New malaria vaccines helped Ghana slash child deaths. Then Trump, others cut aid

New vaccines are helping Ghana approach a long-sought goal of ending child deaths from malaria, demonstrating the potential of the shots to drive back a disease that kills nearly half a million young children every year in Africa, according to the international vaccine aid group Gavi and the country’s health service.

But aid cutbacks by the Trump administration and other wealthy governments could mean fewer children benefit on the continent where malaria hits hardest, Gavi told Reuters.

Ghana is among the countries that had already made significant progress reducing malaria mortality by scaling up interventions such as the distribution of bed nets treated with insecticides and improving access to both preventive drugs and prompt treatment.

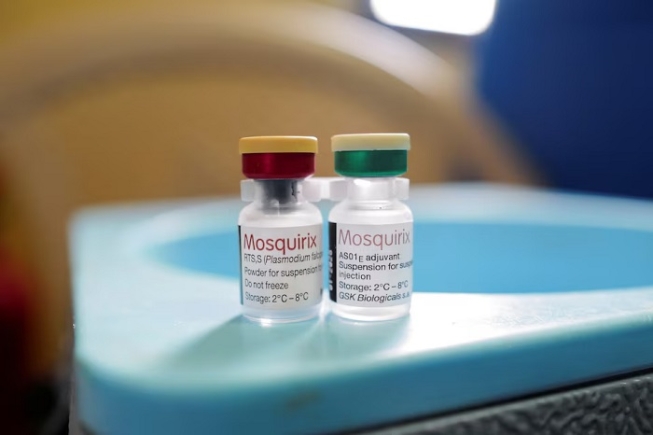

Two new vaccines - one developed by British drugmaker GSK (GSK.L), the other by Oxford University and the Serum Institute of India - are helping close the remaining gap, said Dr Selorm Kutsoati, who heads Ghana’s immunisation programme.

“For me, the malaria vaccine is a gamechanger,” she told Reuters.

Gavi is currently the only organisation purchasing malaria shots for African nations. It anticipates it will be able to spend just over $800 million on the programme over the next five years - 28% less than the expected need - after falling $2.9 billion short of its overall funding goal for the period, according to internal estimates prepared for its board of directors in December, seen by Reuters.

An additional 19,000 lives could be lost as a result due to lower vaccination rates, the documents say. The estimate, which has not previously been reported, is based on modelling of the vaccines’ impact by researchers at Imperial College London and the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute.

“It is the gap between the promise and the need for the vaccine, and the resources we have to provide that,” Scott Gordon, who heads Gavi’s malaria program, told Reuters.

U.S. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy announced in June that Washington would no longer support Gavi, part of sweeping cuts to foreign aid that President Donald Trump says do not align with his “America First” agenda. The United States was previously one of the group’s top donors, contributing some $1.3 billion between 2020 and 2024.

The U.S. "remains committed to working with global partners to combat malaria," a Department of Health and Human Services official told Reuters.

But the Trump administration will not disburse funds to Gavi unless it starts phasing out vaccines containing the mercury-based preservative thimerosal from its portfolio, the official said. Anti-vaccine groups have linked thimerosal to autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders, despite multiple studies showing no related safety issues.

Gavi confirmed the request and said the group remained in contact with the U.S. government on the subject. Any decision related to its portfolio would be "guided by scientific consensus," it said.

Other donors have also been scaling back support. Britain, Gavi’s biggest donor, has pledged 1.25 billion pounds ($1.72 billion) over the next five years, more than 20% less than for 2020-25.

Britain's international development minister, Jenny Chapman, said the country remains committed to supporting Gavi's work because it saves lives.

A MOTHER DECIDES: ‘I HAVE TO GO FOR THE VACCINE’

Some major global organisations initially doubted the potential of the two vaccines now being rolled out in 24 African countries with help from Gavi.

Based on clinical trials, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates they reduce malaria cases by over 50% during the first year after three shots are administered, an efficacy rate lower than many commonly used childhood shots. A fourth dose is required before a child turns 2 to maintain protection.

Supporters of the vaccines point to the success in Ghana, saying even a partially effective shot has translated into many lives saved.

“In real-world settings, we're seeing significant impact," Gavi’s Gordon said.

Confirmed deaths among children under the age of 5 have dropped nearly 86% in Ghana, from 245 in 2018, the year before GSK’s vaccine was introduced in select districts, to 35 in 2024, according to government figures. A decade ago, nearly 1,000 children in that age group died each year, Kutsoati said.

Malaria infections have also declined, from roughly 6.7 million in 2018 to 5.3 million in 2024, around a fifth of which were among children under 5, Ghana’s figures show.

The actual numbers are likely to be higher, as many malaria cases do not get diagnosed, and deaths that occur at home often go unreported, said Dorothy Achu, the WHO’s team lead for malaria in Africa. There can also be inconsistent reporting by some health facilities.

But Achu agreed the combination of strategies used in Ghana resulted in a “significant reduction in malaria deaths”, adding the WHO is using the country’s figures to update its estimates.

Esther Kolan, a 31-year-old clothing trader, did not need much persuading to get her 1-year-old son Phenehas Gyngyi Jr. vaccinated last summer at the Mother and Child Hospital in the southern town of Kasoa.

Her brother died of malaria just before his 15th birthday. A daughter was hospitalised twice with the disease before she turned 3.

“I told myself, no matter the condition, I have to go for the vaccine,” Kolan said, adding her family also sleeps under bed nets.

Phenehas has had three doses and has never been hospitalised with malaria.

“This has really helped me a lot,” said Kolan, who plans to get him a booster shot soon. “I was not scared for my child.”

Malaria deaths were already declining in their district when vaccines became available in 2023, according to Stanley Yaidoo, the municipal health services director. But the number of cases still put pressure on hospitals, exhausting staff and taking up beds that could be used to treat other dangerous diseases, he told Reuters.

“The vaccine implementation was the master stroke that we needed to support the already existing interventions,” Yaidoo said.

PROGRESS AGAINST A KILLER DISEASE

Some regions managed to eliminate malaria without a vaccine, but countries in sub-Saharan Africa face particular challenges, disease experts say.

Many are among the world’s poorest, with poorly-resourced health systems. The prevailing strain is particularly deadly, and there is growing resistance to preventive and curative drugs. Control efforts have been disrupted by conflicts and natural disasters.

The first countries to use the vaccines - Kenya, Malawi and Ghana - were part of a WHO-led pilot programme that began in 2019 with GSK’s shot. The WHO approved this vaccine for wider use in 2021, but the rollout faced hurdles, including a vast supply shortfall.

Access improved when WHO recommended the Oxford shot in 2023.

In many countries, it is too early to assess the vaccines' impact. But there are anecdotal reports of reductions in cases, hospitalisations and deaths among young children, according to the Gavi documents and interviews with health officials in four countries.

Take-up of the vaccines has varied, the documents show. In the first six months of 2025, coverage rates across 11 countries for three doses ranged from over 70% in Ghana and Burkina Faso, to 45% in Liberia and 35% in conflict-hit South Sudan.

Introducing a new vaccine that requires multiple doses has presented logistical challenges, especially in rural areas where transportation and storage options are limited.

In Ghana, there was also resistance from a number of traditional and religious leaders, and politicians skeptical about the benefits, Yaidoo told Reuters.

But results talk, he said.

“Those who have had the vaccination, they give their testimonies on how their children are protected from severe malaria. So many of them are actually our ambassadors."

Cases of severe malaria among vaccinated children were 58% lower than among unvaccinated children in the year after they received the third dose across the countries that participated in the pilot, a study published in The Lancet medical journal in January found.

Health officials in Kenya and Malawi did not respond to Reuters’ questions about their vaccination programmes.

At least four more countries plan to introduce malaria vaccines before 2028, Gavi said.

Until this year, Gavi could subsidise 85% of the assessed need for shots in areas of medium and high malaria transmission, with governments contributing as little as $0.20 per dose.

It has now reduced its spending cap to 70% for areas that will be ordering shots for the first time, the documents show. It will also be asking all but the poorest governments to increase their contributions, which vary depending on the strength of their economies.

Details of how these changes will affect individual countries are being worked out, Gavi said.

Price cuts for the vaccines could help mitigate the aid cuts. GSK and its partner, India’s Bharat Biotech, said in June they would reduce the price of their shot to under $5 a dose by 2028, roughly half what it costs now. In November, Gavi and the U.N. children's agency announced a deal to pay 25% less for Serum’s vaccine, currently priced at around $4 per dose, within roughly a year.

GSK said the real-world data was encouraging, and it was working with Gavi on how to make the roll-out as effective as possible. It did not elaborate. The other companies did not respond to requests for comment.

At least three countries - Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast and Togo - have committed to covering some malaria vaccine needs themselves, Gordon said.

But Tanzania is struggling to plug funding gaps and will have to delay the start of its vaccination campaign, said Dr Samwel Lazaro, acting head of its malaria programme.

“Currently, the government is focused on ensuring the implementation of the most essential and life-saving services, such as the use of medicated bed nets,” Lazaro said.