Ideological rivalry heralded independence

Ghana became independent on March 6, 1957, after two ideologically rival parties had heralded a political struggle that has sharply divided the country’s democratic evolution along ethnic and political lines in the post-Second World War period.

The parties were the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC), formed in August 1947, and the breakaway Convention People’s Party (CPP), formed in June 1949.

The formation of the UGCC in particular was largely precipitated by the shortcomings of the colonial government, which neglected the welfare of the indigenes.

The end of World War II in September 1945 basically marked the beginning of an epoch when political activities and organisation were mainly the exclusive preserve of the elite.

That situation pitched the interests of the wider section of the population, especially urban workers, demobilised soldiers and cocoa farmers, against the interests of the colonial power structure.

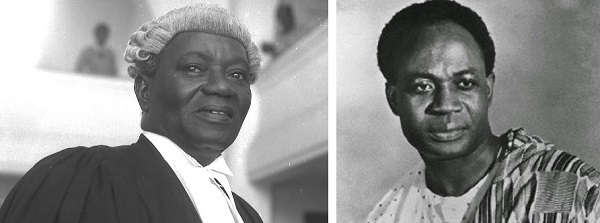

The UGCC was led by Dr J. B. Danquah, a lawyer, anthropologist, philosopher and politician.

The aim of the party was to ensure “that by all legitimate and constitutional means, the direction and control of the government should pass into the hands of the people and their chiefs in the shortest possible time”.

But unable to devote their full time to party organisation, the lawyers and businessmen who formed the UGCC invited Kwame Nkrumah to become the General Secretary of the UGCC.

Nkrumah’s assumption of office as General Secretary of the UGCC in 1947 was certainly an important turning point in the history of the party and Ghana as a whole.

Radical organisation

Not only did his assumption of office boost the party; it also provided a focal point for radical organisation, which development eventually led to his breaking away from the UGCC to form his own party, the CPP.

The outbreak of anti-colonial riots in 1948 brought into sharp focus the ideological and political contradictions between Nkrumah and the rest of the conservative UGCC leadership.

As a result, Nkrumah’s supporters within the Committee of Youth Organisations (CYO), which he had established within the UGCC, compelled him to break away to form the first mass political organisation in the country, the CPP, on June 12, 1949.

The CPP won the general elections of 1952, 1954 and 1956.

The elections of 1954 witnessed the formation of political parties along regional and ethnic lines. For example, the Northern People’s Party (NPP) was formed out of fear among the people of the Northern and Upper regions, especially the educated people and chiefs, that they would be dominated by the people of the south after independence.

Its aims, among others, were to win respect for the culture of the people of the northern territories to ensure their just treatment, protection against abuse and their political and social development.

Ethnic parties

Closely connected with the NPP was the Muslim Association Party (MAP), formed in 1954 out of the Gold Coast Muslim Association established in the early 1930s.

As the name indicates, it was formed primarily to cater for the interests of Muslims living in the Zongos (Muslim quarters) of the main towns in the country.

The CPP won 72 out of the 104 seats in 1954; NPP 12, GCP one, MAP one, while AYO and the TC won one and three seats respectively.

The CPP won by a clear majority, and also won seats in all the regions of the country — 38 in the colony, 18 in Ashanti, eight in Trans-Volta and eight in the North.

Asante nationalist movement

However, three months after the 1954 elections, the National Liberation Movement (NLM) emerged, started and essentially remained as an Asante nationalist movement, with its leadership concentrated in the hands of the Ashanti people.

The NLM, according to its Founder, Baffour Osei Akoto (also a senior linguist of the Asantehene and father of the current Minister of Food and Agriculture, Dr Owusu Afriyie Akoto), was an attempt by the Ashanti to safeguard its national identity and reverse the trend that threatened its traditional institutions with extinction.

The aims of the NLM were couched in general terms to be applicable to the whole of Ghana.

The rise of the party affected the subsequent history of Ghana in two ways — it began an era of violence, arson and anarchy which reigned in Kumasi and its immediate environs for about three years and also raised questions as to what kind of constitution independent Ghana should have and whether there should be any fresh elections before independence or not (Asante & Gyimah-Boadi, 2004).

While the NLM maintained preference for a federal constitution, the CPP insisted that the constitution should be unitary.

Fresh elections

On the question of fresh elections, the NLM argued that since it had just emerged after the 1954 elections, there should be a new general election to determine which of the two parties — the CPP and the NLM — was more popular.

It is against that background that the final lap in the battle for independence began with the general election of July 1956.

The election was to determine the preference of Ghanaians in terms of the timing of political independence from British colonial rule. The CPP won all the 44 seats in the colony (Asante & Gyimah-Boadi, 2004).

Secessionist moves

The first reason for the CPP’s success in the 1956 elections was the weakness of the opposition parties.

Secondly, the battle cry for federation and ‘mate me ho’ (secession) of the NLM and its allies, scared a large number of voters elsewhere. Although some people were anti-CPP, they were nevertheless opposed to federalism and secession.

The propaganda mounted by the CPP, highlighting the threat of the re-establishment of the Ashanti domination over the country in the event of an NLM victory, also proved particularly effective in southern Ghana.

In addition, the NLM concentrated too much on Ashanti, Akyem and sections of the Northern Region.

CPP weakened

Although the CPP won the 1956 elections, the results showed that it was quite weak in the Ashanti, Volta, Northern and Upper regions.

On the basis of that, Dr K. A. Busia and the opposition, immediately after the release of the final results of the elections, announced that the results justified the NLM’s call for a federal form of government, arguing that although the elections had been fought over the issue, the CPP could not win overall majority in both the Ashanti and the Northern territories, for which reason there was no alternative but federalism (Nkrumah, 1972).

Antagonism was also developing in the various regions based on sectional interests, in spite of the May 1956 plebiscite that was conducted by the UN to find out whether the then British Togoland (made up of the Trust Territories, now Volta Region and parts of the Northern Region) wanted to join the Gold Coast, and the fact that the CPP, which campaigned for the area to join the Gold Coast, won 79 per cent of the votes cast in favour of the union.

The people of southern Togoland were still in open rebellion and even boycotted the independence celebrations.

Tension in Accra

Similarly, in Accra, tension between the CPP and the Ga people grew worse and led to the formation of the 7777/Ga Shifimokpee (the Ga Standfast Association) in 1957.

That movement later joined forces with the opposition groups.

The antagonism was further worsened when, after boycotting the legislative assembly, the opposition sent a delegation to London to press the case for a federal form of government.

The constitutional crises were later on defused by the intervention of the British government, which succeeded in persuading the parties to make a concession in their respective demands.

Consequently, both parties agreed and regional safeguards were included in the Independence Constitution of 1957.

Even though the Independence Constitution maintained the unitary state, it also conceded a greater measure of administrative power to the regions through the creation of the Regional Assemblies.

It is against this backdrop that the Nkrumah-led CPP government introduced a number of harsh and radical political measures, in an attempt to deal with mounting ethnic tensions which threatened to disintegrate the country.

Regional lines

The measures started innocuously with the passage of laws forbidding the formation of political parties along ethnic, religious and regional lines (Avoidance of Discrimination Act, December 1957), which served to suppress all existing parties that had raised the question of federalism, such as the NLM and the Togoland Congress Party.

Indeed, the dissolution in March 1959 of the quasi-federalist interim regional assemblies established under the 1957 Independence Constitution appeared to have put a permanent lid on the issue of federalism and, to some extent, decentralised local government.

City Council

Furthermore, the CPP suspended the NLM-dominated Kumasi City Council and ordered a probe into its activities, apparently to break the hold of the NLM in Kumasi.

Nkrumah also appointed CPP politicians as Chief Regional Commissioners, in place of civil servants who were all British. That was done to strengthen the CPP in the regions.

He also introduced the Emergency Powers Act in January 1958 and separated the Bono-Ahafo area from the Ashanti Region and created it as a separate region, with its own House of Chiefs, and also went on to recognise a host of chiefs, who were pro-CPP in Ashanti, as paramount chiefs.