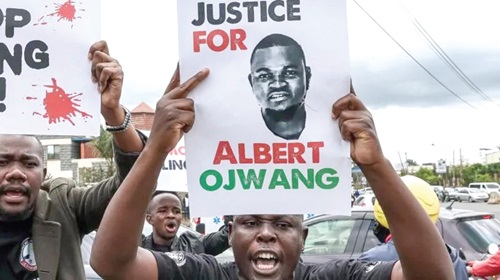

The death of Kenyan blogger, Albert Ojwang, in police custody has raised concerns about brutalities by security forces, especially the police, against civilians here in Africa.

Ojwang, 31, according to various international media reports, was arrested on Friday, June 6, 2025, in his western hometown of Homa Bay after being accused by Kenya’s Deputy Police Chief, Eliud Lagat, of tarnishing his name on the social media platform X.

Two days later, Ojwang was dead.

The initial report by the police suggested that Ojwang died of self-inflicted wounds, with the claim that he sustained head injuries after hitting his head against a cell wall.

He was found unconscious during a routine inspection of the cells and was taken to hospital, where he was pronounced dead on arrival.

However, the police were compelled to change the narrative after a post-mortem report by state pathologist Bernard Midia contradicted their claim.

The report said he was hit on the head and that his death was likely caused by assault.

"The cause of death is very clear; head injury, neck compression and other injuries spread all over the body that are pointing towards assault," state pathologist Bernard Midia said, the BBC reported.

Three police officers, namely Kiprotich, Talaam James Mukhwana and Peter Kimani, have since been charged along with three civilians in the case.

Eliud Lagat has also stepped down for investigations to go on.

Ojwang’s death sparked days of protests in Kenya, with rights groups calling for the police to be held accountable for his death.

Africa

Ojwang is not the first to have died in police custody under such circumstances. In fact, across the continent, many such incidents have been recorded. People have suffered various forms of police brutality during peaceful demonstrations, protests, arrests and incarceration.

In Nigeria in 2020, the Nigerian army and police killed at least 12 peaceful protesters at two locations in Lagos during the #EndSars protest.

According to Amnesty International, witnesses at the Lekki protest ground said soldiers arrived at about 6.45 p.m. local time and opened fire on protesters without warning.

In what came to be known as the Marikana Massacre in South Africa in 2012, mine workers at the Lonmin platinum mine in Marikana went on strike demanding higher wages.

On August 16, the police were reported to have opened fire on striking miners.

Up to 34 miners were killed, and over 70 were injured. It was described as one of the worst incidents of police violence since apartheid.

During the 2021 election campaign in Uganda, security forces were reported to have violently cracked down on opposition candidate Bobi Wine and his supporters.

In November 2020, at least 54 people were killed during protests following Bobi Wine’s arrest.

There were reports of torture, disappearances, and the killing of opposition supporters.

Human Rights Watch reported that in Zimbabwe, security forces used excessive lethal force to crush nationwide protests in mid-January 2019 following President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s sudden announcement of a fuel price increase of 150 per cent, which resulted in three days of demonstrations throughout Zimbabwe.

The body reported that the security forces fired live ammunition, killing 17 people, and raped at least 17 women.

Coming home to Ghana, examples abound of highhandedness by police and other security services against civilians.

A few of such incidents are the 2021 killings in Ejura, where the police and military officers shot two persons to death after they opened fire on unarmed protesters demonstrating over the killing of social activist Ibrahim Mohammed.

In 2020, security forces shot into a crowd during the 2020 general election collation process in Techiman South which led to the death of two persons with many others getting injured.

These examples show a pattern of systemic abuse, lack of accountability, and often, state-sponsored violence against civilians. In many cases, investigations are slow or inconclusive, while justice is rare.

Clearly, police brutalities occur in Africa just as they do in other parts of the world, but the implications this has on the relationship between the police and the public are something we need to worry about.

Implications

In their day-to-day work, the police thrive on information from the public to be able to carry out investigations, make an arrest or even prevent a security threat from happening.

If the relationship between the police and the public is broken because of their high-handedness in handling cases involving the public, how can the police achieve their mandate?

Police brutality against civilians can lead to a loss of trust in the police, and once this happens, people would be reluctant to go to the police to seek help or volunteer information, which could help in investigations. People are less likely to also report crimes, provide tips, or serve as witnesses when they don’t trust the police.

This hampers investigations and weakens overall law enforcement efforts.

This can go a long way to make the work of the police in maintaining law, order and protecting citizens difficult.

When members of the public witness or experience police brutality, they begin to see the police not as protectors but as threats.

Police brutalities create a climate of fear, where people are afraid to interact with the police, even in emergencies.

Incidents of police brutality can spark further protests, riots and public outrage.

What happened a few weeks ago in Kenya, when the people stepped up protests against police brutality as they marked the first anniversary of protests against increases in taxes, is a typical example.

The protests became a platform for the public to voice out their frustrations and anger against the injustices being meted out to them.

Police reputation damages

It is important to point out that police brutality affects the reputation of the entire police institution, as they can be viewed negatively, making it harder for the police to build relationships with the community.

"It is bad, really bad. Most people avoid the police intentionally. Sadly, one has to avoid the very people who should provide security," Chineye, a banker in Nigeria's commercial capital, Lagos, who was quoted by DW, said.

Police brutality often leads to lawsuits, settlements and court cases against officers or departments.

These legal battles can really cost cities and drain public resources that could otherwise be used for community development or crime prevention.

Way forward

Police brutality on civilians does not augur well for any of the parties concerned.

Many of these brutalities occurred as a result of poor handling of demonstrators or protestors and a lack of emotional control.

Training on how to control such crowds needs to be enhanced for personnel in the service.

The police administration also needs to send a strong signal to its personnel that abuse will not be tolerated, and that those who are culpable would be penalised severely.

Indeed, it is important that personnel found culpable for brutalising civilians are punished to serve as examples.

Just like personnel of the service, independent organisations need to educate the public on the channels to use to seek redress for their grievances.

In these days of several demonstrations and protests, they also need to educate civilians on their limits when protesting against or for something.

After all, often they are the ones who suffer most when protests or demonstrations escalate.