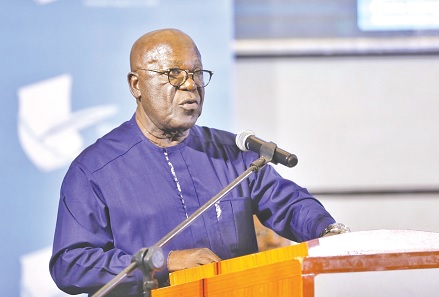

Sam Jonah advises architects to harness local resources

Renowned business executive, Sir Sam Jonah, has challenged local architects to fashion out a new building model that harnesses local resources, culture and climate, but still boasts structural resilience and possesses the beauty of the Ghanaian system.

“Architecture must reflect local culture, climate and context. It must withstand natural disasters and climate change. It must reflect community values and aspirations. It must promote beauty, harmony and human flourishing,” he said.

Addressing the Ghana Institute of Architects in Cape Coast in the Central Region last Friday, Dr Jonah charged members of the institute to lead efforts to reshape Ghana’s built environment with recommendations for suitable designs and complementary materials that not only reflected the identity of the people, but also were suitable for the environment.

In a speech that travelled cultures, systems, climatic conditions, concepts, attitudes, time and people, Sir Sam suggested a strong consideration for Ghana’s peculiar climate, its architectural history and traditions, and a fusion with technology and modernity into a blend that gave identity to local designs and building culture.

Relevant elements

For example, he said, local architectural designs must factor in temperatures, the habitat, costs, and other relevant elements to ensure sustainability for both the users and the environment.

“Let us stop replacing louvre blades with fixed glass that blocks fresh air, only for the air conditioners to run for hours.

Fresh air is not the enemy.

If anything, it is cheaper than your client’s ECG (electricity) bills,” Dr Jonah said.

“Let us build a Ghana where architecture reflects culture and context, not imitation and imports,” he added.

Referring to the theme of the event: “From Castles to Our Future Cities”, Dr Jonah described it as both timely and provocative, a reminder that “architecture is never neutral”, and the fact that it reflected “the values, priorities, and power dynamics of the societies that build it”.

He asked: “Have we forgotten how to build for our climate, our culture, our context? Are we content to mimic the opulence of Dubai while neglecting the earthiness of Dodowa?

Are we happy to import cement endlessly — despite having no clinker production — while ignoring the genius of our ancestors who built sustainable, breathable habitats from mud, timber and laterite?”

Examples

Dr Jonah, who steered AngloGold from full state-ownership into a multi-million-dollar private multinational enterprise, cited new paths in Burkina Faso and Kenya to drum home his belief in a localised architectural engineering regime.

“Across Africa, others are showing the way. In Burkina Faso, mud is a medium of architectural glory. In Kenya, bamboo is being moulded into structural poetry.

Why then is Ghana — blessed with natural materials — still committed to soulless, indistinguishable concrete boxes?

“The Japanese have a minimalist elegance rooted in Zen.

The Chinese blend ancient form with futuristic ambition. The Koreans balance nature with high-tech harmony,” he said, and asked: “What will Ghana’s future architectural identity be?”

“Examples such as The Unisphere in Maryland, The Edge in Amsterdam, the NUS School of Design in Singapore, and the Z6 Tower in Beijing demonstrate what is possible when sustainability meets ambition.

“I am not asking you to imitate blindly. I am asking you to select intelligently what works for our climate and fuse it with our cultural identity.

“Masdar City in Abu Dhabi — hotter than Tamale — is pursuing a 644-hectare net-zero development.

What excuse do we have? Let us commit to designing buildings that generate as much energy as they consume,” he added.