-based curriculum, a curriculum system implemented by many developed countries across the world.

A unique characteristic of the standards-based curriculum is its precise calibration of student knowledge and competency at each grade level, known as content standards or grade-level expectations.

Therefore, upon its adoption, our basic education system is being guided by a carefully designed body of knowledge, skills, values and core competencies.

Standards-based curriculum

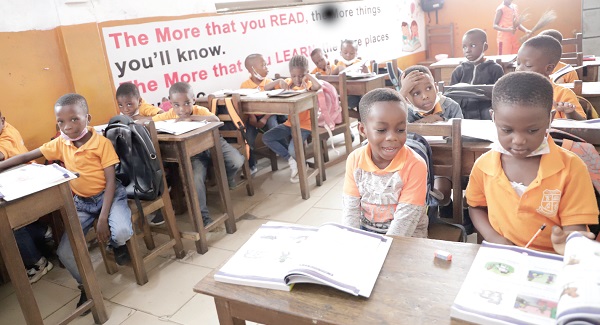

The introduction of the standards-based curriculum was also intended to alter how teachers teach, emphasising the utility of creative, inclusive pedagogies and improved classroom assessment practices.

This is to enable schools to increase students’ interest in learning, engaging them deeply and meaningfully in rich, rigorous content that will adequately prepare them for national development in a rapidly changing global environment.

After three years of implementing the standards-based curriculum, I observe that sections of the public seem to have limited knowledge of this curriculum model and its effects.

As an education policy consultant and former director-general of the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NaCCA) under whose tenure the implementation began, I feel obliged to reflect on the reform initiative to highlight its key imperatives, implementation successes and areas for improvement.

Imperatives

Today, under the leadership of President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, a new globally recognised curriculum is operational in Ghana, which aims at creating critical thinking, digitally savvy Ghanaian students with the potential of becoming civically responsible citizens poised to build our nation.

The standards-based curriculum begets many positive outcomes for our education system. First, we have the opportunity to improve education delivery through carefully crafted standards — developed by education sector experts, including teachers, researchers, consultants and advocacy groups — that better appraise each student academically, emotionally and socially.

Today, parents and stakeholders can reference these standards to assess the development of students.

Furthermore, we have, by this reform, renegotiated our curriculum modelling to favour higher-order thinking, rather than rote learning and memorisation, while focusing on cross-curricular content that progressively integrates learned knowledge.

What is working?

A nationwide effort to implement the pre-tertiary standards-based curriculum for kindergarten to Basic Six (i.e., KG-B6) was launched at the opening of the 2019/2020 academic year in September 2019.

Before that, all 152,000 KG-B6 teachers tasked with effectively implementing the new reform were informed and trained on the curriculum change, its policy expectations and teachers’ requirements, at various district-level training centres across the country.

Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) for teachers were also established to sustain the process of professional development for the teachers.

The PLC is a novel introduction, a mentoring and peer-learning community for teachers in the same school and district to provide further professional learning opportunities that are outcome-oriented. Admittedly, the implementation of PLCs is bedevilled with some challenges and will be discussed in the subsequent piece.

Three years after implementation, teaching seems to be better guided by the new ideas and visions of the curriculum, including how schools operate. There is a good level of acceptance among regional and district staff, headteachers and teachers for the change, which gives strong indication that with adequate support, the reform will be successful.

The quality of teacher delivery is evidenced to be improving, with indications from implementation pointing to an increasing use of learner-centred and interactive teaching approaches, including group work and cooperative learning strategies.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation’s (UNESCO) Ghana Spotlight Report in 2022 shows that teachers in the rural areas of the Upper West Region, for example, are improvising in the use of teaching and learning resources.

One can then infer that these improvisations have been motivated by the expectations of the new curriculum.

I am, however, unable to conclude on how pervasive these practices are across the country given the lack of evidence, but some headteachers have given positive feedback.

What is working, for me, is the Ministry of Education’s approach to using stronger performance expectation tied to the signing of performance contract, KPIs at the regional and district education levels.

Further, there appears to an increased focus on literacy and numeracy, which is fostering improvements in learning outcomes.

The UNESCO’s Ghana Spotlight Report in 2022 confirms these claims, but also shows that one cannot disassociate the impact of the Ghana Accountability for Learning Outcomes Project (GALOP) interventions on the gains so far.

The use of Teacher Resource Packs (TRP) – as teacher manual, which accompanied each subject curriculum – in planning instructions is likely having a transformational impact on teacher preparation and capacity to deliver the curriculum.

The implementation of the NST for Basic Four pupils in December 2021 is remarkable even though it is a partial fulfilment of the assessment plan and priority.

The NST was born from the development of the National Pre-tertiary Learning Assessment Framework (NPLAF) to encourage learner-focused assessments and monitor students’ attainment of educational standard in Basic Two, Basic Four, Basic Six, Basic Eight and Basic 11.

Instructional resources and textbooks have new approval expectations. Approved instructional materials and textbooks provide a wide variety of content that effectively support implementation by encouraging critical thinking and enriching the learning experiences for students, as well as creatively contributing to the pedagogy of teachers.

Conclusion

My reflection on this matter is not exhaustive, but these aspects of the implementation of the standards-based curriculum are worth highlighting.

Generally, there are always disparities between policy objectives and actual policy outcomes owing to implementation inefficiencies and unintended developments.

Hence, the challenges faced in the implementation of the new curriculum are natural and expected. The positive outcomes, however, have far outweighed the challenges.

The writer is the MP for Kwesimintsim, and Vice Chairman of the Parliamentary Select Committee on Education. A former Director-General of NaCCA, a lecturer and education consultant to the World Bank, UKAID, USAID and UN Education Commission-funded projects in Ghana. www.princeharmah.com