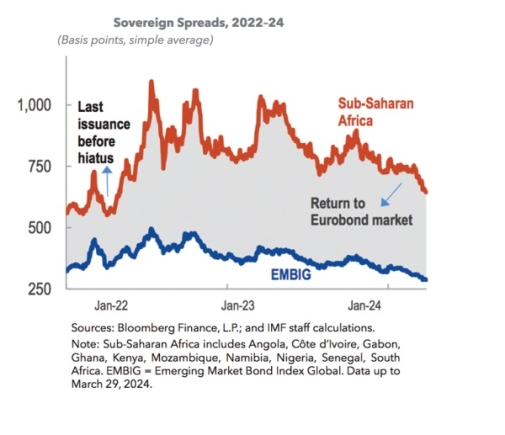

After four turbulent years, sub-Saharan Africa appears finally on the mend. With the easing of global financial conditions, Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, and Kenya issued Eurobonds earlier this year, ending a two year hiatus from international markets for the region.

Public debt ratios have broadly stabilized, and some capital flows are making a tentative comeback. The overall regional outlook is gradually improving, with economic activity tepidly picking up. Growth will rise from 3.4 percent in 2023 to 3.8 percent in 2024, with nearly two thirds of countries anticipating higher growth.

Economic recovery is expected to continue beyond this year, with growth projected to reach 4.0 percent in 2025. In parallel, median inflation has almost halved from nearly 10 percent in November 2022 to about 6 percent in February 2024.

However, not all is rosy, and the funding squeeze continues. The region’s governments continue to grapple with financing shortages, high borrowing costs, and rollover risks amid persistently low domestic resource mobilization. Significant debt repayments are looming this year and next.

The financing challenges are forcing countries to cut essential public spending and redirect development funds to debt service, thereby endangering growth prospects for future generations.

The funding squeeze partly reflects a reduction in the region’s traditional funding sources, particularly Official Development Assistance.

External financing

Gross external financing needs for low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa are estimated to exceed $70 billion annually (6 percent of GDP) over the next four years.

As concessional sources have become scarcer, governments are seeking alternative financing options, which are typically associated with higher charges, less transparency, and shorter maturities.

The cost of borrowing—both domestic and external—has increased and continues to be elevated for many. In 2023, government interest payments took up 12 percent of its revenues (excluding grants) for the median sub-Saharan African country, more than doubling from a decade ago.

The private sector has also started to feel the pinch from higher interest rates. Risks to the outlook remain tilted to the downside.

The region continues to be more vulnerable to global shocks, particularly from weaker external demand and elevated geopolitical risks.

Moreover, countries in sub-Saharan Africa face rising political instability and frequent climate shocks.

The region faces a critical year with 18 national elections in 2024. Similarly, climate shocks are becoming more frequent and widespread, including droughts of unparalleled severity.

Amid current financing constraints and cascading shocks, the international community needs to play a more active role in assisting the region. In addition, three policy priorities can help countries adapt to these challenges: improved public finances focused on revenue mobilization is still the first line of defense against a world of higher borrowing costs and narrowing funding options.

Impact of fiscal consolidation

But top priority should be given to minimizing the impact of fiscal consolidation on lives and livelihoods. On the financing side, there is still a pressing need for concessional funding. Monetary policy should remain focused on ensuring price stability.

As inflation eases, more countries will have space to cut interest rates. Enhanced coordination between fiscal, monetary, and exchange rate policies is crucial.

Implementing structural reforms such as expediting trade integration and improving the business environment to attract more foreign direct investments could diversify funding sources and the economy.

Sub-Saharan African countries will need more support from the international community, with multilateral and regional development banks potentially exploring options to further leverage their balance sheets to support a more inclusive, sustainable, and prosperous future.