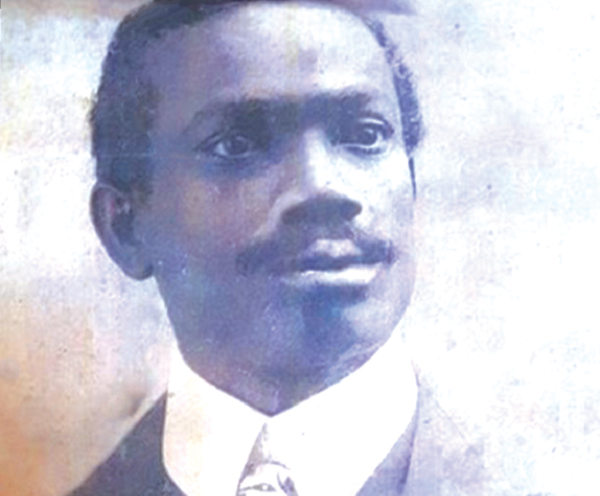

The sacrifices men make - A memorial to George Alfred Grant

In his twilight years, Mr George Alfred Grant, renowned merchant, political activist, and key founder of the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC), would occasionally be found in the company of former colleagues and friends at his home in Sekondi. However, most often, he could be seen leaning over his balcony, alone and in pensive mood. A true patriot who alongside others had committed time, energy and resources to their cause, Paa Grant was a man who, as we say in a modern parlance, had truly put his money where his mouth was.

As a granddaughter that never knew him, I have gleaned from my 93 year-old mother Sarah, and other family recollections, that Papa was a truly humble, hardworking and principled gentleman.

Interestingly, he was the grandson of a Scotsman who was one of the earliest merchant princes of the Gold Coast and a Legislative Council member from 1863 to 1873. No princely fortunes were earned here, though. Grant started his career in 1895, as a messenger with Messrs. C.W. Alexander & Company, timber dealers and general merchants in Assini, Ivory Coast, where his own father had sent him towork. However, Grant excelled even at this: from a paltry monthly salary of 15 shillings, he had by 1914 learned enough on the job to heed C.W. Alexander’s own advice to try out the business for himself.

Going through his paces of apprenticeship and service, Grant was a graduate of the school of hard knocks, eventually rising to become a well-known merchant with business connections overseas. Not only did heown shipping vessels, he was also recognized as an authority in the timber business, and was consulted on his trade by governments and foreign businessmen alike.

Papa was no big desk executive. Here was a man who spent much time in Dunkwa, Sefwi-Wiawso and other deep forest locations with his best friends during long days at work, and in the evenings play on the draughts board. These were the labourers with whom he felt most comfortable.

By his trade, Grant was in pole position to witness the unfair practices that both the local players in business and the indigenous workforce suffered at the hands of the colonial authorities.

Funding Nkrumah’s return

With his growing frustration and preoccupation with matters anti-colonial, any harmonious backslapping with associates in the colonial government would soon turn sour. Calls for a new political direction were gathering intensity, and a historic evening at Beach Crescent House with Dr J.B. Danquah set the UGCC ball rolling. Other members came on board and the “Big Six” would eventually come to headline the new party whose goal was to achieve selfgovernment.

It is noteworthy that when the time came to appoint a new Secretary- General, Grant responded immediately to the recommendation made by Lawyer Ako Adjei, of Dr Kwame Nkrumah. With a gesture of complete trust, Grant went into his room to fetch money for the fare to repatriate a returnee of whom he knew little. Nowadays, we might be hesitant to emulate such spontaneity, lest it causes an investigation for fees! Yet, in their quest to facilitate the nowpresent reality of independence, Grant and the gentlemen of the UGCC around that table took the leap of faith to commit to a candidate on the spot, with only the mildest of reference checks.

So Nkrumah did return, and the rest is history.

Effects on his business

In time, Grant’s full-time business enterprise gave way somewhat to his avid pursuit of the political freedoms and civil liberties of his fellow citizens.

It is telling that the suffering visited on his business seemed to correspond directly with the intensity of UGCC activism. But Grant was determined to fight. So when his timber was suddenly no longer welcome on trains, he resorted to transporting his logs to the harbour by long vehicle. The simple reaction from the authorities was to prevent logs stamped ‘GG’, from boarding any ships at the harbor.

Then came further hits:

In 1946, RT Briscoe came from South Africa to understudy Father (George Grant). Father took him round to his concessions. They were working nicely when a law was passed banning round logs to UK. Briscoe and Father then decided to build their own sawmills.

Father built his sawmill at Kojokrom while Briscoe built his at Essikadu in Sekondi.

They applied for power to run their mills. Briscoe’s application was supplied, but George Grant’s application was delayed. Then the inevitable happened. A big rejection, forcing George Grant to resort to gas to run his sawmill.

So Papa really helped R.T Briscoe, whose company became renowned in Ghana. Although Briscoe was so grateful to Papa is it not ironic that Briscoe’s business thrived while that of Papa, a citizen of the Gold Coast, died soon after the struggle began?

On this 61st anniversary of his death on October 30, 1956, it is salutary to consider the evidence that in the deep pre-independence era, we had such noble persons fighting not only for freedoms but also for the fair treatment of the country’s local content in business. It bears repeating that the vestiges of these elements of colonial rule, continue to be the bane of many a local entrepreneur in our modern-day business world. It is to be lamented, for example, that it took the discovery of oil in commercial quantities in 2007 for Ghana to pursue a local content law that would cast this policy in stone.

It is therefore heartwarming that Women, the Youth and the Disabled are to be counted among the lucky 30 per cent who will be eligible for 70 per cent of government contracts given to local contractors under the laudable procurement policy initiatives of the NPP Government.

Grant died from the effects of a stroke months before independence.

Had he survived longer, life would have certainly been sweeter for him, having tasted such bitterness. I am minded to wonder what was going through his mind on that balcony and whether he thought it had been worth all the sacrifices.