Ghanaians, I would like to believe and agree that corruption is something governments must fight.

Over nine rounds of the Afrobarometer survey, here is how they have answered the question “In your opinion, what are the most important problems facing this country that the government should address?” regarding corruption.

Out of the total number of important problems, here is how corruption ranked – 16th out of 25 (2002); 15th out of 29 (2005); 18th out of 35 (2008); 11th of 35 (2012); 9th out of 34 (2014); 5th out of 31 (2017); 7th out of 30 (2019); 6th out of 31 (2022) and 9th out of 32(2024).

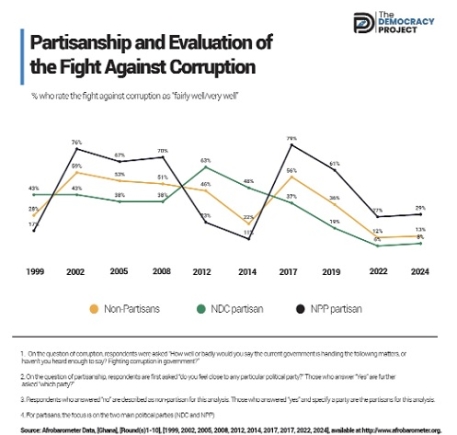

Ghanaians again have a sense of how well they perceive a given government in fighting corruption. Over 10 rounds of the Afrobarometer survey, here are the percentages of Ghanaians who have rated the fight against corruption as “fairly well/very well”- 31 per cent (1999); 63 per cent (2002); 55 per cent (2004); 56 per cent (2008); 43 per cent (2012); 25 per cent (2014); 60 per cent (2017); 39 per cent (2019); 14 per cent (2022); and 16 per cent (2024).

In essence, we agree that we must fight corruption. Furthermore, our dissatisfaction with how well different governments have fought corruption is very clear. However, we appear to face a twin dilemma on how to fight corruption – one institutional and the other political.

Institutional dilemma

There was a period during which we argued that the Attorney General’s Office was not the strongest institutional answer to fighting corruption in government for various reasons.

First, because he or she is a political appointee of a government in power, there may be no incentive to pursue in-regime accountability.

That lack of independence meant that only post-regime accountability, after a turnover election, becomes the only viable option.

But that turns into a partisan cry of witch-hunting and political vendetta against a party.

We elect Presidents who promise to fight corruption, but we occasionally also question their political willingness to hold their political appointees accountable for alleged acts of corruption.

Our dissatisfaction with how certain allegations were handled led to the adoption of the phrase “clearing agent” as part of our political lexicon.

A new office was added to our anti-corruption infrastructure to resolve the institutional limitations facing an Attorney General or a sitting President.

This office was designed to be independent, even though the legislation that brought it into force made the President the appointing authority for the special prosecutor, deputy special prosecutor and other staff in the office as he or she may deem appropriate.

After seven years in operation, as Ghanaians debate the resource investment in the office and the returns so far, it is also subjected to some of the same witch-hunting and politically ill-motivated narratives.

Partisan environment

Our partisan politics further exacerbate these institutional dilemmas. In this environment, the most legitimate pursuit of accountability degenerates into a partisan fight.

Even a basic demand for satisfactory answers appears unacceptable. What I observe as a key underlying factor in these partisan fights is a lack of trust in our institutions.

What I find intriguing, though, is the changing nature of trust in these institutions when in power versus when in opposition.

My question is, if our anti-corruption institutions, in addition to their limitations, are always vulnerable to partisan narratives, where does that leave us in the fight against corruption?

What is the institutional answer to our dilemma?

Which institution and their officials are partisans willing to trust?

Is there a way to arrive at a partisan consensus?

If we cannot reach this consensus, we might as well give up the fight against corruption.

Where do we go from here?

I do not hold brief for institutions that act contrary to the law and do not operate in a fair way that reflects restraint in the use of administrative discretion.

I agree that there are occasions where the discretion exercised by our public administrators raises eyebrows.

It is the reason I often argue for institutional rules that are highly prescriptive and narrow the discretionary latitude of our public administrators.

I cannot make excuses for all our partisan narratives, some of which, in my humble opinion, are unjustified.

I sincerely believe that a certain amount of restraint must be exercised when tempted to subject all actions and decisions of anti-corruption institutions to a political test.

In the absence of restraint, all institutional actions and decisions will be viewed with suspicion when they do not pass our partisan political test.

If we are truly committed to winning the fight against corruption, we must take a second look at how our partisan politics may be getting in the way, even if unintended.

The writer is the Project Director, Democracy Project.