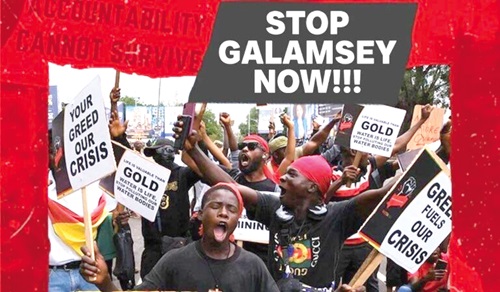

Illegal small-scale mining, popularly known in Ghana as galamsey, has become one of the most destructive environmental crises of the 21st century.

What began decades ago as a survival activity for rural youth has evolved into an extensive, highly organised network that threatens the nation’s water bodies, forests and long-term economic stability.

From the Ankobra and Pra rivers to the Birim and Offin basins, the scars of galamsey are now visible from space. Muddy waters, deforested hills and once-thriving ecosystems reduced to barren landscapes.

Dangers

The environmental consequences are profound. Galamsey operations use mercury and other toxic chemicals to extract gold, polluting rivers that serve as drinking water sources for millions.

The Ghana Water Company has repeatedly warned that several treatment plants risk closure because of siltation and contamination.

Aquatic life has been destroyed, biodiversity has declined, and farmers have lost fertile lands to mining pits.

The future of Ghana’s major cash crop, cocoa, is seriously threatened.

Many cocoa farms have been lost to galamsey activities, and the quality of cocoa beans is at risk.

The wider ecosystem, forests that regulate rainfall, rivers that sustain agriculture and wetlands that protect against flooding, is collapsing under the pressure of unregulated mining.

Controlling the menace

Yet, despite the scale of devastation and years of public outrage, successive governments have struggled to control the menace.

The failure has been less about a lack of laws and more about the politicisation of enforcement.

Governments often launch highly publicised “wars on galamsey”, deploying soldiers and police for dramatic crackdowns, only for illegal mining to resurface weeks later.

Political interference and vested interests have undermined consistency and accountability. Local authorities, who should be at the frontline of enforcement, are too often caught between enforcing the law and protecting political loyalties.

Moreover, most anti-galamsey strategies have followed a top-down model, with decisions imposed from Accra rather than developed in partnership with affected communities.

The people who live beside the rivers and forests are rarely engaged in decision-making, even though they are the most affected and could serve as powerful watchdogs.

Enforcement has also been measured by inputs, how many excavators were seized or how many arrests were made, rather than tangible outcomes like cleaner water, restored forests or rehabilitated land.

Politicised enforcement

To move forward, Ghana must abandon this cycle of politicised enforcement and adopt a comprehensive, multi-pronged approach grounded in transparency, institutional accountability and local participation.

The fight against galamsey cannot be won through military might alone. It requires systemic reform and a shift towards measurable, community-driven outcomes.

A new framework for tackling galamsey should begin with transparency, data reporting and judicial reform.

The Ghana Water Company Limited(GCWL) should be mandated to publish daily water quality reports for all treatment stations, making data publicly accessible and empowering citizens to hold authorities accountable.

The government should introduce a monthly “State of Water Quality Report”, modelled on the transparency of COVID-19 briefings, focusing on key contaminants such as mercury and aluminium. These reports would keep environmental health at the centre of public debate and make it easier to track progress or the lack thereof.

Evaluation

Accountability must also extend to the highest levels of government.

Ministries and agencies should be evaluated based on outcomes, such as visible improvements in water clarity and forest regeneration, rather than operational statistics.

The Police Service should publish weekly arrest reports distinguishing between high-profile financiers and on-the-ground operators, while the Attorney General’s office should release updates on prosecutions.

Establishing specialised courts or tribunals to handle illegal mining cases would ensure faster, more consistent justice and deter impunity.

Institutional reform and enforcement must focus on dismantling the networks that fund and protect illegal operations.

Metropolitan, Municipal and District Chief Executives in mining-endemic areas should be assessed through clear key performance indicators, with dismissal and investigation as consequences for failure and rewarded based on success.

Enforcement must target financiers, equipment suppliers and kingpins; the real architects of galamsey, rather than only the labourers at the bottom. Introducing tighter regulations for heavy machinery and tracking gold through blockchain or digital registration could help choke the supply chain that enables illegal trade.

However, enforcement alone cannot solve a problem rooted in poverty and unemployment.

Many young people engage in galamsey not out of greed, but desperation.

The government must, therefore, invest in socio-economic solutions and formalisation.

Sustainable livelihoods, through agriculture, vocational training, eco-tourism and small-scale industries, can provide viable alternatives.

Properly regulated Small-Scale Mining Cooperatives should replace the chaotic informal sector, operating within designated zones and trained in mercury-free, environmentally sound methods.

Recovery plan

Finally, environmental recovery and technology must become central pillars of the new anti-galamsey agenda.

Ghana should launch a dedicated 24-month Catchment Recovery Plan to restore degraded riverbanks, desilt reservoirs, and replant vegetation.

Critical water bodies and forest reserves should be declared security zones to shield them from encroachment.

Modern technology, satellite monitoring, drones and real-time data analytics can help authorities detect and dismantle illegal operations swiftly.

The fight against galamsey is not just an environmental battle, it is a test of governance, integrity and national will.

Ghana must transition from rhetoric to results, from politicisation to partnership and from reactive enforcement to measurable, transparent progress.

Only by empowering communities, holding institutions accountable and restoring the natural environment can the nation protect its rivers, forests and future generations.

The writer is a political scientist.